Eye For Film >> Movies >> Adrianne & The Castle (2024) Film Review

Adrianne & The Castle

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Every now and again, photos circulate on social media because somebody has come across a house for sale which is decorated in such an extreme, over the top style that it makes people’s jaws drop. Who would live in a house like this? More than one person, usually, because they tend to be big – and that’s where things get interesting. How likely is it that somebody with such unusual tastes would happen to find another who shared them so completely? It’s commonplace to mock the houses and their imagined former residents, but to achieve that, well, it must be true love.

“It’s a brave thing people do when they fall in love,” remarks Alan St-George. “It’s going to hurt. Somebody’s going to get badly hurt.”

Alan was just 13-years-old, riding the bus home, when he saw Adrianne on the sidewalk. She took his breath away, and he spent the next several years wooing her, finally winning her over, the only love he has ever known. They married despite their families’ disapproval, accepting estrangement from them. When she confessed to not liking the house they had moved into, he told her that he was ready to change it in any way she wanted, and put all his skills as an artist and craftsman into doing so, never taking on another commission again. 45 years later, Haven Crest is their castle and a still-evolving monument to everything she gave him, but she is gone, snatched away by cancer. This documentary is part of the process through which he is trying to mend his broken heart.

It’s a metatextual, experimental film, exploring process throughout. There are reconstructions of key moments in Alan and Adrianne’s story, and he’s involved in the casting process, which gradually changes the way he thinks about the relationship and his grief. This engagement with actors and crew members is part of his larger process of engaging with the world as an adult, having spent most of his life either inside the castle or travelling around in Adrianne’s wake. in that time he has run a successful business, something he stumbled into unexpectedly, but he has had very little real connection with other people. Whilst viewers might gape at the fantasy world he has created, his face acquires a similar expression when he’s describing a first trip to Walmart.

Though she’s gone, Adrianne’s presence is everywhere. He walks us through the room where her diaphanous gowns still hang. One room has become a shrine to her, its various sculptures adorned with fresh flowers. We see her in old film footage, a large woman with a still larger personality, always focused on adventure, smiling and laughing, always certain of herself. Big hair and vivid make-up. He remembers her telling him “It’s never too late to have a good childhood.”

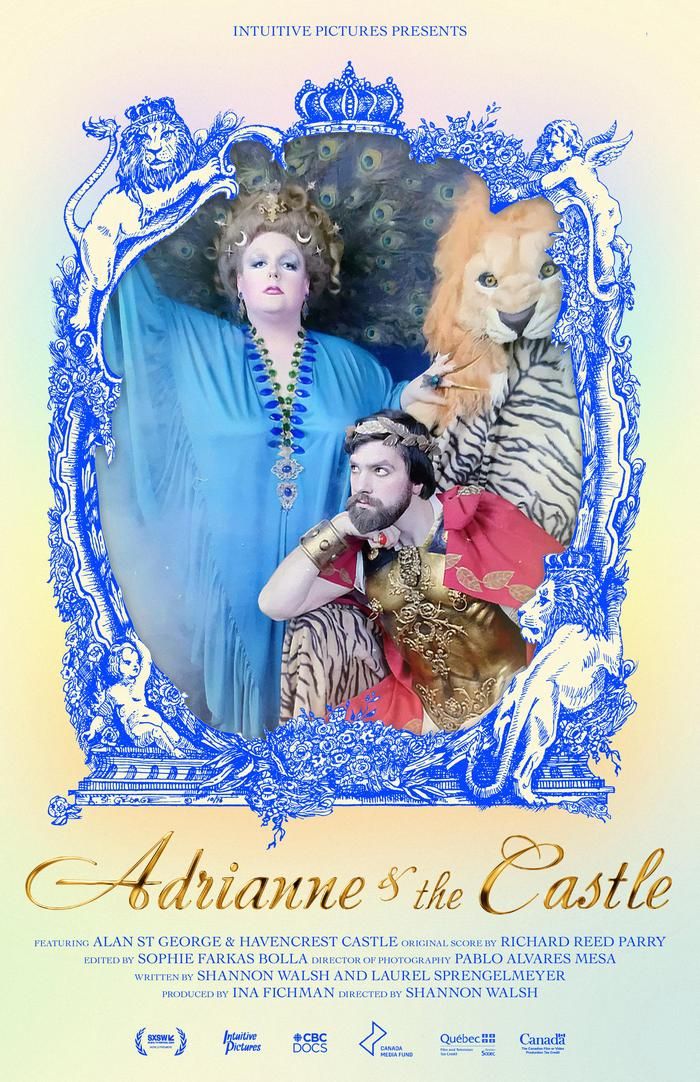

There are portraits of them throughout the house, in numerous styles, some more successfully imitated than others. The effect is sometimes comical, but true intimacy often looks absurd from the outside. He paints them as classical figures, reimagining their love through a variety of narratives. Sometimes she is Aphrodite, sometimes a medieval queen. A ceiling rosette depicts the two of them relaxing in a garden; she is twice his size and he is snuggled against her hip. In her doll room is a painting she did herself, of her beloved dog, Cartier. Beyond the dresses she designed, we don’t see many other examples of her creative work. He makes art, he explains. She was art.

It all sits rather awkwardly in the context of the wider world. The gaps are too obvious. Gilded ceilings don’t look right because they’re too low. Period-influenced rooms have colours which are just slightly off, clearly a product of fantasy rather than historical knowledge, and this tips their opulence further in the direction of New World vulgarity. That said, the whole of it is elevated by the genuine feeling that has gone into its creation, and one hopes that, as he reaches out further into the world beyond its walls, Alan never loses sight of that. It could be seen as tragic that he should still devote himself so completely to a dead woman, and yet, as he engages with the making of the film, he finds new ways of experiencing her love in the present moment. Films about grief are very valuable just now, given the scale of loss caused by Covid, and this aspect of Adrianne & The Castle will speak to many people. There are times when fantasy can make a vital contribution to real life.

Screened as part of the 2024 Fantasia International Film Festival, this is a film that celebrates the value of imagination, of life lived absolutely on one’s own terms. You’ll never look at those strange houses in the same way again.

Reviewed on: 21 Jul 2024