Eye For Film >> Movies >> Another Woman (1988) Film Review

Another Woman

Reviewed by: James Benefield

The stereotype of Woody Allen is a handwringing, therapy-addicted New Yorker with a string of failed relationships under his belt and a lot to say about them. Another Woman, one of his more overlooked films, sees its central character somehow justifying why all this is a good thing.

This is Marion Post (Gena Rowlands), a philosophy lecturer living in New York. After being granted study leave to write a new book, and thus spending an unprecedented amount of time at home, she soon finds out that the apartment down the corridor is used as a psychiatrist's office. She can also, through the walls, hear everything the patients talk about. Although initially blocking up the noise coming through a floor-level grate with some cushions, she soon becomes intrigued by one patient in particular. It's Mia Farrow's Hope, who is on the brink of ending her relationship and, also, thinking about suicide.

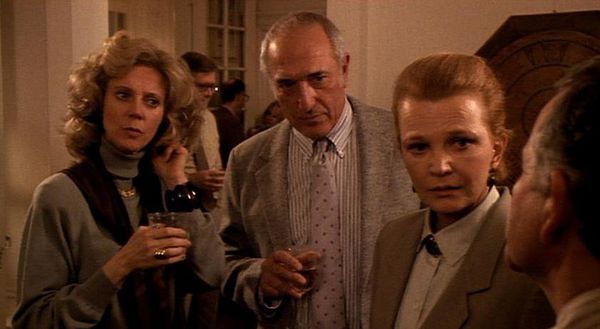

This eavesdropping – apparently unusual for Marion – doesn't come from nothing. After a rather traumatic party in which intimate secrets from two of her best friends are revealed, and the ex-partner of her husband comes to visit, she starts thinking about her own sex life and relationship. And it's not necessarily a pretty thing. Turns out she needs, if not some serious therapy, some time to consider what is important to her. She's spent too long bottling her problems up, and they're all about to come out.

Not since Hitchcock's Vertigo has a director's justification for his own obsessions been so rewarding. Firstly, you do question why Allen hadn't worked with Gena Rowlands before (although it's clear why he hasn't done so since – Another Woman is one of the Woodman's last gasps at world-class filmmaking). Rowlands is the perfect fit for the material – emotional anguish is this woman's forte as she has proved in many a John Cassavetes movie. This anguish is a controlled, almost beautiful, thing painted in a whole paintbox of colours.

Secondly, the movie never thrusts its messages down our throats. Self-justification or not, Allen never moralizes or casts judgements on his characters. Apart from Ian Holm's husband – whose liminality and barely sketched character eventually does demonise him – we're treated to characters' crimes and triumphs, which are, at times, mutually exclusive things.

With a supporting cast which includes Gene Hackman delivering a uncharacteristically understated performance, this is a film which is both thoughtful and surprising. And for a man who, not even half way through his directorial career, was already being dismissed as a one trick pony, this is a triumph.

Reviewed on: 18 Dec 2010