Eye For Film >> Movies >> Antrum (2018) Film Review

Antrum

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

As a film critic, one is, from time to time, offered various bribes and subjected to various forms of pressure in attempts to elicit positive reviews. It's a rare film, however, which implies that critics who so much as think about giving bad reviews might die as a result.

The idea behind this film is that it's a documentary commenting on and then presenting a film made in the Seventies which is believed to be cursed. In the preamble, we are told about a cinema that supposedly burned down in Budapest whilst screening it, and about various ill-fated film festival organisers. This is a nicely balanced piece of work which provides just enough scary suggestions to hint at something real or feed a conspiracy theory, but not so many as to be conclusive. It will succeed in setting many viewers' nerves on edge before the feature presentation: what is supposedly a recovered copy of the cursed film itself.

All is not as it seems here, and if you know a bit of Russian, catch the minor slips in the set decoration or simply know your film history (the disclaimer card delightfully recalls promotional materials attendant to the original release of Roger Corman's The Pit And The Pendulum), you'll quickly come to understand the game being played. There's no real disappointment about that, however. Whether one approaches Antrum with trepidation or amusement, it's a very good film, and directors David Amito and Michael Laicini really know their stuff.

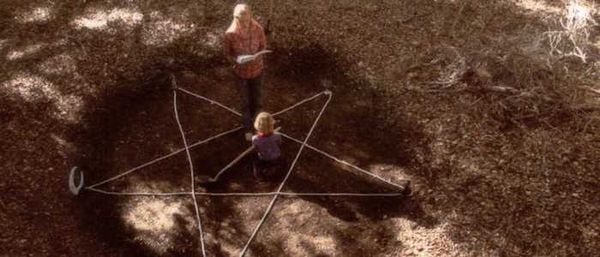

The story follows teenager Oralee (Nicole Tompkins) and her little brother Nathan (Rowan Smyth) as they visit a forest known locally as a suicide hotspot and rumoured to be the place where the Devil hit the Earth when cast out of Heaven. Family dog Maxine has recently died and Nathan is haunted by nightmares, an ill-considered remark by his mother having convinced him that she's gone to Hell. Oralee's plan is to help him overcome his grief through a fabricated ritual in which they will dig a hole and undertake an imaginary journey to Hell to free her soul. The problem is that as their ritual progresses, odd things start to happen which imply that the ritual might have some real meaning after all. Material forces also emerge within the forest to present a potential threat, and the pair witness a number of incidents that most adults, never mind children, would be better off never seeing. Changed by her experiences, Oralee begins to lose control of the situation. What started as a form of play could have deadly consequences.

The meta narrative is well paired with this internal one as Antrum questions the impact of the imaginary on human psychology and thus, indirectly, on the physical world. Though essentially about the power of storytelling, it also uses tricks both auditory and visual of the type that several filmmakers were experimenting with in the Seventies. The epilogue - back in documentary format - explains a few of these directly, but this only adds to the fascination of the piece.

Smyth is a real find, perfectly capturing the style of the time whilst winning the sympathy of his audience. His performance feels fresh and yet emotionally charged; we are easily absorbed into his world, able to understand his priorities and how they differ from those of the adults around him. Tompkins comes across as just a little too human for a Seventies teenage heroine, more self-aware and lacking that particular form of object status that would then have come from a director's belief in her helplessness, but this in itself raises interesting questions, not least around the ethics of treating a young actress that way today. She's otherwise good, just very slightly out of place. The pair have good chemistry, evoking a strong bond which makes it easy to accept the lengths that Oralee would go to to protect the boy.

There's superb technical work here all round. Amito and Laicini are never afraid to take things slowly, trusting viewers to stay with them as the tension develops at a natural pace. Alicia Fricker's score is a delight and Maksymilian Milczarczyk does wonderful work recreating the look of the period, even down to the damage one would expect such a film to have suffered over time (with none of the tedious scratching and crackling typically used to that end). The result is wholly absorbing, its narrative structure more like poetry than prose. The directors can't resist adding in a series of smaller mysteries and puzzles but, again, this is in keeping with the era, and it never gets in the way of experiencing the film directly. It will likely resulted in devoted fans watching over and over again.

Sometimes reminiscent of the early work of George Romero, this is a film out of time, an essay in style with all the surrounding structure placed at its service. On the evidence it is unlikely to send you to your death, but there's a genuine creepiness about it, and it will haunt you.

Reviewed on: 20 Oct 2020