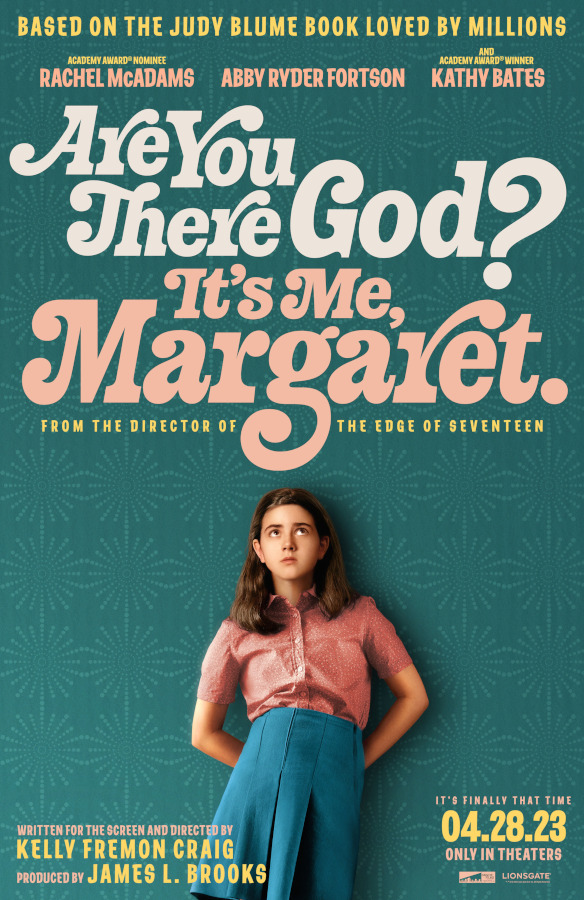

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (2023) Film Review

Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

For girls growing up in the latter part of the Twentieth Century, no author carried quite as much influence as Judy Blume. That had a lot to do with the novel on which this film is based. First published in 1970, it broke new ground in the frankness with which it discussed the bodily changes of adolescence as many girls experience them, and for this reason it was enormously important to many readers. Just as its heroine, the titular Margaret, finds a conversation partner in God, it was itself a companion to those who felt unable to discuss all of their insecurities elsewhere.

No doubt mindful that it could do harm if handled poorly, Blume hesitated for a long time before consenting to let it be adapted for the screen. This version sticks closely to both the text and the tone of her work, and seems to have hit the same sweet spot for much of its audience. It has nostalgic appeal to those who loved the book when it was new, and, though the story has thankfully not been shifted into the present day, it seems to be winning over a new generation of fans. That matters because challenges to the book have sadly increased with time, and in an era when girls’ right to information about their bodies is under attack in parts of the US, it remains a lifeline.

To be clear, it’s not just the body talk that makes some people uncomfortable. It’s also the exploration of religion. Margaret’s mother is Christian, her father Jewish, and as such they have agreed to let her make up her own mind about how she relates to God. Both have assumed that she will still believe in God, and the film, like the book, is cautious in this regard, prompting questions but not wanting to alienate an essentially conventional audience. Likewise, almost everybody is white and straight and physically healthy, and there is an expectation that they will happily follow a prescribed path through life. As such, it’s a story with which many other girls will find no point of connection at all, a portrait of ‘normalcy’ which shores up the illusion that that’s all there is. It is very much a product of its (original) time.

Within that space, the white feminist battles of the era are being fought. We begin as the family settles into a new home, a traumatic experience for Margaret (here played by Abby Ryder Fortson) as it is for most children who find themselves uprooted and torn away from family and friends. There is also a more subtly expressed form of trauma for her mother, Barbara (Rachel McAdams), who gives up a job as an art teacher and finds herself co-opted by the local Stepford set. Her father, Herb (Benny Safdie) is present only on the periphery of her life, concerned with work and finances of which she has little understanding, but his mother, Sylvia (Kathy Bates, stealing the show as usual) encourages Margaret’s independence at the same time as she tries to draw her into Judaism.

Margaret has a bit of luck in her new neighbourhood, quickly being adopted by popular girl Nancy (Elle Graham), who seems to recognise how malleable she will be due to her lack of connections and uses her to increase her own influence, inducting her into a clique. Excited by this opportunity and eager to fit in, Margaret quickly shares in the spreading of malicious gossip about classmate Laura (Isol Young), and it’s interesting to see bullying explored from this side, encouraging young viewers to question their own behaviours rather than simply sympathising with victims.

Margaret’s credulity makes her vulnerable too, but in different ways. She is only just beginning to recognise that other people might not be as sophisticated or confident as they appear. Prompted by a school assignment, she also develops a curiosity about aspects of her family structure which she has previously taken for granted. Here the film builds on the book, aided by its capable cast, to give us more idea of what the older characters are dealing with and the pain they have hidden in order to permit her to grow up as blissfully clueless as she is.

Ultimately, it’s all very wholesome. Margaret reaps rewards without having to work very hard for them, and the lessons she learns along the way don’t cost her much – but this is reality for some young people. What the film does well is to establish that, in the absence of larger problems, anxiety is refocused on smaller ones. Bodily changes, or the absence thereof, are of particular concern. There is humour in this as well as misery, and the two are carefully balanced. A score by maestro Hans Zimmer manages the mood skillfully throughout.

As for God, His existence and preferences seem to depend on what Margaret feels He’s doing for her rather than on any real developing philosophy, and one gets the impression that this might well be the case for the rest of her life, but the device of prayer provides a convenient way to break the fourth wall. Although her behaviour sometimes feels forced or over-written, Margaret herself feels real, and if she’s the sort of person you relate to, you may well enjoy this film a good deal.

Reviewed on: 11 Feb 2024