Eye For Film >> Movies >> Bad Lieutenant (1992) Film Review

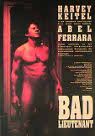

Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant was released in 1992 and, following the opening of Tarantino’s debut feature Reservoir Dogs by only a few weeks, it was the second film to announce the welcome return of Harvey Keitel as a leading man. Although both films were highly controversial, Tarantino’s film was the by far the more accessible - and consequently successful - of the two. Not only was it a genre pic (albeit an exuberantly inventive and original one); it was a stylishly executed, tightly wrought film, elevated by some smart dialogue and clever use of a hip, period soundtrack.

Bad Lieutenant, on the other hand, was (and is) a far less appealing and approachable piece of work. Largely set in the filthy backstreets of nocturnal New York, Ferrara’s film is an ugly, downbeat and virtually plotless character study-cum-contemporary religious parable. Examining the last days of a morally bankrupt cop, it features lengthy scenes of graphic drug-abuse, masturbation, rape and self-abasement, and is shot and directed with an emphasis on formal austerity. Sparse dialogue scenes in squalid apartments unfold as halting, inarticulate conversations and a wandering semi-structure - foregrounding incident and behaviour as opposed to story and performance - recall the somewhat ill-disciplined experimentation of Cassavetes.

Critics were, generally speaking, not impressed and, uncertain as to whether the film was exploitative art or an arty piece of exploitation, decided it was simply pretentious trash and wrote it off as a dead loss. Many were shocked by the relentlessly sordid subject matter, while others were repelled by what they perceived as Ferrara’s solipsistic determination to make everyone else wallow in his own moral dissolution. Almost all, however, agreed that it was one of the most inexcusably boring films of its year, and even those who found space to comment favourably on the extraordinary intensity of Keitel’s performance found little else worthy of merit or praise.

However, Ferrara’s bleak, uncompromising film has nevertheless gained a significant cult following over the course of the last 18 years and its critical reputation has also improved with sober reassessment. Subsequent releases by controversial European provocateurs such as Lars von Trier, Catherine Breillat and Gaspar Noé have raised the bar, and Ferrara’s formerly outrageous offences against good taste and propriety now appear unremarkable by comparison, thereby making attacks on the film’s alleged sensationalism largely irrelevant.

Keitel’s eponymous police Lieutenant (very few of the characters are named) is already a good way down the road to ruin when the film opens, and the first 20 or 30 minutes are given over to an episodic catalogue of his various crimes – he takes bribes; he attempts to steal narcotics from a murder scene; he sexually harasses young women; he consumes vast quantities of cocaine, crack, heroin and alcohol; he indulges in pitiful, maudlin orgies with whores, and he robs suspects he’s supposed to be arresting. (As a number of particularly frivolous critics pointed out at the time, we are never given to understand when he finds the time to do any actual policework.)

But of all his vices, it is his worsening gambling problem – itself a product of his loosening grip on reality – that presents the most immediate danger, and Ferrara uses radio and television coverage of the ongoing World Series as both an omnipresent backdrop of gathering threat and a means of imposing a loose seven-game structure on his narrative. In the absence of a strong, propulsive plotline, this shrewd decision gives the story a backbone even as it chronicles its protagonist’s exponentially escalating debts in the face of mob demands to pay up. When the Catholic Church offers a five-figure reward for information leading to the arrest of two local boys who raped a beautiful young nun, Keitel’s increasingly exasperated middle-man suggests the Lieutenant would do well to claim it if he wishes to avoid becoming part of a motorway.

Our hero is at first uninterested in the investigation, and even declares that the Church’s unusual offer of bounty is evidence only of their comparable indifference to the suffering of ordinary people. But as he deteriorates and his desperation increases, he comes to understand that an ability to simply recognise profanity and the desecration of purity is the only remaining evidence of his shredded moral sense; the only thing separating him from total debasement. He is drawn to the victim – initially out of prurient fascination, then later out of a desperate need for guidance – and offers to avenge her if she will only tell him who was responsible. But he is appalled to discover that in her piety she has forgiven her attackers and is refusing to identify them even to her Confessor. “But do you have the right, Sister?” he demands of her. “These guys could do this to other women. Other nuns. Other virgins. Do you have the right to let them go free?”

And yet in spite of these ethical objections, it is out of this crazily literalist notion of mercy, self-sacrifice and grace that the possibility of truly transformative redemption finally emerges. For Ferrara’s interest lies neither in practical deliverance nor in the conventional plot schematics of earthbound justice or vengeance. Instead, he’s preoccupied with the prospect of eternal salvation.

Is such a thing even achievable for someone so fundamentally corrupt? And if so, then by what means can a man so lost begin to claw his way back? In its exploration of these questions, there are strong echoes of the more overtly theological films of Martin Scorsese, in particular his adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation Of Christ. Both films examine weak men, tormented by self-doubt and self-loathing, struggling to come to grips with what they think is required of them by a silent and apparently indifferent god. Is the possibility of redemption real or illusory? And if it is real, then is it practically achievable or are our appetites so corrupted and our will so weak that defeat is inevitable and striving for it hopeless? As the Lieutenant’s emaciated heroin dealer (played by the film’s co-screenwriter, Zoe Lund) slurs about two-thirds of the way through the film: “Vampires are lucky. They can feed on others. We gotta eat away at ourselves until there’s nothing left… nothing but appetite.”

It is this process of autocannibalism that terrifies Ferrara and that he seems to want to arrest. What’s astonishing about his film is that in spite of its tacit endorsement of Lund’s view, as evidenced by the film’s unrelenting catalogue of depravity, he and Keitel nonetheless manage to make a plausible case for hope, albeit one that exacts a terrible personal cost.

That this queasy and improbable line of argument even holds water is a tribute to the sensitivity and passionate sincerity of Ferrara’s direction, and of the unwavering commitment evident in Keitel’s mesmerising central performance. One gets the strong impression that both men identify with their wretched creation because of his weakness rather than in spite of it, and are able to communicate their protective understanding through a simple appreciation of the character’s vulnerability and fragile humanity.

They seem to intuitively understand the tragic nature of his self-imposed torment and helplessness, and it is in no small part the tarnished dignity that Keitel brings to his role that prevents the film from degenerating into a long, self-indulgent whine of self-pity. Neither director nor star ever lose sight of a simple compassion that insists that no one, as long as they retain even the faintest glimmer of self-knowledge, is beyond hope. And if redemption and grace are possible for one who has fallen so far, then they are possible for us all.

Lars von Trier’s similarly controversial parable Breaking The Waves ended with the strong suggestion that only total submission of the self – to the point of embracing one’s own annihilation – can lead one to transcendent grace in a corrupt and fallen world. Ferrara, like Scorsese, would appear to concur. But he then takes the argument one step further, by suggesting that such self-sacrifice might allow one to vicariously assume responsibility for the sins of others.

On any number of levels this is pretty extreme and problematic stuff to say the least, particularly when transplanted from mythical Palestine into a contemporary Western setting, but it is precisely this dissonance between Judeo-Christian teaching and contemporary Western ethics that these religious directors are seeking to challenge and explore.

What’s most surprising, given the explicit devotional overtones of all three films, is not that they were considered controversial and offensive by secular critics, but that they were also attacked as blasphemous and profane by the pious. In fact, it would be more accurate (but still, I think, unfair) to accuse all three directors of unreconstructed fundamentalism, since they not only endorse the doctrine of atonement but, in taking it to its necessarily extreme conclusion, they test it to the destruction of its adherents. But in so doing, it becomes difficult to understand any of these films as a sadomasochistic celebration of suffering. They are, to the contrary, harrowing portraits of human beings engaged in an epic struggle to comprehend and transcend it, and it is in the unflinching demonstration of the awful consequences of human cruelty, weakness and pain, that the devastating personal cost of this philosophy is most powerfully apparent.

The implied challenge seems to be: is it worth it? Ferrara, von Trier and Scorsese provocatively argue is that it is. But the counter-argument is nonetheless there for all to see. For, as the tragic disintegration of Keitel’s wretched Lieutenant clearly demonstrates: if sin doesn’t destroy you, then faith will.

Writer's note: There have been two rather regrettable postscripts to this film since its release 18 years ago.

The first was the tragic death on 16 April 1999 of the film's co-screenwiter Zoe Lund of a heart attack following a long history of hard drug use. Lund (née Tamerlis) had also starred in director Abel Ferrara's third feature, Ms. 45 (aka Angel Of Vengeance) and appeared briefly in Bad Lieutenant as Keitel's heroin dealer and shooting partner. A sad and rather moving obituary by her estranged husband of ten years can be found here: zoelund.com/filmvid/SensesOfCinema/intro.html and a site dedicated to celebrating her erratic life and work can be found here: zoelund.com/

The second coda concerns the film's soundtrack. Ferrara originally used a punishing rap song entitled The Signifying Rapper, by Philadelphia rap artist and regular collaborator, Schoolly D, to score three key scenes, including the pivotal rape scene. Unfortunately, the track was backed by a facsimile of the guitar riff from Led Zeppelin's Kashmir, and when the band discovered this they threatened to sue unless the song was removed forthwith. It seems that even though Ferrara had a strong case (is it possible to copyright a riff?) they decided it would be too expensive to contest the case in court.

The original soundtrack has survived on American VHS tapes and the fullscreen Laserdisc pressing, but was absent from all subsequent DVD releases. There are unedited versions of Bad Lietenant floating about, and anyone interested in seeing it would be well-advised to try and get hold of one. Although only an ostensibly minor alteration, it nonetheless significantly alters the overall tone of the film.

Reviewed on: 29 Mar 2010