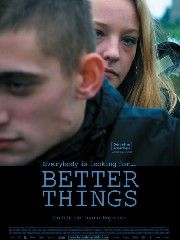

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Better Things (2008) Film Review

When you were little, did you ever hide under the bedclothes? Pretend everything outside didn’t exist? And as a teenager, did you hide your head in a pillow after a broken love affair? And now?

Duane Hopkins’ first feature is bleak yet intellectually satisfying. Bookended with nothingness. That emptiness – and the spaces in-between – are they brought on by loss? Or is it a basic condition?

Better Things uses narrative arcs but strips away storylines to make us examine such questions. Producing serious dramatic tension with such a bare palette is a remarkable achievement. Take Gail. She has agoraphobia. It keeps her indoors, escaping only within romantic fiction. Nan shares the same house. A world away. Mostly bedbound. Can their communication ever be more than, “a nice cup of tea?” Or Mr. and Mrs. Gladwin. Together for 60 years, much of it unspoken. Or teenagers filling a sense of isolation with hard drugs. Maybe dying. More loss. A bridge no longer crossable. Tess, dead in the opening scene with a needle still stuck in her arm. Lost souls on a sea of oblivion, each crying out with the tiniest of lights, the tiniest capacity for love. A still breath in the vacuum.

No trite ‘love is the answer’ will enable this film to fulfil any needs for feelgood fantasy. Surprising perhaps, when love is very much central to the film. Says its director, “It is of course what all of them are looking for, it is what they want and need, as we all do. But it is more complex than just finding it and receiving it, it is about whether you can accept it. Either because it seems impure or compromised from this person or you feel not deserving of it yourself. The emotion has a huge value to them but it does not mean that it can solve everything for them. It is not just love that they crave; it is security, safety, and validation of their own worth. They need to feel that they have a greater responsibility.”

A penetratingly realistic approach, combined with avant-garde technique in composition and structure, gives Better Things its weakness and strength. I cannot imagine it satisfying mainstream audiences, even before we come up against graphic drug use (and some of the actors are former users). I was feeling ready to dismiss it. But then it comes together so coherently. Hopkins is no dilettante parading style over substance. He picks a complex, abstract idea as his theme. He obsesses (in a good way) about theme over story. More mainstream filmmaking would parade its ‘themes’ yet coyly duck real concerns.

In that great film The Diving Bell And The Butterfly, for instance, a ‘theme’ of ‘being trapped’ is approached by comparing a quadriplegic, a Beirut hostage, and an old man with problems navigating stairs. We could feel some artistic elation at perceiving the ‘underlying message’. But in fact the audience was free to ignore such subtlety by concentrating on life-stories, beautiful photography, and enjoyable emotions overcoming extreme adversity. Such niceties play to the desire to be entertained without recognising the mundane misery of being trapped - much less the possibility of better things for most mortals.

“I’m interested in what the story represents,” says Hopkins. “The more story you remove, the more theme is left because the audience has to work harder.” And the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. As long as the director isn’t being deliberately obscure (and this one isn’t), there’s a sense of achievement and understanding which is a pay-off for the effort. Individual characters have limited relevance to our own lives. But the theme is usually more universal. By working on it we also make it something we own. And if Hopkins can go on to ‘even better things still’, then theatre-goers may be treated to his examination of other deep issues. Will this bold approach take wings as it did for Godard or will Hopkins remain welded to rural grunge?

Regarding the structure of the film, he says, “The drama in Better Things comes from a gradual build up of scenes that relate to and complement each other thematically and build an impression of an area, its inhabitants and their individual stories through these sequences.” As a setting, it also becomes the unifying element, where lives are probably shared even if not in the narrative. Better Things is set in the Cotswolds. This ‘Green and Pleasant Land’. The England most city-dwellers romanticise. The England where country-dwellers increasingly find themselves marginalised.

Isolation is cleverly emphasised with neat stylistic touches. An almost total absence of panning and tracking shots gives the impression of a gulf between each mise-en-scene. There is a lack of camera movement, just as subjects find it hard to move towards each other, physically and emotionally. The stillness, the inability to move forward, seems to overpower everything else. And, when two boys are driving in a fast car, the soundtrack suddenly blots out the loud engine sound, leaving only their words and inner reality. An inner reality perhaps plunging headlong to the abyss.

I am neither a celebrity nor a drug addict. Probably like you, I try to find better things. Maybe it’s in the simple joyous laughter of a friend as we share a glass of crisp wine. Birdsong outside my door reminding me of the countryside. The rustle of wind in the trees somehow recharging my batteries. Or the warm smile and embrace of a lover. Even if the affair is only desultory. We long for better things. And the empty space in which they are found remains a mystery. Someone asks, do I use films as an escape? If I do, creative films of this calibre risk giving Britain a good name.

Reviewed on: 23 Jun 2008