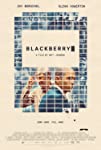

Eye For Film >> Movies >> BlackBerry (2023) Film Review

BlackBerry

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Every great invention begins with the recognition of a need. So in the early Nineties, we had mobile phones. Great. Phones are useful. But what if instead of just using them to make calls and send texts, we could use them for email (much cheaper and more efficient) and make them into mini computers? More to the point, what if we could do that using pre-existing infrastructure, at very little extra cost? “It’s like the force,” says Doug (played by director Matt Johnson). Then he realises that the guy he’s talking to has never seen Star Wars.

That guy is Jim (Glenn Howerton). Imagination is not his strong suit. He has no clue what Doug and his business partner Mike (Jay Baruchel) are talking about, but he does know that if it works, it will be worth a fortune. He doesn’t need to spend long with these wide-eyed young techies, who respond to stress by declaring emergency movie nights, to recognise that they’re not going to acquire that fortune on their own. In fact, they’ve already given away far too much of their idea to prospective partners, with the result that others are now hard at work trying to reconstruct their invention before they can bring it to market. Throwing his lot in with these people whom he would never spend time with otherwise, he gambles everything on making the PocketLink – quickly renamed the BlackBerry – a success.

The chances are that you’re already familiar with much of this story, but Johnson’s film, energetic and incisive and unabashedly Canadian, attempts to get at the personalities behind it, as well as exploring some of the financial issues involved in the way it fell apart. It’s driven by the tension between Jim, who argues that “perfect is the enemy of good,” and Mike, who contends that “good enough is the enemy of humanity.” Doug, with his red bandana and John Carpenter film quotes, finds himself increasingly sidelined, wondering what happened to the fun that used to make the job appeal to him.

The sudden appearance of a woman in the office, brought on board to look after payroll, leaves the confused techies looking as if they’ve suddenly found themselves on an unfamiliar planet. When Jim gets tired of doing all the shouting necessary to move things along, he brings in the still more aggressive Purdy (an inspired use of Michael Ironside), but with the competition from rival companies ever increasing, he’s at least as scared as anyone else.

There’s a lot of handheld camera work here, a lot of focus pulling and drift. We observe people through windows, track them as they walk past before losing sight of them behind various pieces of office equipment, see earnest faces striped by the shadows from Venetian blinds. It gives the impression of a lightly controlled chaos, where crises unfold with worrying frequency but everything is somehow kept in balance, at least for a while. This is a film built in the edit, a story which can but understood in linear form only in retrospect. With no such perspective, characters blunder around, their own senses of identity at stake in the mêlée.

With a lesser director at the helm, it would be all too easy to get lost here. Somehow, Johnson keeps it together, restricting his attention to the three central characters, letting emotion run high so that we can understand their passions even when the details of what they are dealing with are obscure. On the fringes of the action, tax controllers and financial service regulators are hovering like scavengers anticipating a feast. Johnson makes some bold musical choices, helping to establish both the era and the characters. When Jim first secures a deal, Love Will Tear Us Apart surges up triumphantly. The use of Joy Division as happy music tells us all we really need to know about this lonely, brilliant, floundering man. Mike, meanwhile, struggles to define himself by who he betrays, his hair growing slowly more grey.

There is nothing here of the slick image tech companies like to present to the world. Desks covered with wires and bits of circuitry briing us far closer to the real process of invention, and their tangled nature seems to extend into the surrounding officers. Sharp suits matter until they don’t. It’s disconcertingly easy to get out of one’s depth. In little cutaways, fingers tap away at keyboards underneath tables, the stealthy beginnings of the addiction which would ultimately drive the whole thing faster than any individual could keep up. Something has been unleashed which nobody can yet see, and though the things that they thought were important may slip out of their grasp, the world will be forever changed.

Reviewed on: 03 Mar 2023