Eye For Film >> Movies >> Boris Karloff: The Man Behind The Monster (2021) Film Review

Boris Karloff: The Man Behind The Monster

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

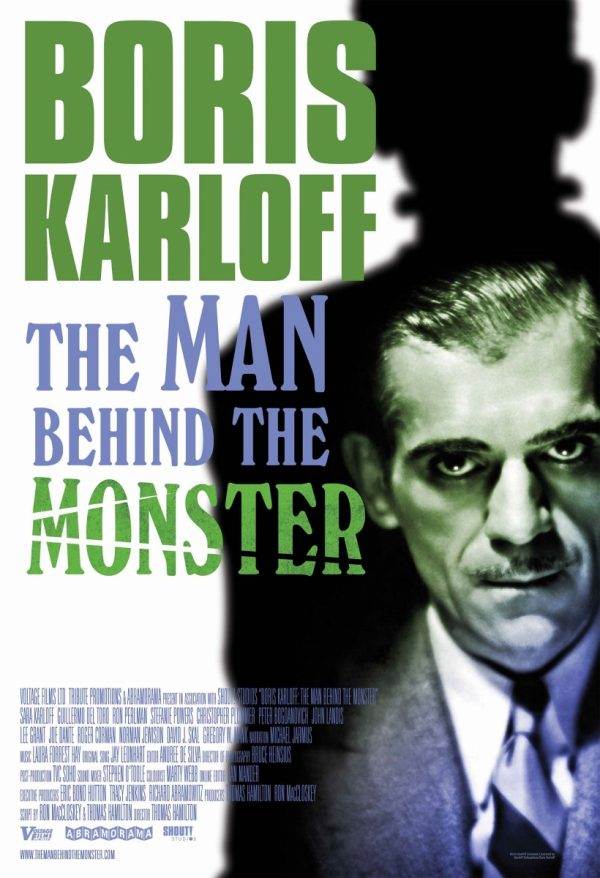

For a generation or more, he was the face of horror. No other face sent a shiver down the spine quite like that of Boris Karloff, and seeing his name on a poster at the cinema was a guarantee of a thrilling night out. Despite this, the man himself never attained the same type of celebrity status as his peers. He did the chat show circuit and so forth, but usually in character, revealing relatively little about himself as a person and successfully keeping his family life private. Now, almost a century after his heyday, this documentary brings his story to life and reveals the remarkable man behind the legend.

Though he was born William Henry Pratt, Karloff loved his screen name, so it seems appropriate to use it here. He hung onto it even when appearing in more conventional dramas, in which he showed a considerable degree of craft – he was much more than just the looming Frankenstein’s monster figure for which he is popularly remembered today. indeed, this documentary spends a fair bit of time on that iconic film and reveals how very different it would have been without his input. The pathos and sense of innocence which he brought to the monster would influence the portrayal of monsters of numerous kinds onscreen for decades afterwards, though to today, and it was culturally influential in the way that it taught generations of viewers to extend sympathy to the othered. Having grown up experiencing racism, with his darker skinned brothers getting it still worse, Karloff, whose parents had Indian ancestry, was always alert to an outsider perspective.

As director Thomas Hamilton illustrates here, that mixed ethnicity meant that Karloff was the go-to man for practically any non-white role in a horror film, including the horrendously racist (yet technically impressive) Fu Manchu films. in that era, and yet to make his fortune, it would have been difficult for him to reject such work, yet he still managed to bring an element of humanity to it. He seems always to have been aware that his ethnicity made his success precarious, beyond the usual precariousness which all actors experience. balanced against this, however, was an unrelated asset which advantaged him at a key point in his career. Whilst other famous names lost everything with the dawn of the talkies (fans who was swooned over Clara Bow, for instance, refused to accept her Brooklyn twang), his booming bass tones added another string to his bow and saw demand for his work increase.

Though it was his work in horror which made him an icon, Karloff took on an extraordinary range of roles over the course of his career. Towards the end of his life he made another successful transition, from the big screen to the small one, and clearly relished the different opportunities this presented him with. Hamilton interviews people who worked alongside him, as well as bringing in archive material, and what comes through again and again is the impression made by his professionalism. Even when his health declined to the point where he needed to carry an oxygen cylinder with him and could hardly walk, he could perform health. We see a clip from a programme he appeared on alongside his old friend Vincent Price, fully in command of the audience despite the fact that he was, reportedly, a fragile old man again when he left the stage. Having an audience to please seemed to breathe life into him like Frankenstein’s bellows.

Simple in its form, this film is nonetheless engaging throughout, shot through with interesting anecdotes and observations about what was going on behind the scenes. We hear some of the details of the star’s six marriages, which might have made headlines had his characters not overwhelmed public interest in who he was as a man. in archived conversation, we see him field potentially intrusive questions with consummate skill, using his dry humour to control the conversation. This film gets personal, however, with endearing reflections from his daughter Sara (who took his acquired second name despite him never having legally changed it). What emerges is not any nest of dark secrets but, instead, a legacy of great warmth and affection, with seemingly everyone who knew him having liked him – except perhaps James Whale, with whom he was constantly engaged in dispute. The director was known for wanting to have every detail his way, without much regard to the cost for the actors. This would spur on Karloff to become involved in the nascent Screen Actors Guild. Ironically, neither man would really get his way when it came to Frankenstein, due to the involvement of the censors. Analysing a key scene, Hamilton explores how this backfired.

Feeding in to all this are a host of genre greats, past and present: from Roger Corman to Joe Dante, John Landis, Guillermo del Toro, Ron Perlman and Caroline Munro. This contributes to a rich appreciation of Karloff’s work and its role in shaping the genre we know today. As the black and white horror classics, huge in their day, fade and become a niche interest, this is a pertinent tribute to one of the great legends of early cinema, and to a fascinating man.

Reviewed on: 27 Jan 2022