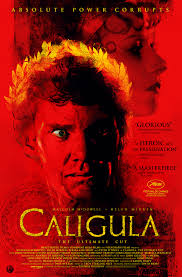

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Caligula: The Ultimate Cut (2023) Film Review

Caligula: The Ultimate Cut

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

One of the most controversial productions in film history, Caligula was first proposed in the 1970s, went through what can only be described as a series of catastrophes, and, in 1980, emerged as a version which would be abruptly disavowed by its editor, its composer, and the most prominent members of its cast. Central to their unhappiness was the decision by producer Bob Guccione, of Penthouse, to splice in hardcore porn, which not only caused offence in itself but effectively misrepresented the actors, and destroyed the original flow of the story.

Despite all of that, there was a kernel of genius in the film that led many people to fall in love with it, and it has continued to loom large in the cinematic imaginary. For year upon year, dedicated fans sought out the original footage, but it was believed that everything not used in the release had been destroyed. Then, in 2019, everything changed, with the discovery of over 90 hours of original negatives and audio. Producer Thomas Negovan’s reconstructed version uses nothing that appeared in the film as seen before. Premièred a Cannes in 2023, it is now finally getting a release in UK cinemas. Nearly five decades in the making, this is the stuff of legend, and it’s also a work of art that you won’t want to miss.

For those not familiar with the story at the heart of this other story, it concerns the Roman emperor Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known by the titular nickname, which translates as ‘little boots’ and refers to a childhood spent in army camps where he made himself a popular mascot by dressing up. He retained public popularity throughout his reign, but it ended abruptly after just four years. During this time his expenditure on public works like improving the empire’s roads made him a good many political enemies, as did his habit of sleeping with senators’ wives, but beyond this we know relatively little about him, most of the popular stories having emerged only decades or centuries after his death. It is largely out of those stories that this cinematic account of him is assembled, but even with that in mind, one might raise an eyebrown at the assertion in the closing credits: : “The story, all names, characters and incidents portrayed in this production are fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), places, buildings, and products is intended or should be inferred.”

One of the first things one notices about Negovan’s version – aside from the fact that it extends the already considerable running time to more than three hours – is how fresh it looks. Granted, it has that rougher texture peculiar to ageing celluloid, and in places – particularly when we get close-ups of faces – that’s less than ideal; but given that, when found, the negatives were believed to be rotting, no-one could have expected it to look so clean and so bright, with a depth of colour which today’s purely digital works have still not managed to capture. The restoration process has removed all trace of scratches and burrs, and backdrops which always looked a little rough have been digitally enhanced. This is of particular importance because the film was always intended as a visual feast, and in that regard it really delivers.

It is also an auditory experience, and of all the new elements, it is Troy Sterling Nies’ score that changes it the most. Gone is the sharp, satirical tone, which seems less than necessary in an era when we have no shortage of politicians aping Caligula’s mistakes. Instead this is presented as an epic, in keeping with Gore Vidal’s original script and with the grand tradition of historically-inspired films like Spartacus and Cleopatra. It belongs on the big screen, to a world of cinematic sensation beyond lightweight blockbusters and under-financed independents – a world which, fittingly for this subject matter, is struggling to survive under constant bombardment.

The central contention in Vidal’s take on the emperor’s life is that he lived much of it as intentional theatrical spectacle. Indeed, the early scenes when Tiberius (a wonderful Peter O’Toole) is still around suggest that he had precedent in doing so, and that, perhaps, this is perhaps what Rome needed from its emperors, to reassure the people that their figureheads were more than merely human. Perhaps it reassured senators, too, that those figureheads were men of leisure and not overly interested in politics. “The senate is a natural enemy,” Tiberius warns our young protagonist (played by Malcolm McDowell).

Tiberius, too, has invested in spectacle, and although the film has ditched the hardcore stuff, much of what is on display is sexual in nature. That said, the tone of it is very different. For the most part, the Roman nobles show little personal interest. It’s just another aspect of their display of luxury, of excess. Tiberius calls upon his slaves to perform sexual acts as if they were a theatre troupe, and he’s equally interested in performative cruelty towards those he considers deserving. Editing which places these elements back to back really sets the tone for the rest of the film.

Caligula, for his part, limits himself to strategic cruelty early on, ridding himself of potential rivals and those who know too much. A deeper vein of nastiness emerges in his treatment of a young noblewoman he desires, and her sweetheart. The scene at their wedding is filmed very differently from in the previous version, however, with the emphasis on faces rather than bodies, replacing any element of titillation with horror and allowing the sensitivity of the performances to come to the fore.

This approach applies elsewhere, too. The horse sex has been replaced by a rather sweet request from the fever-stricken emperor, waking up in a large bed beside his equine companion: “Will someone take my horse back to his own room?” The complex relationship between the emperor, his sister and lover Drusilla (Teresa Ann Savoy) and his famously promiscuous wife Caesonia (Helen Mirren) is portrayed as a tender polyamorous arrangement in which jealousy gives way to sympathy, rather than simply as a matter of sexual conquest. This allows for more focus on the impact of each woman on Caligula’s life, and he emerges as somebody whose story is interconnected with those of others, rather than as a man going mad as a result of his increasing isolation.

All of this gives McDowell a lot more to work with, and lets us see his creation as a more consistent character, mercurial (for all his love of Jove) yet possessed of his own sense of reason. We also see more of his humour, prompting us to question the assumption that he’s insane, at least in some instances. The shift in his psyche becomes something deeper, related to the terror and frustration he feels at his ability to make unreasonable demands with no-one stopping him, and his dawning realisation of what that implies about the universe. Some scenes from the other version are discarded altogether here. This may disappoint some fans but it keeps the story lean, despite its length, and overall it works better as a result. There is more sense of direction, more driving energy. Different characters come to prominence, with John Steiner’s Longinus, in particular, growing in stature, his keen eyes marking him as a potential foil from the outset. The bird motif which reappears at key moments is foreshadowed in the animated opening credit sequence and adds to the tighter sense of structure.

The consequence of all this refinement is a film whose wayward moments seem all the more marvellous. Rather than an exotic, sprawling mess, it is a work whose various wonders serve a purpose, even when that purpose is only to dazzle. It strives to fill the void left by the gods, and where it falls short, it is only more glorious as a result.

Reviewed on: 01 Aug 2024