Eye For Film >> Movies >> Cave Of Forgotten Dreams (2010) Film Review

Cave Of Forgotten Dreams

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

What draws you to read film reviews? When you read this, how conscious are you that you are placing your own interpretations on a set of words produced by me, using which I have placed my interpretation on a film made by Werner Herzog about his interpretation of a set of paintings made by persons unknown around 28,000 years ago?

If that sounds convoluted, let me add that the film is in English, Herzog's native language being German, and in places he translates (not always precisely) for other people speaking in French. In addition to this, some of those cave paintings are reworked or touched-up versions of older ones, some have been painted over the top of older ones, and the oldest and most recent ones may have been painted as much as 5,000 years apart. How much of the original intention has been lost during this process? How many new layers of meaning have been added? And to what extent is this process of artistic evolution an essential aspect of what it means to belong to the human species?

"I used to be a circus performer. No, not a lion tamer. Mostly unicycling and juggling," says a young geologist working on the business of interpreting the paintings in Southern France's famous Chauvet caves. It's one of those quirky little flashes of insight that other documentary makers long for, and that Herzog seems to capture in almost every interview. Later in the film we are to meet a former president of the Perfumers' Association of France, a stocky man who now roams that landscape (where we are told Neanderthals lived as the peers of the painters) sniffing at the rocks, hoping to catch the scent of hidden caves. If there is anybody who can provide insight into the lives of those long-vanished it must be Herzog, yet he likens the process to using a phone book to try to understand how people in a modern city live - their families, their loves, their hopes and dreams. In the splendid cave, perfectly sealed by a rockslide for thousands of years, lie dreams long forgotten, but it is very difficult for us to look at them now and understand what they must have meant to their creators.

This is Herzog's first film in 3D. There's something almost unholy about watching a 3D film at a festival (it was the GFF where I caught this), but this is unlike any 3D film you will have seen before. We begin in a ditch in a rutted field, down close to the ground, blades of grass leaning toward our faces, insects drifting by. Our journey carries us toward the cave entrance; soon we will be travelling deep inside. To do this, working in confined spaces, a special camera rig has been designed. This has led to some technical problems, especially in outdoor scenes, where the 3D effect becomes uncomfortably skewed - you may well feel a bit seasick. Inside, however, it works wonderfully, and captures aspects of the paintings which I had certainly failed to appreciate in the past when seeing 2D copies of them.

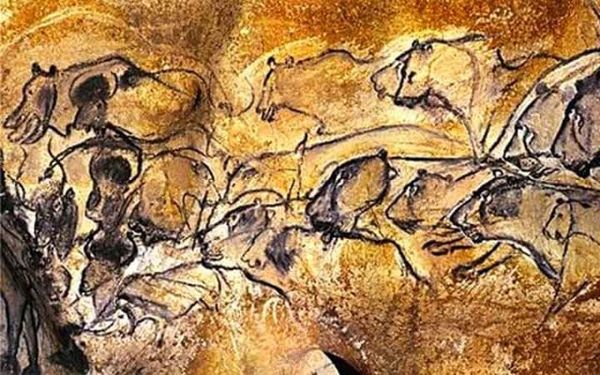

Now we can see how the painters used the three dimensions of the rock, all its curves and bulges, to bring their paintings to life, giving them depth and texture. This is representative, not symbolic art. One painted lion has eyes that appear to move like those of the Mona Lisa (a trick which requires advanced understanding of geometry). These are techniques we tend to associate only with the last few centuries; they show remarkable sophistication. Some animals are painted with whole or partial extra legs. By firelight, Herzog surmises, they would appear to move, like a form of proto-cinema.

If looking at a bunch of old paintings sounds pretty dull to you, you may well find this film too slow, but there are moments in it when even the most cynical viewer could not help but be impressed. The vast gulfs of time across which these images have travelled to speak to us is difficult for us, in our young civilisation, to comprehend, but of course the painters probably had a very different intellectual relationship with time itself. Alongside this, occasional failures of the imagination stand in stark contrast. One painter, we are told, must have been six feet tall to complete a particular set of images; another must have painted using a stick. One cannot help but wonder, 'primitive' though they were, if those ancient people really had still failed to invent the technologies of standing on stuff or lifting up a friend on one's shoulders. This serves as a reminder that, with only a very small group of scientists working full time to understand the secrets of the cave, pet theories may sometimes obscure more thorough analysis, adding yet another confounding layer to that long sequence of interpretations.

Ultimately, Cave Of Forgotten Dreams is as close as you are likely to get to being able to see the Chauvet paintings for yourself, and on that basis alone I highly recommend it. Herzog fans may not consider it one of his greatest works but they are unlikely to be disappointed. If you are not adequately awestruck by the shared dream in itself, wait until you come face to face with the destiny of the albino crocodiles.

Reviewed on: 19 Feb 2011