Eye For Film >> Movies >> Creep Box (2023) Film Review

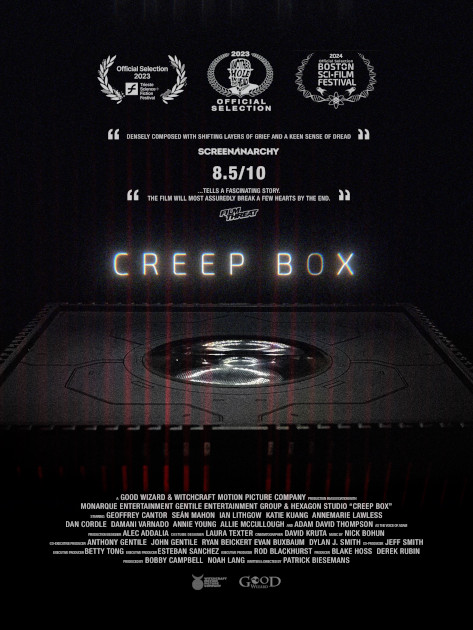

Creep Box

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Given the escalating pace of technological development, it’s getting harder and harder to make science fiction films that don’t look like reality by the time they’re released. The genre has always had an important role to play in kicking off ethical debates before we need to start making particular big decisions in practice, but today the timeframe we have to do that in is getting shorter and shorter.

The day before I watched Patrick Biesemans’ Creep Box, I was party to a discussion about new technology which recreates the voices of people’s deceased loved ones, even if they have very little audio available to work from. Voice simulators like Lyrebird have been around for a while and we have already seen such technology used in scams, calling people up, impersonating their loved ones and asking them to wire money. What’s changed just recently is that it can now capture an individual’s intonation and habits of speech in a far more convincing way. I felt immediately that it wouldn’t work for me – what I miss about my dead is my awareness of their experience, of their capacity to learn and change – but a friend told me that being able to have conversations with her dead husband has helped her tremendously in dealing with the loss.

Inevitably, these technologies will advance further, and Creep Box posits a world in which they have. The project developed at HTD goes beyond mere speech and mannerisms to create a simulation of consciousness, or so the company claims. Consciousness with its various layers (described with reference to the Freudian id, ego and superego, though in reality some people have more than three) presented as overlapping voices, which creates an interesting experience for the audience – you may want to watch the film several times to catch everything that’s being said. Then there are the focus words. “Meadow. Domineer. Twitch. Scent. Sunset. Vanilla bean. Peacock.” These work for Rachel Nichols. They mean something to her, enough to bring those layers together, to get her attention.

Hers, or something else’s? ‘She’ is, the company stresses, nothing more than a simulation, a string of ones and zeroes, with somebody else’s memories. Of course she’s called Rachel. Her husband, one of the project’s funders, is Henry, and Lovecraft fans may be minded of a certain Mr Wentworth Akeley. Given access to this contact he has longed for more than anything, he is cautioned to follow one rule: “You must avoid any reference to the here and now.” Of course, he breaks it. This may be science fiction but it’s built upon a far older, folkloric form of cautionary tale.

If it’s a stressful encounter for Henry, it’s also upsetting, in a different way, for Dr Caul (Geoffrey Cantor), the lead scientist on the project and the man in whose company we spend most of the time that follows. For the first time, he carries out the process on a child, taking material from the brain of the dead boy to try to help Department of Justice investigators find out how he and his father were killed. At the same time, his research interests bring him into contact with Adam, a man who doesn’t seem to suffer the same degradation of consciousness over time, apparently because he killed himself. interested in the project and willing to contribute to its development – at least as Caul interprets the situation – Adam asks difficult questions. Has his consciousness been simulated, or has it been captured? is this what consciousness is?

It’s one thing to ask questions with a film like this – quite another to propose answers. Ultimately Creep Box sidesteps some of the more difficult ones, but it manages not to be annoying in doing so, avoiding the twee solutions which plague the genre. Cantor is effective in embodying a troubled man who is not as conscious of himself as perhaps he might be, and whose psychological arc fits in neatly alongside the rest, eventually becoming the dominant narrative strand and bringing events to a satisfying conclusion. This also enables the film to explore the other part of the equation: the human experience of grief and the different ways in which it can manifest, changing the relationships we have with the dead.

There are playful moments here, with some genre-specific dialogue that will make viewers smile. There are also painful glimpses into other people’s grief. One might recall that it is only for a little over a century and a half that we have been able to hear the voices of the dead at all. That’s not much time, as a species, to adjust. What it means for someone to be dead has changed and is continuing to do so. Creep Box, low budget but high concept and benefiting from great design work throughout, tests boundaries and thrives in uncertain spaces.

Reviewed on: 02 Apr 2024