Eye For Film >> Movies >> Death Proof (2007) Film Review

Comprising a double-feature of Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof and Robert Rodriguez's Planet Terror (as well as mock-up trailers during the intermission), Grindhouse was originally conceived as a grittily nostalgic revival of the whole 'grindhouse' experience - yet another groovy time-warp to add to the countless Noughties remakes, reimaginings and rehashes of Seventies cinema. Yet despite considerable critical acclaim, Grindhouse was a relative failure at the box office, so that the Weinsteins took the decision to release Grindhouse abroad as two separate films, much as they had previously asked Tarantino to split Kill Bill into two separate volumes.

This represents a double curse for viewers in Britain, struggling to 're-live', under far from ideal conditions, an experience we have not 'lived' in the first place. Not only is this a nation that has never really had an equivalent to 'grindhouse' cinemas even in the Seventies (though still going strong, the whole 'fleapit' phenomenon hardly counts), but what is more, the only hope we have of enjoying the 'grindhouse' experience as Messrs Tarantino and Rodriguez intended is eventually to watch the inevitable double-feature DVD release. Believe me, even if your home is a sticky, smelly tip, even if it is frequented by some very dubious guests, even if it is the location of casual sex, drug-taking and violence, it is still even less like a grindhouse than your local multiplex where the films were originally supposed to be seen together.

Now emasculated and split right down the middle, Grindhouse is no longer a bold cinematic experiment, but rather just two vaguely related homages to exploitation cinema - and the exploitation is directed squarely at us viewers, forced as we are to pay twice the admission fee for considerably less than the full experience. In an apparent bid to soften the blow, we are getting reworked, expanded versions of the original films - but if Death Proof is anything to judge by, this is just adding insult to injury. Death Proof feels exactly like what it is: a 90-minute film that has been stretched painfully to 114 minutes. There was always a reason, beyond mere budgetary constraints, why exploitation movies were short, and the reason is perfectly illustrated by Tarantino's overblown, patience-stretching re-cut.

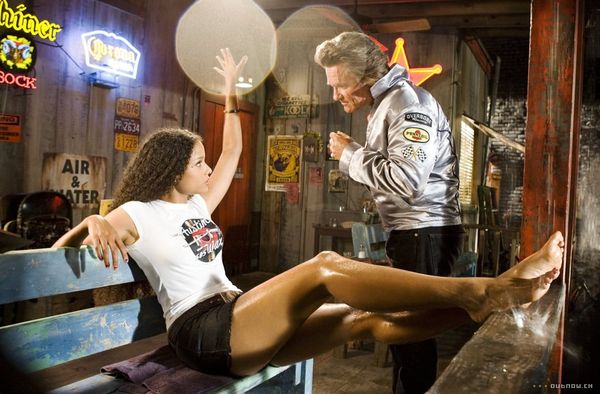

The premise of Death Proof is rock solid. Divided, like the original Grindhouse, into two parts, it begins with three young women (Sydney Tamiia Poitier, Vanessa Ferlito, Jordan Ladd) having a night out on the town in Austin, Texas, little realising that they are being stalked by Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), an unemployed old-timer with a steel-reinforced stunt car, an unreconstructed attitude towards the opposite sex and a nasty penchant for 'vehicular homicide'. After a hilarious interlude with regular Tarantino character Sheriff Earl McGraw (Michael Parks) and his son Edger (played by Parks' real son James), the film's second part kicks in. A fresh group of young women (Tracie Thomas, Rosario Dawson, Zoë Bell, Mary Elizabeth Winstead), all in Lebanon, Tennessee to work as crew on a film, cross paths with an unreformed Stuntman Mike and give him a glimpse of their own line of cunning stunts.

Eschewing his usual narrative leaps in time, Tarantino allows his stories to unfold in strict chronological order - but still cleverly confounds one decade with another. Death Proof deploys a range of filmstocks (from true black-and-white to luscious technicolor) and tricky gimmicks (distressed reels, scratches, 'random' jumpcuts, etc.) to mimic the look, feel and grain of the grindhouse era - and yet its characters, with their iPods and cellphones, are not so much living in the Seventies as reliving the glories of that age in our own postmodern times. To them, live stuntwork will always be superior to CGI, making a compilation tape is a more romantic gesture than burning a CD, and nothing could be cooler than test-driving the same make of car (now vintage, of course) once driven by Kowalski in Vanishing Point. Such retro attitudes are naturally shared by the director, who even manages to film a woman text-messaging her boyfriend in the full style and spirit of the seventies - a true miracle to behold, in all its preposterous paradoxicality.

So sure, Tarantino's debut as cinematographer (he has been writer, director and producer many times before) is lovingly shot. Sure he manages to mix together slasher, chase and revenge genres into the guiltiest of guilty pleasures. Sure he pulls off some old-school, CGI-free stuntwork that will have viewers drooling into the aisles with mouths agape. Sure he throws in endless in-jokes and genre-savvy references for the inner circle of filmgoers who have come to expect and cherish this sort of self-reflexive sensibility from him. It even has Tarantino's trademark foot fetishism aplenty from the get-go. Yet what sends Death Proof crashing off the road is its writing, making it far and away his poorest film to date – although even at his worst, Tarantino is always worth watching.

Tarantino has been (rightly) praised for the hip quality of his characters' lines in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction (leaving aside the excruciating erotic banter between Bruce Willis and Maria de Medeiros in the latter) - and he has been (wrongly) criticised for stripping the talk down to a bare minimum in the Kill Bill films. Death Proof, however, is the first film in which Tarantino has used dialogue as mere padding. Each of its two parts consists of a visually striking beginning, an orgasmic climax (in a film surpassed only by David Cronenberg's Crash for its equation of sex with violent collisions) - and in between, smug, seemingly endless verbiage that does not so much establish character as ram it down the viewer's throat.

You will get within the first five minutes that these are smart, strong, independent women who call the shots in their relationships (or at least say that they do) - but to hear these ideas repeated over and over and over suggests that Tarantino has literally lost the plot, foregoing narrative drive for loquacious idling. It makes what ought to be an economic burst of schlock instead stay stalled in neutral for most of the (overlong) duration. This, more than anything else, will leave viewers nostalgic for the old grindhouse days (or at least for the original Grindhouse), when such countercultural sleaze was as short and sharp as it was sweet.

Reviewed on: 05 Sep 2007