Eye For Film >> Movies >> Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (1924) Film Review

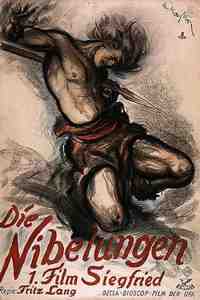

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

One of the most successful epic poems in history, one of genre cinema’s most influential writers and one of its greatest directors – right from the start, 1924 silent diptych Die Nibelungen was destined to be something exceptional. Released at a time when fewer prints were made and films took their time to travel internationally, it never really received its due internationally, with the second part, Kriemhild’s Revenge, unlucky to be impacted by the emergence of the talkies. Nevertheless, it acquired legendary status in critical circles, and its hundredth anniversary celebrations included a special screening at Fantaspoa 2024.

Die Nibelungen has suffered in other ways since Harbou and Lang practised their craft, with the myth co-opted by the Nazis and used as part of their promotion of German nationalism (one can only assume that they never actually read all of the poem, nor learned the lessons obvious to its author 700 years previously). It can be difficult for a modern audience to set that aside, and yet the films are quite different in flavour and Lang’s emotional distance allows the story to unfold without sensationalism or judgement, preserving its critical moments of ambiguity.

The fantasy setting goes a long way towards resolving the difficulty in suspending disbelief which can grow over time as filmmaking techniques are superceded, making the films accessible to audiences even if they have no appreciation of their place in history. This first part is notable as the first major work on celluloid to use mist and long light in the creation of a magical forest landscape, something still imitated by filmmakers to this day. It also set the standard for countless epics with its fantastic castle, its inaccurately armoured knights and its scantily clad hero, whose toughness is first betokened by his ability to wander round Germany by day and night in nothing but a miniskirt without freezing to death.

We need that indicator because, truth be told, Siegfried (Paul Richter) doesn’t really do very much. He has one big battle with a dragon and from then on he had massive magical advantages in every task – not so different from today’s popular superheroes, then. The dragon is awesome. Bear in mind that this was before The lord Of The Rings was a twinkle in Tolkien’s eye. There was no set notion of what a dragon should look like, with notions across Europe different wildly. Lang bases his on a crocodilian shape, with additional spines. it’s a lumbering thing, so that Siegfried’s initial attacks on it seem rather unfair, but when it breathes fire, the scene suddenly becomes thrilling.

This was real fire, of course, before any significant alteration of the image in post was possible. The special effects rig is impressive, not least because when the beast is eventually stabbed in the throat, copious quantities of water blood gush out of it. This is the cue for a watching bird (which looks notably less artificial that David Lynch’s famous Blue Velvet robin 65 years later) to inform the bold young man that bathing in the blood will render him invulnerable. He doesn’t hesitate to believe the bird, discarding his remaining clothing in a scene which viewers might have found shocking 30 years later.

Siegfried had been on his way to Worms to seeks his fortune, but now things look a little different. We see his subsequent, rather more unfair battle with an invisible Nibelung, and his subsequent acquisition of a treasure from a fantastic underground grotto which again establishes a fantasy cinema archetype. We then sought of skip through the bit where he conquers 12 kingdoms – it never was very well fleshed out – and the second half of the film deals with his romance with the princess Kriemhild (Margarete Schön), in pursuit of whose hand he has to assist her brother King Gunther (Theodor Loos) in his pursuit of the famously independent Brunhild (a magnificent Hanna Ralph).

In earlier tellings of the tale, Brunhild was often presented as villainous, but Harbou and Lang clearly feel a lot of sympathy for her. There is, after all, not really much difference between the thing she will allege in response to her treatment and the thing that has really been done to her, as she is forced into an unwanted marriage through trickery and violence. These abusive acts are what will eventually lead the two men’s plans to unravel, with Gunther’s advisor, Hagen Tronje (Hans Adelbert Schlettow) poised to take advantage as he seeks to regain the power which Siegfried’s influence on Gunther has depleted.

The action, scored by Gottfriend Huppertz with key extracts taken from Wagner’s opera, is divided into cantos with chapter headings to help work around the difficulties posed by lack of dialogue. Relatively few intertitles are needed, with the strong cast capable of communicating most of what matters in other ways. They’re aided by Lang’s innovative techniques, which include the use of back projection for a key scene in the grotto and layered imaging to let us get ghostly glimpses of Siegfried when he’s aiding Gunther. There’s an almost seamless moment in which the real Gunther and his double appear side by side, which must have wowed audiences in its day. The only real disappointment on the magic front is the legendary sword Balmung, wrought from fire and blood and yet still looking like rather underdressed aluminium.

Paul Gerd Guderian and Aenne Willkomm’s costumes are an amazing asset, drawing on old Scandinavian designs and runic motifs. Siegfried’s lines and zigzags make him stand out as a dynamic figure even when he’s just sitting about, whilst the little leaf-shaped motifs on Gunther’s clothing remind us that he has always enjoyed prosperity without the need for martial prowess. Kriemild’s ridiculously overdone braids will immediately call to mind Rapunzel, and she strikes a good damsel in distress pose, though even here – before she really comes to prominence in Part Two – we get glimpses of a darker side, a petty viciousness that will be her undoing.

As if to compensate her for the indignities she suffers, Brunhild gets the best of the clothes, from the great feather-winged helm she wears as commander of her own castle beyond the lake of fire, to the stunning Art Deco gown and jewellery she wears at the moment of committing herself to revenge. Nonetheless, it’s Ralph’s eyes you will remember, full of fury, commanding the screen.

With later shots of the woods drawing inspiration from late Medieval paintings, and with good use made of the bridge leading to the gate of Gunther’s castle, one of the few sets that has to bear weight, Lang really makes us believe in the setting, just as he makes us believe in the grand scakle of it all despite having only about 30 extras. It’s a masterpiece, the true foundation stone of fantasy cinema, and if you get the chance to watch it on a big screen, you shouldn’t miss it.

Reviewed on: 20 Apr 2024