Eye For Film >> Movies >> Filmmakers For The Prosecution (2021) Film Review

Filmmakers For The Prosecution

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There’s a theory that when people have absurd amounts of power over others, they often do horrific things to those in their power as a means of testing boundaries and reassuring themselves of their status, and that they make records of those things to reassure themselves that their power will exist forever. Psychologically, they find it increasingly difficult to be rational about the possibility that their situation will change. This is sometimes cited as one of the reasons why senior Nazis became deluded about their capabilities and lost the Second World War. It very likely played a role in Nazi decisions to film atrocities as they were carrying them out, not just for the sake of bureaucracy but, as is explained here, for after dinner entertainment.

When we picture the Holocaust, most of us immediately find our minds turning to black and white images of starving, skeletal people pressed up against fences or engaging in forced labour. Most of those images were not captured by rescuers or spies, but by Nazis themselves. After the war, there appear to have been concerted efforts to conceal or destroy them. At the same time, as the Allies prepared for the groundbreaking Nuremberg trials, a US team raced to retrieve as many of them as possible, to compile the evidence which could supply irrefutable proof of what happened.

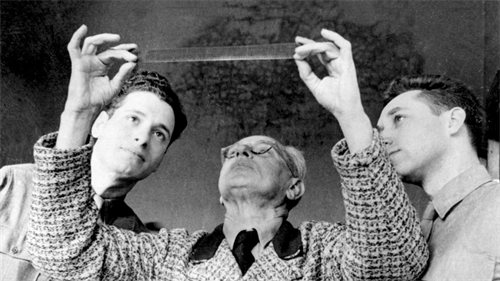

Who were these people? This documentary introduces us to two brothers whose names previously languished in obscurity: Marine Corps sergeant Stuart Schulberg and Navy lieutenant Budd Schulberg, who had grown up working with film as the sons of powerful early Hollywood producer BP Schulberg. They were commissioned by none other than John Ford, the legendary director recently portrayed by David Lynch in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. He was working with US spy organisation the OSS, but the brothers still had to do much of the legwork themselves, hunting down hidden material. Stuart’s daughter, Sandra Schulberg, appears briefly here, captivated by the first footage she has ever seen of her father as a young man. Her presence reminds us that this is far from ancient history.

There are some wonderful moments here: those little coincidences on which the fate of the world turns. With relations between the US and the Russians growing frosty in the run-up to the Cold War, the brothers might never have accessed footage recovered by the Russians, and the trials might not have been as successful, were it not that a certain Russian commander happened to be a massive John Ford fan.

Even the footage which we have of the trials themselves, again taken for granted today, turns out to have come close to not being recorded. Whilst some argued that it could make an important contribution to de-Nazification efforts in Germany, there were concerns that it might disrupt the serenity of court proceedings. It is fascinating here to film of people at the trial – including Goering and Hess – watching the Schulberg brothers’ compilation of recovered Nazi films for the first time, to catch the moment when the mood shifted and a new international understanding of what had happened emerged. As the other defendants left the courtroom that day, Hans Frank, who had headed up the occupying forces in Poland, just sat there staring at the screen. His son speaks here, reflecting on a lifetime of denial and his own certainty about what his father was.

Building up a positive narrative about how filmmakers used their skills to ensure that justice was done at these early trials, the documentary then takes a darker turn, looking at how geopolitical shifts led to the brothers’ ongoing work being suppressed. It would be many years before it was widely seen. Certain Nazis became useful and their new bosses didn’t want to see them jailed or executed. Senior military staff got nervous about the setting of precedents about who might be held accountable for crimes committed in wartime. Powerful forces wanted the world to forget. Films were directed at re-education in Germany but it was argued that the US was different and did not need to learn those lessons.

Only an hour in length, this documentary is nonetheless hard hitting. Its brevity leaves one feeling as if something is missing, but perhaps that’s the point. It ends on a mournful note, reflecting on where we are today. There is no need to illustrate that; no need to look at how filmmakers strove, in the interim, to bring the Holocaust to life for successive generations. The moment was lost. We can see here, how education got as far as it did, and be reminded that film does matter in the real world – and, perhaps, have a better idea what to do if we should find ourselves in that situation again.

Reviewed on: 20 Jan 2023