Eye For Film >> Movies >> Frost/Nixon (2008) Film Review

I’m old enough to remember, vaguely, the televised Frost/Nixon interviews. Even the presidency. And the US/VietNam war. I shared the popular sense of moral outrage. But I’m not an American citizen, and I couldn’t get worked up about ‘giving Nixon the trial he never had’. What difference did that make to me?

Something halfway through this movie changed my mind. Mid-interview, attempting to get a reaction from Nixon, Frost’s team run footage of carnage in Cambodia caused by American carpet-bombing. I guess perhaps because I was in Cambodia only a few months ago, it made more of an impact. For all my intellectual appreciation of events, I hadn’t been prepared for such devastation of a nation’s psyche.

An NGO worker looked into my eyes one day at a truck stop. She said: “When I got here, I just cried every day for weeks.” I think she knew, as our eyes met, that I, a grown man, had been crying in helplessness towards these people trying to hide my tears for days. Visiting the ancient temples and aid workers, but meeting villagers, too, it was hard not to cry. I have never seen a people so psychologically annihilated. The first thing that had struck me was, here is a nation for which the very idea of hope has been long ago discarded. I wanted Nixon to pay.

The horrific footage doesn’t move Mr President, the way it moves me. I want him to have that trial. But Nixon is a heavyweight in every way, just like the actor portraying him. Frost, on the other hand, seems like a bit of a joke. Hardly a man to bet on. Yet from that moment I was rooting for him. The only person with a chance of bringing light into Nixon’s disingenuous stonewalling. From that moment, I was emotionally hooked. I would happily overlook all but the most egregious of flaws.

Fortunately, like the real interview series, the film only gets better. As if it has been playing with us for an eternity before packing its punches.

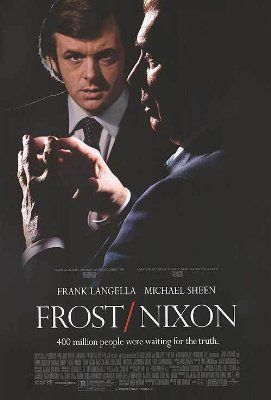

I’ve never been much taken with Michael Sheen (Frost). I kept thinking of his performance as Tony Blair in The Queen and how, here as in The Queen, it seems too much like an impersonation. Rory Bremner on a good day. But it is almost Sheen’s fallibility that allows the rest of the film to shine. Taking us off guard, just as Nixon was taken off guard. A cheap punk on the street whom you might walk past disparagingly, only to realise he’s the mafia boss and you’re surrounded.

Then there’s Kevin Bacon. Haven’t I seen that suit in one too many movies? So when he hits me with real emotion towards the end (he’s a very good actor) it creates a profound shock. Both these men know how to play supporting actor in the true sense, supporting the lead role and the whole production rather than constantly making us notice their own lapels. But it’s Frank Langella’s towering interpretation of Nixon that eventually makes every other character real. Low-angle camera shots emphasise his power and he looms over us. The most powerful man in the world. And once we buy into that, everything we see in his ‘world,’ by definition, has to be ‘real’.

Frost/Nixon is about as watertight as you get. Adapted by the man who wrote the play (and also wrote The Queen and The Last King of Scotland); then an Oscar-winning director who only agrees to do it if he can have the two lead actors from his polished stage version. Remember how Ron Howard pulled the equally dry-seeming A Beautiful Mind out of the bag? Well, he’s done it again.

But for all the triumphant battle cries as Frost walks him into a trap, in the end it is Nixon who gets my sympathies. Even more than Frost gets my admiration. As I watch Nixon face his inner hell, I recall every speck of darkness in my own soul. How I never managed to make my father proud before he died. How I risked my career once when I stole a long international phone call in the office. How I cheated on the one woman I loved more than any woman in my whole life. Some sins just don’t go away. Nixon becomes the Nemesis within Everyman.

Nixon, like a Judas Iscariot or Lady Macbeth, has no way of ever becoming completely clean. But, through the ironic good fortune of an interviewer who outwits him, he receives the gift of being able to say sorry. Sorry to the Americans he betrayed. His legacy, the symbol of ultimate duplicity – the “-gate” tagged on to any word to indicate scandal. See him fall – is it then possible (for some perhaps) to open hearts and forgive?

The second biggest thing that is striking about Cambodians is their lack of ill-will to the one who destroyed their country. Having never hated, they have nothing to forgive. A senior monk instructed me, while I was there, on a Buddhist method of mindfulness. One of the results of this mediation is that one focuses everything back on one’s own action, and hence one’s own moment-to-moment responsibility. It strikes me that for Nixon, Frost was like the senior monk. The guy who showed him how to face who and what he was. His catharsis. Not that anyone will ever say thank you (to Nixon, that is.)

And coming full circle, that’s what cinema can do. It can take something that is intellectually discernable and make it real – through an emotional investment. And it does it by means of fiction.

Reviewed on: 06 Jan 2009