Eye For Film >> Movies >> Oh, Woe Is Me (1993) Film Review

Oh, Woe Is Me

Reviewed by: Chris

Are you easily distracted?

When I first watched Gaspar Noé’s 2002 film, Irreversible, I sat near the screen and found the cacophony of images overpowering. On my second viewing, I sat further back, more easily contemplating the ‘bigger picture,’ appreciating a remarkable film. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway suggests a similar psychology in her ‘stream-of-consciousness’, where writing emulates experience: we need to step back before we can tell what is the pertinent information? What is the story about? In real life, we may only see things in true proportion retrospectively.

This psychological hurdle forcefully confronts us in Hélas Pour Moi. I strongly urge you to see it twice if possible. The story is more logical and flowing when you know what is happening. You can appreciate the many subtleties and the exquisite cinematography of Caroline Champetier. Failing that, I would recommend sitting at the rear of the auditorium.

We meet a publisher, Abraham Klimt (Bernard Verley). He has turned detective to investigate a strange story sent to him of divine intervention, though part of the manuscript is missing. We catch up with Klimt as he seeks out Simon and Rachel Donnadieu, our main characters, as well as the one witness who maybe saw the key event: did God take human form to have sex with Rachel by inhabiting the body of Simon, her husband? We are subject to the same sort of events-discordance, people coming and going, conversations overlapping, as Klimt might encounter as he searches for truth in an unhelpful environment. This non-sequitur approach goes on for ages, and only in the last 30 minutes or so of footage does the story congeal for a first-time viewer.

It re-works a play based on the legend of Zeus, Alcmene and her husband Amphitryon. In the Ancient Greek, the divine Zeus takes the human form of Amphitryon to mate with Amphitryon’s betrothed. In the original, this leads to the birth of Heracles, born of divine father and human mother. But in Godard’s modern setting, the story just goes as far as sexual union. God, once known as Zeus, now seems more Christian, and by implication can even lead us to question the veracity of the standard Mary-and-Joseph story. Klimt has no preconceptions: he just wants the truth.

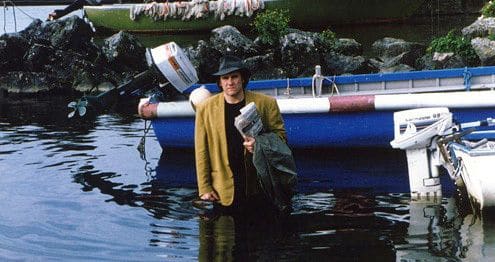

There is no strong statement on whether one should believe in divine intervention, or just go for the more obvious explanation: that Simon, although estranged, is feeling horny and assumes a divine persona which the ever-devoted Rachel believes. “All men are the shadow of God to the women who love them.” (We do, however, see a low-budget and highly effective scene where God, looking rather scruffy and unkempt, enters Simon’s body.)

Godard called Hélas Pour Moi “a complete flop”. Yet, while difficult and obscure, it garnered critical praise and was his first feature to be distributed in the US for ten years. Depardieu (who plays Simon) abandoned the film halfway through shooting, exasperated at Godard’s methods. “It could have been a good movie,” said Godard, “if Depardieu was willing to try. But he was not interested in the movie, in working to make it right. Of course, he said, 'Godard is a genius.' He was just making it for my name.” But without Depardieu, the film would not have been financed.

Hélas Pour Moi is replete with dozens of obscure references (from French and Italian literature, from philosophy, from theology) and quotations have sometimes been ‘edited’ by Godard. This makes it a particularly difficult film even if it wasn’t so already. In the jangling, difficult-to-watch first two-thirds, apparently discordant ideas and images are set against the beautiful backdrop of nature and Lake Geneva. Such style is intrinsic to the content. “I feel a strange revulsion at the thought of crudely expressing what the spectator has probably guessed of his own accord,” says Klimt, but the words could have come from Godard’s own lips.

For a while, I wonder if the film will develop into a polemic against religion – no stranger to Godard’s virulence – perhaps replacing it with art as the highest of aspirations. Yet, “there is always something depressing about the portrayal of crude reality,” and belief is heralded in what could be interpreted as a positive light when a character asserts, “I believe because it is absurd.” When logic fails, after all, we are left with belief. And what is truth? “Truth is what keeps the walls of houses upright, what keeps the roofs from collapsing.”

This is just one reading. We could view the film as an essay on human feelings. An enquiry into sexual union as an aspect of communicating with God (Rachel likens the gesture of hands in prayer to hands folded in an embrace around one’s lover.) Or how an artist seeks meaning in the world. Or we can follow the poetry of Champetier’s photography, enjoying the way subjects are framed in nature, focussed and de-focussed, and the beauty of the moment as a bicycle falls over, or a woman’s hat blows off. As a feminist study, or as the way history (and literature) is created and redacted: the French words ‘histoire (history) and ‘histoires’ (stories) being symbiotic for Godard - who entitled his history of cinema ‘Histoire(s) du Cinéma.’

Metaphysical aspects are drawn together in the opening, and in the final coda, halfway through the credits. These skilfully harmonise Godard’s ideas on the nature of perception and the evanescent nature of truth.

“When my father's father's father had a difficult task to accomplish, he went to a certain place in the forest, lit a fire, and immersed himself in silent prayer. And what had to be done was done.” The ritual was diluted over time. “But we do know how to tell the story." Never shy at innovation, Godard tells his story in a new, deep and meaningful way.

Reviewed on: 09 Oct 2012