Eye For Film >> Movies >> Howl (2010) Film Review

Great literature, in the form of novels, short stories and drama, has provided a treasure hoard regularly plundered by filmmakers over the years. But how do you make a film about a poem?

One could argue that the impact of a work of poetry is always too personal, operating on a level of pure emotional resonance, to ever be satisfactorily replicated in the cinema. Fortunately writer/directors Epstein and Friedman didn’t agree. The result is a powerful, ambitious and ultimately very moving study of one of the most important works – not just of poetry, but of literature itself – in the modern era.

In some ways, Ginsberg’s 1955 poem is an ideal choice for the cinematic treatment. Its publication created a huge controversy that led to an obscenity trial, it cemented the image of the ‘Beat Generation’ poets – young, hip and righteously angry at what they saw as the puritanical hypocrisy of the Eisenhower era – in the public’s mind and its author was a complex, charismatic but deeply troubled product of America’s ‘Golden Age’.

It’s also an extremely dramatic work – but in a free-flowing, stream of consciousness way. There’s no central narrative and much of its imagery is elliptical and allusive. The filmmakers tackle this problem by taking three separate narrative paths: transcripts of contemporary interviews with Ginsberg, recreated by Franco, intercut with flashbacks to his earlier life and a recreation of the poem’s first public reading; a recreation of the 1957 obscenity trial, where an attempt was made to halt Howl’s publication in book form; and animated interpretations of the key moments in the poem itself.

All these strands are constantly intercut, making for an intense and often disorienting cinematic experience. But also a richly rewarding one. At a time when poetry only makes the news in the context of the major prizes being awarded, or the odd bust-up between Oxford professors, it’s a reminder that Ginsberg’s work genuinely scandalised an entire nation and forced it to take a long, hard look at itself.

The Beat Generation artists – and the shorthand image they helped create, of the polo-necked slightly pretentious jazzcat lounging in a Greenwich Village coffee bar – are now so much a part of America’s cultural landscape that Howl was once referenced in The Simpsons, but at the time Ginsberg’s stark descriptions of gay sex, drug use and mental illness outraged – as ground-breaking art often does – the self-appointed guardians of public morals.

Many of the film’s more light-hearted moments come when they take the stand in the trial scenes. Parker is outstanding as a buttoned-up radio personality, icily dismissive of the poem’s language and artistic merit, as is Strathairn’s prosecuting attorney – a classic old-school American conservative offended less by Howl’s ‘obscenity’ than by the fact that it doesn’t really seem to ‘mean’ anything.

Ranged against him is Hamm’s defence lawyer – a sharp-suited alpha male not a million miles from Don Draper, but possessing a keen eye for prejudice disguising itself as literary criticism. His final speech to the judge in which he argues that art should not be banned simply because some people disapprove of it, is an old-fashioned piece of Hollywood barnstorming and none the worse for that.

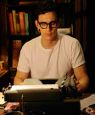

But the real standout performance is Franco’s. After his best friend/villain turns in the Spiderman series he seemed to get stuck in unchallenging eye candy roles like Flyboys and Tristan And Isolde. But this and Danny Boyle’s upcoming 127 Hours – also getting its premiere at the LFF – show him developing into a much more interesting actor.

Physically he’s the spitting image of the young Ginsberg and the voice is uncannily like the recordings from the period. But he also catches Ginsberg’s nervous energy, his questing intelligence and his desire to create the best and truest art he can, even if this means digging into the most painful memories of his past. The scenes where he performs the poem aloud, overcoming initial nervousness to create an impassioned, symphonic combination of prayer, cry of pain and verbal jazz solo, are worth the price of admission alone. In fact, the weakest parts of the film for me are the animations. Technically proficient and occasionally right on the money – especially in the poem’s ‘Moloch’ section, where the US military/industrial complex is transformed into a devouring, satanic presence – the images are more often ploddingly literal and the ‘stick figure’ characters give it the somewhat disconcerting look of an X-rated Lloyd’s Bank ‘for the journey’ commercial.

But that’s a minor quibble. For the most part, the film reclaims Howl from the academic bookshelves and catches the nature of its genius – often explicit, frequently brutal but always heartfelt, challenging and deeply humane. Great poetry, indeed. And pretty good cinema as well.

Reviewed on: 11 Oct 2010