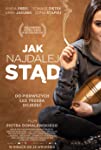

Eye For Film >> Movies >> I Never Cry (2020) Film Review

I Never Cry

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

Piotr Domalewski touched on the impact of migrant working on Polish families in his debut Silent Night, which had a protagonist who travelled home from his job in the Netherlands and the writer/director returns to the theme in more detail for his follow-up to show how economic necessity can drive a wedge through families.

This time around, the tale is told from the perspective of those who have been left behind, chiefly Ola (Zofia Stafiej) a self-possessed 17-year-old and the daughter of the migrant worker in question, a father who won't ever be coming home for Christmas again after he dies in a workplace accident in Ireland. Before we hear about his fate - revealed in the film's early stages - we learn that Ola's relationship with him has become largely transactional, with the main focus for her being the car he has promised her if she passes her driving test. His death is revealed bluntly from a distance and Ola finds herself tasked by her mother with trying to bring home his body, not just because the teenager speaks English but because her mum needs to stay home and look after her disabled brother. Ola's personal driver is that potential car fund - something she feels her father owes her for everything he has put her through - which becomes her focus.

Domalewski has proven his ability with family relationships before and economically sets up the mother/daughter/brother dynamic, showing how even though there are tensions - particularly over money - they are a unit who pull together when they need to. Before long, Ola is on her first plane journey, armed with a small amount of cash, a pack of cigarettes - the cost of which in Ireland becomes a repeated source of dry humour - and a lot of determination.

The title of the film itself - which does, indeed crop up as a line of dialogue - suggests the combination of chief emotions of denial and stoicism that Ola vacillates between for much of the film. She soon finds she has to rely on the latter quality, as her attempts to get her dad home are fraught with difficulty. There's the expense of transporting the body, big question marks over how he came to die in the first place and, front and centre, Ola's own odyssey into her father's life as she finds out about him for the first time.

Domalewski's first film was loaded with tension and his second comes weighted with grief, although he employs similar observational humour to stop things getting bogged down. Mostly shot with social realism to the fore, Domalewski's decision to include just about every obstacle for Ola he can, along with a nicely shot but not entirely plausible encounter with a group of locals who take her on a drinking spree, makes the film feel overloaded with incident in places, when more time spent unpicking Ola's emotional journey would be more interesting.

The personal is prominent, with Domalewski leaving the viewer to draw their own picture of the broader socio-economic failings of all this. Instead, he focuses on Ola's experience, as she discovers the man she barely knew, drinking his liquor and smoking his cigarettes while trying to work out what made him tick and cope with the experience of a sort of "double grief" both for the father she imagined she has lost and the one that now takes firmer shape as she speaks to those who knew him better than she did. Domalewski continues to mark himself out as a director to watch from Poland, tackling contemporary issues with care and flare.

Reviewed on: 09 Jul 2021