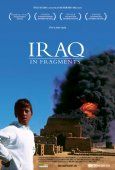

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Iraq In Fragments (2006) Film Review

At a time when a Western journalist would not be seen alive outside the green zone in Baghdad, James Longley has made this film. That is an accomplishment in itself. He avoids a narrative commentary, in favour of people’s voices, often children, and does not tell a story so much as observe and record.

If anyone thinks George Bush’s latest push for victory – whatever that means – is going to work, should listen to what these ordinary Iraqis are saying.

“For 35 years Saddam took everything. Now the Americans are worse.”

“They came to support us and turned against us. The problem is they only know how to use force.”

“Now the war is over, everything in Iraq is controlled by America.”

“It is impossible to change us with the barrel of a tank.”

Eleven-year-old Mohammed says, “It was so beautiful. Now there is nothing. The world is so scary.”

The film is in three parts, representing the factions in this unofficial civil conflict, although Longley is not concerned with war, rather the casualties of hope. You see smoke from explosions in the distance and helicopters low over buildings and heavily armed young Americans in a Jeep, grinning at the camera, and alcohol sellers in the market being beaten up. But most of all, you see people going about their daily lives, wanting the foreign forces out (“Why don’t they take the oil and leave us alone”) and a new partitioned Iraq emerging in its own way (“What America promised was all lies. Where is the democracy?”). No one has a good word for Nouri al-Maliki and what they call “imposed government.” The bloody hand of US imperialism, linked to oil, stains Iraqi sensibilities and they want to be cleansed of it.

Mohammed’s story is of a boy, living without a father, working in a backstreet mechanic’s shed, reluctantly going to school where, after five years, he still can’t read or write, fearful of a future in which the poor will remain poor and only the rich benefit from any reconstruction money.

The middle section in Sadr City is the strongest, because it is here where religion and war are being soldered. Feelings against what they call “the invaders” are fierce (“We want to close every door of depravity opened by the Americans”). The streets are full of chanting, marching men. A peaceful demo ends with Spanish troops (can this be right? I thought Spain pulled their soldiers out) opening fire. The dead and wounded are rushed away and later coffins are carried through the city, followed by an angry crowd, whipped up by the rhetoric of religious leaders. The mood on these streets is dangerous (“There is one God. America is the enemy of God”).

The final section is called Kurdish Spring and has a gentler, softer feel to it. Two boys are best friends, living in the country, close to a village school. “I want to go to college and be someone,” the eldest says. But it is not easy. “I work the brick ovens and then I tend the sheep,” he says. His father is old now and spends his time “with God.” Because there is no evidence of coalition forces in this area, the ending of Saddam brutal regime is appreciated.

The film has no opinion and is dispassionate. In the Baghdad sections, you are not aware that 90 people are being killed every day and electricity is a bonus, rarely enjoyed, and “Saddam would never have allowed this situation.” When you see a policeman directing traffic, you don’t wonder at the amount of cars in a city that is not supposed to be functioning, you think, “How long before he gets shot?” By showing ordinary life at an extraordinary time, Longley opens our eyes to humanity’s ability to normalize abnormality, which is difficult when a group of men are talking about a brother and sister who were shot and killed on the street last evening by American soldiers for not stopping when ordered.

And the old men are still drinking sweet tea and playing backgammon.

Reviewed on: 18 Jan 2007If you like this, try:

Ghosts Of Abu GhraibMy Country, My Country

Queer Fear: Gay Life, Gay Death In Iraq