Eye For Film >> Movies >> Killing Patient Zero (2019) Film Review

Killing Patient Zero

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Ask the average American how the AIDS epidemic reached the US and the chances are that, if they try to answer at all, they'll mention Patient Zero. Ever since the release of Randy Shilts' 1987 book And The Band Played On, this monstrous figure has loomed large in the popular imagination - but the truth is, no such individual ever existed. The very term 'patient zero' arose from a misunderstanding, though it is now used frequently to refer to what epidemiologists call an 'index case', the first documented case of an epidemic disease within a specific population. Nobody knows how AIDS got to the US. What we do know is the Gaëtan Dugas didn't cause it.

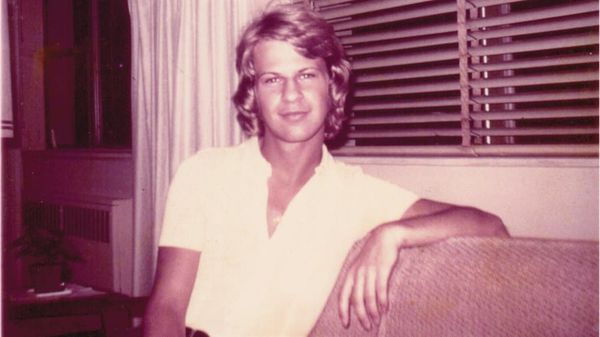

Dugas was the man demonised in Shilts' book, a French Canadian airline steward whose work carried him back and forth across the North American continent and between most of its major cities. He was described as a man who knew all along that he was infected, didn't care if his actions led to the deaths of others, and had an astounding amount of sex. According to the friends, colleagues and medical acquaintances who testify in this documentary, only the last part was true.

How did Gaëtan come to be so visible among so many infected people? It was, a medical researcher explains, because he was so keen to help by providing details of his sexual history, blood samples, anything he could to try to assist those who were trying to make sense of the strange new affliction that was killing gay men. He didn't adopt safer sex practices because, back then, no-one knew for sure if they would make any difference. Watching this today one cannot help but think of all the people who refuse to be inconvenienced by wearing masks to prevent Covid-19 transmission even though there's much better evidence for that than anyone had about condoms in the early days of AIDS.

Writer/director Laurie Lynd does a good job of bridging the gap between LGBTQ and straight audiences by explaining why gay men were disinclined to listen, at first, to doctors and scientists - the same groups of people who, not long before, were describing them as perverts or as mentally ill, institutionalising them, prescribing quack 'cures' like electric shocks and contributing to their social exclusion. There's also some discussion here of the importance of sex as a form of pleasure in lives deliberately deprived of many of the pleasures others take for granted.

The early years of the AIDS epidemic remain a deeply traumatic subject for most of those touched by it in their own lives, and that pain echoes throughout this film. Where it focuses on history, however, the film is on well-trodden territory and doesn't deliver much that stands out - others have told that part of the story better. Its strength is in its focus on Gaëtan's personal story and those that intersected with it. It aims to redeem his memory and to celebrate the person he really was. Thus recast, he emerges as human, vulnerable and sometimes mistaken, but also as a radical figure in his refusal to succumb to the pressures of the world. He is remembered as somebody who saw no need to apologise for his sexuality or his existence but lived loudly, exuberantly, bringing joy to those around him - a man whose promiscuity stemmed from his itinerant lifestyle rather than any lack of care for his partners, and who was not unusual in his choices, just good looking enough to have a lot of options.

The importance of Shilts' book is recognised here - the impact it had on the political classes and the contribution it made to turning the tide. Its treatment of Gaëtan made it visible, but Lynd will not let us forget the human cost. That his family have chosen not to participate here, having long ago been advised that they would be better off staying silent, leaves their suffering to the viewer's imagination. We know only that they loved him and never bought into the monstering.

There are, of course, lessons here for how we think about the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as reflections on the sometimes devastating power of the media, both for good and ill. Most of all, there's a plea for us to resist easy narratives that mean we lose sight of others' humanity.

Reviewed on: 22 Oct 2020