Eye For Film >> Movies >> Lord Of Misrule (2023) Film Review

Lord Of Misrule

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

In its early days as a cinematic genre, folk horror was a means of exploring the monstrous other, the threats to Christian civilisation which lingered in neglected places. Times have changed, however, and even when, as is the case here, films stick closely to formula, context alters the message. In 2024, neo-Paganism is thriving and society at large no longer looks at surviving ancient Pagan customs in a hostile or defensive way. Although evangelical Christianity is also on the rise, it has become much more rare to see films addressing the sort of pastoral Christianity which only a few decades ago was thought of as the default. The Lord of Misrule and his enemy, Gallow Gog, seem perfectly at home in this film. It’s the vicar who finds herself on their territory who is the more exotic character.

We meet her – Rebecca (Tuppence Middleton) – in the mostly empty church where she is carrying out a baptism. Outside, her daughter, Grace, golden haired and wearing feathery angel wings, is left to her own devices. She sees three small figures in cowls and animal masks standing in an adjacent field. Whether or not they are real is uncertain, but we will see them again. Perhaps acting under some malign influence, she prepares to do violence to pet rabbit Bunbun, but there’s a little more realism at work here than is common in such tales, and Bunbun isn’t taking any shit.

The rabbit is worthy of notice. Very alert and engaged, paying attention, and not the least intimidated in situations where most would panic. If only the rest of the cast were that invested. As the plot develops in by-the-numbers fashion, there’s a lack of texture to the performances which means viewers have little to hold onto. A folk festival in the village (which Rebecca and family have only recently moved to) is colourful and entertaining as its sets up the film’s mythology, but when Grace goes missing, last seen running into the woods emitting mischievous, tinkling laughter, Middleton fails to convince emotionally. She isn’t helped by a script which pays lip service to terrified, grieving parent and plunges headlong into mystery solving mode.

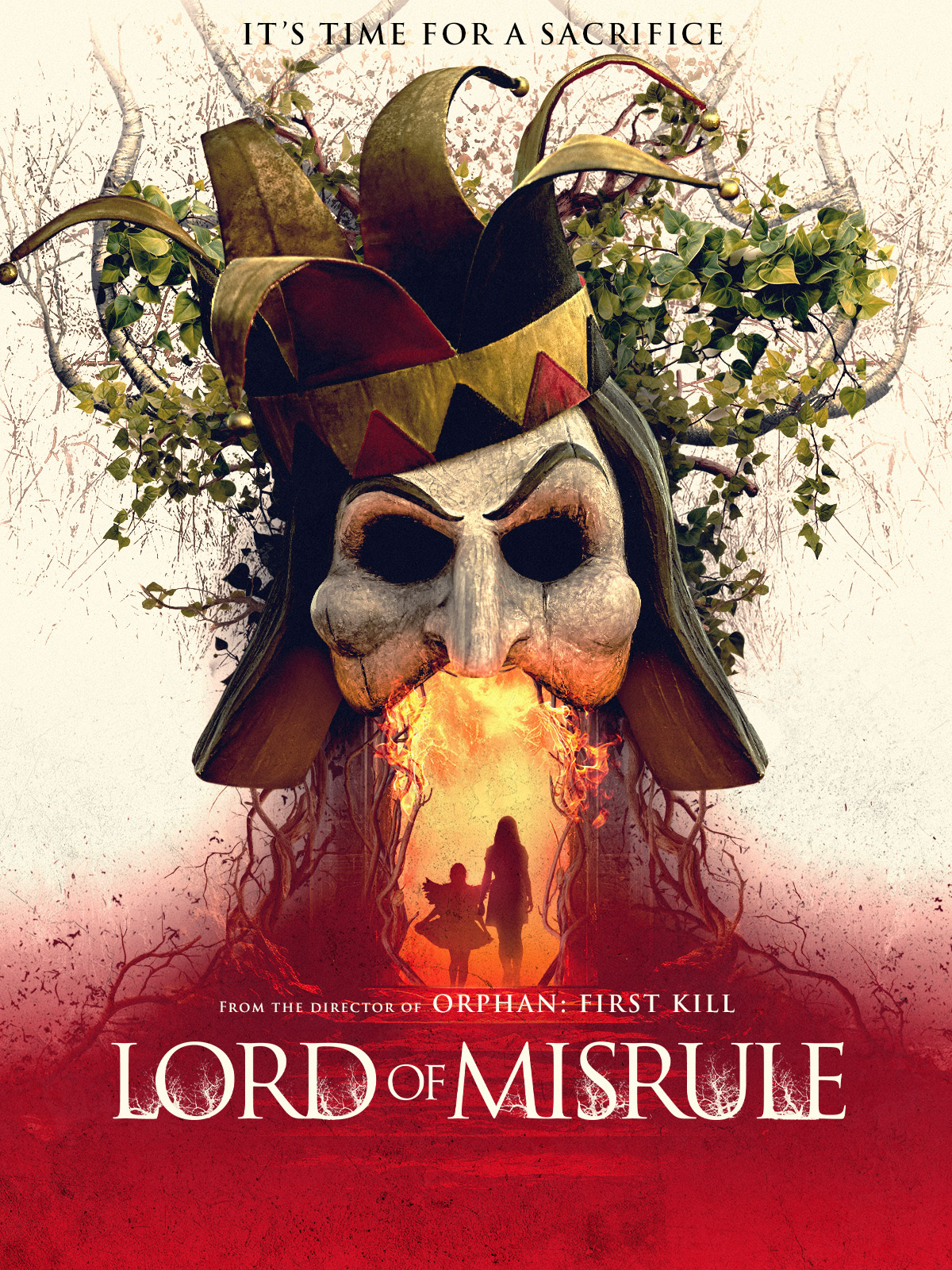

This is a genre which depends heavily on production design, and Alison Butler does good work in that regard, though she’s up against it, with many bare trees visible despite the fact that it’s supposed to be harvest time. The film’s creature design is rather clichéd but the detail work elsewhere shines, in part because Butler has resisted the temptation to cobble together bits and pieces from all sorts of different mythologies, as others have done in her place, and has instead developed threads which help to ground the story when the mystery is finally revealed. It seems appropriate that her work features heavily in the pre-credits sequence. Away from the Pagan trappings, she creates interiors which feel lived-in and round out characters where the script falls short.

“He stands in the fields and waits,” state various villagers with irritating obscurity as Rebecca tries to figure out what has happened to her child. The phrase “All is as was” also turns up repeatedly, with something of the portentous pointlessness of “Take back control.” Curiously, we never see Rebecca asking her god for help. Her rediscovery of faith comes late in the day, and takes an unlikely form which itself feels like a comment on the genre’s history. This delivers the film’s one interesting idea: that faith has a power of its own, perhaps irrespective of where it is focused. Whilst understandable that this would be saved for the finale, it’s a shame we don’t get to it earlier, because the rest of what we get here is far too familiar. it will satisfy some genre fans who simply want more of what they know they like, but is likely to leave others with doubts.

Reviewed on: 07 Jan 2024