Eye For Film >> Movies >> Love And Pop (1998) Film Review

Love And Pop

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

At 16, Hiromi (Asumi Miwa) is caught between the childish experience of life as a passive observer and a new drive to find agency. She drifts around wondering what to do with her future, outwardly supportive but inwardly dismayed by her three best friends’ seeming readiness to seize opportunities, by their apparently clear sense of purpose. When, in a Shibuya mall, she finds a beautiful topaz ring on sale for just one day, she becomes determined to buy it – not to depend on help from other people, but to make the money for herself and achieve her objective. it’s a bold leap into an adult way of thinking, but is it something that she’s ready for?

How does a 16-year-old girl make the equivalent of £130 in one day? Hiromi doesn’t have a job. There are other options, however. In an early scene, we see her pursued across a bust intersection by a thirtysomething man who offers to pay her to go an eat lunch with him. She’s wearing her school uniform and he’s loud and pushy, but none of the many passers-by moves to intervene. She ignores him with such steely calm that it’s clear she’s had to put up with this sort of thing before. In fact, in that time and place, the man has a reasonable chance of finding a schoolgirl who will accede to his request. Despite a change in the law, with politicians gradually treating the matter more seriously, enjo kōsai – a term translated here as sugar dating but more commonly known as compensated dating, specifically between older men and teenagers or very young women – still goes on today.

Sometimes, it’s harmless. We see Hiromi agree to dates, all taking place in the daytime, with men who just seem to want company and attention. One tells them that he has a daughter their age, and delights in the chance to give life advice. Another wants somebody to appreciate his culinary abilities. There is a long tradition in Japan of men paying women to show them respect and appreciation, pour them drinks and laugh at their jokes. Hiromi and her friends roll their eyes afterwards but come out unscathed. Adjacent to this, however, is a much more dangerous world, and it’s difficult – especially for someone so young – to tell the difference between the two.

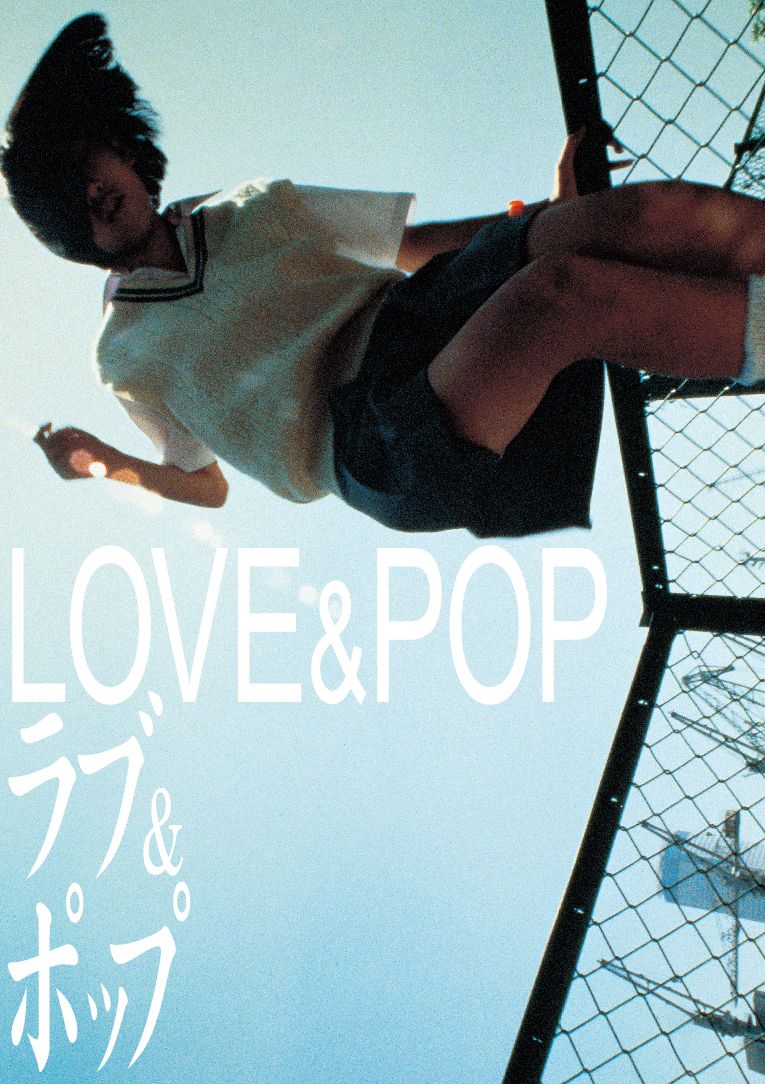

First released in 1998 and a screening as a retrospective at Fantasia 2024, Love And Pop is an experimental piece of work, as striking in its stylistic choices as in its subject matter. In an early scene, we see Hiromi and her family seated around the breakfast table from the perspective of somebody inside their microwave oven. Later we will look through a plate as a spoon slams down upon it, watch a man drinking through the bottom of his glass, and so on. This approach is highly distracting at first, but over time you will find yourself settling into it. It has the effect of bringing older viewers closer to Hiromi’s perspective, inviting us to look on life as a strange and unpredictable thing which we’re not yet sure how to interpret; a mixture of the intriguing, the ugly and the absurd.

Despite being written and directed by men (it’s based on a book by Ryū Murakami), the film does an impressive job of bringing us close to its young female protagonists, and never more so than when showing us their appreciation of the absurd. In its early stages, before Hiromi’s thoughts come to be dominated by adult acquisitiveness, it’s full of scenes in which they hang around the streets laughing, expressing their disappointment in their boyfriends and sharing odd bits of news. Director Hideaki Anno’s camera works to create a sense of space around them even in crowded places. Later, it zooms out when Hiromi has space to make decisions, moving in close and showing us only parts of her when she has least control. There are a few early shots looking up her skirt which are disconcerting, but Anno is careful not to show more than a glimpse of thigh. He’s deliberately reflecting the style in which schoolgirls are presented in anime, inviting viewers to feel reassured by that fantasy space, before reminding us of the ugliness that the fetishisation of girls this age leads to in reality.

Coming of age, for Hiromi, involves looking that ugliness full in the face for the first time. The fantasies of men looking for dates, recorded on a telephone message service. The titles of pornographic videos. Her own inability to know who she can trust. Her initial sense of power – which might be real when she’s in company, and cautious – gives way, when she’s alone, to an awareness that she’s surrounded by potential predators, with nobody else showing the slightest interest in helping her. She will be blamed for her predicament, and not everyone watching the film will take away the same message, yet Miwa’s intense, very present performance makes it impossible not to feel for her and respect her resilience. Despite all the drama, the horror and the strangeness of the film, what comes through most clearly and importantly is her humanity.

Reviewed on: 19 Jul 2024