Eye For Film >> Movies >> Manderlay (2005) Film Review

Manderlay

Reviewed by: Anton Bitel

When Lars von Trier's bitter Brechtian experiment Dogville (2003) first screened at Cannes, he incurred the righteous wrath of critics from the US, all of whom lined up to accuse him of being "anti-American" and "arrogant". Most of the anger seemed directed not so much at what Dogville had to say (about power, corruption, exploitation and Old Testament vengeance in a small border town during the Great Depression), but rather at the supposed presumptuousness of an outsider offering comment on America in the first place.

To judge by Manderlay, the second film in von Trier's projected American trilogy, the maverick director remains undeterred and has no intention of holding back in his self-appointed role of agent provocateur. This time he has tackled head on an issue from which even most American insiders shy, namely race relations and the lasting legacy of slavery. The result is an incendiary fable with something to challenge, stimulate, or even offend, everyone. Be warned: this Great Dane backs up his satiric bark with a vicious bite.

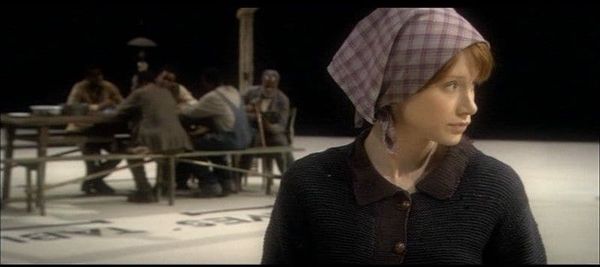

It is 1933. Driving, and constantly arguing, with her gangster father (Willem Dafoe) through the American South, idealistic young Grace (Bryce Dallas Howard, taking over confidently from Nicole Kidman) stops for lunch outside the gates of a plantation, called Manderlay, just as a young black worker, Timothy (Isaach de Bankole), is about to receive a whipping. Grace realises that this is a place where slavery has never ended and so, armed with good intentions (and four of her father's gun-toting henchmen for back up), decides to liberate the community of black labourers and see them through to their next harvest, teaching them a few lessons in democracy along the way.

Shortly after Grace's intervention, Manderlay's elderly white matriarch (Lauren Bacall) dies, leaving behind a going concern and a handwritten instruction manual, known as Mam's Law, that Grace refuses on principle to consult. Yet Grace's "pupils" show a disheartening reluctance to take advantage of their liberty and, as one disaster after another buffets the new free enterprise of Manderlay, only old Wilhelm (Danny Glover) seems to recognise the crucial role that Grace has to play in its future - a future that is, after all, not so very different from its past.

Despite its beautifully minimalist sets, drawn in chalk on a sparse soundstage, its division into eight neatly headed chapters and use of an omniscient narrator (voiced once again with sardonic venom by John Hurt), Manderlay is no fairytale with a happy ending, rather an uncomfortable allegory of the many insidious guises that enslavement can adopt, including colonialism, economic subjugation, and, most provocatively, democracy itself.

With its inchoate mise-en-scene, the film offers a staging area for ideas, where everything from the inveterate social problems of African-Americans to the "liberation" of Iraq can be played out in a form that resembles that most political of dramatic genres, Greek tragedy. Whether Grace is regarded as embodying the values of interfering do-gooder liberalism, or Bush's neo-con paternalism - she seems, paradoxically, to represent both - the flaw that dogs her and all the characters in this film is human nature itself, of which von Trier takes a deliciously dim view.

Neither Grace, nor Wilhelm, nor Timothy, nor anyone else can help being who they are, regardless of how they became that way and the utopia of Manderlay is doomed to remain an elusive fantasy so long as its inhabitants keep having one kind of paradise, or another imposed upon them.

Like Dogville before it, Manderlay culminates in a photomontage of poverty, exclusion and violence, all to the ironically upbeat accompaniment of David Bowie's Young Americans. Yet it would be simplistic in the extreme to dismiss either film as simply "anti-American". Von Trier is all too aware of how his own native country profited from the slave trade and what the director regards as supremely wrong with the state of the world's current superpower, he would no doubt concede is equally rotten, albeit on a smaller scale, even in the state of Denmark.

Manderlay, you see, is a place that we all inhabit, which poses problems that the whole world must either try, like Grace, to face, or else, like her criminal and criminally cynical father, ignore. Von Trier is not, despite what his critics say, so "arrogant" as to suggest a solution, but he does highlight painfully difficult questions with great intelligence and clarity, as well as a prankster's dark wit. Most filmmakers achieve far less.

Reviewed on: 15 Feb 2006