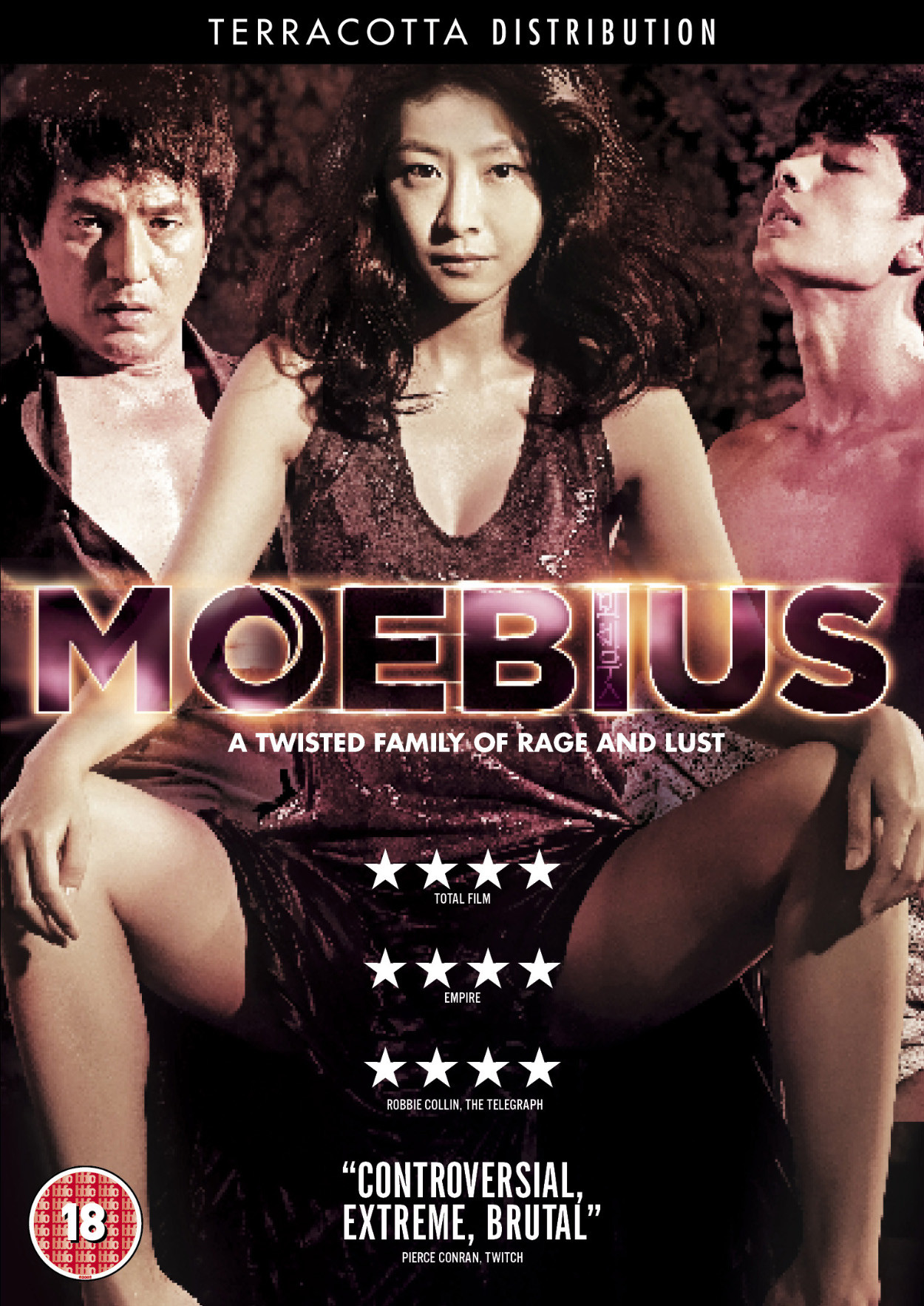

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Moebius (2013) Film Review

Kim Ki-duk films are an acquired taste. This one features intense sexual violence right from the outset. It's not gratuitous, in that it's absolutely integral to the plot and we never see more than we need to, but many viewers will find it gruelling nonetheless.

Kim's films have always been short on dialogue. In this one, though some information is conveyed in text (English but plainly not written by a naive speaker), not one word is spoken. There's no need for dialogue. Its absence helps to strip away any the veneer of civilisation. These are people who wear neat clothes, live in a clean house and drive clean cars, but their actions are intrinsically animal; there is nothing in the mechanics of their interaction that could not have been played out the same way in Neolithic times.

The film opens with a fight between a mother and father as their son looks on. The mother is upset - visibly in pain - because the father is having an affair with a younger woman. It's a familiar enough story, but here things go further. Having seen the father and the young woman together, later that evening, the mother decides to take revenge. Using a sinkal, or divine knife (kept beneath the family's bust of the Buddha), she attempts to cut ff the father's genitals. Thwarted and locked out of the room, she instead takes out her fury on the son, whose masculine sexuality seems to cause her additional distress. One sharp cut and all their lives are changed forever.

This is Freudian drama at its most extreme, and one wonders if Freud would have had the stomach to watch throughout; yet despite the theatricality of it, the complex performances Kim elicits from his four central players maintain an atmosphere of real emotional force and let us see them as individual human beings.

As the plot grows more complex, several themes begin to emerge. Male and female characters define their identities in opposition to one another, with a focus on the phallus versus its absence (which may explain the complete elision of anal sex as an option when alternative methods of male orgasm are being explored). The social value placed on the phallus becomes acutely apparent as the son becomes a target of abuse by his former peers, of general mockery and later of attempted gang rape. The nature of fatherhood is explored as the father who used to ignore his son finds himself willing to do anything to help him. As the physical, sensory relationship between sex and pain is explored, we also find ourselves confronted by the relationship between suffering and desire or emotional pleasure; despite the brutality on display (most of it non-consensual), this is ultimately a story more focused on masochism than on sadism.

Intensely erotic throughout, even in the absence of what most people would think of as sexual, this feels like the culmination of a number of threads that have run throughout Kim's work, from the moral and emotional boundary-blurring of Bad Guy to the interrelation of sexual violence and penance in The Isle. It's easy to imagine it being performed as opera, yet the mundane locations in which it is set remind us that this heightened drama isn't very far removed from real life. The fragile boundary between reason and instinct can only take so much pressure, with one violent act all it takes to send things careening out of control. The alternative, Kim seems to suggest, lies in spiritual focus, but perhaps that's just another side of the same cycle.

Reviewed on: 25 Sep 2014