Eye For Film >> Movies >> Mountains May Depart (2015) Film Review

Mountains May Depart

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

It's 1999 - the dawn of the new millenium is fast approaching and in Shanghai, as elsewhere, everybody is excited by the prospect of a bright new future. Tao (Tao Zhao, wife of the director) is a leader of celebrations, a dance teacher. The film opens with a rehearsal of one of her musical numbers, a troupe of Chinese people marching enthusiastically to the tune of the Pet Shop Boys' Go West. The West seems to symbolise the modernisation that everyone is pursuing, from Liangzi (Jing Dong Liang), who mines the coal that powers the factories and cities, to Zhang (Yi Zhang), who drives a red Volkswagen and boasts about his business plans.

Tao is close to Liangzi. Perhaps she loves him, but he doesn't have a big red car or the security promised by wealth. Zhang lurches between petulance and aggression, feeling entitled to her love just because he desires her, but she understands the opportunity he represents. For all her joy, all her exuberance, she's drawn to materialistic thinking, already entering into the true spirit of the age.

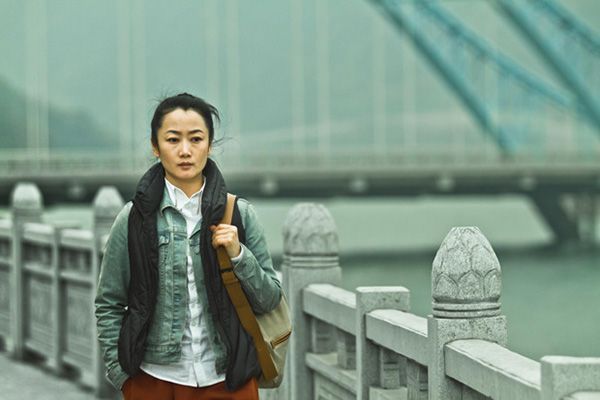

Mountains May Depart is divided into three parts (each in a broader aspect ratio than the last), revisiting these characters in 2014 and 2025 as their lives change in unexpected ways. It hinges on a strong, troubling performance by Tao Zhao. Even in the final segment, where she's absent until the last scene, her presence looms large. Here her son, living far away, struggles to remember her as his generation will struggle to remember the old China and the choices it had at this pivotal time. Struggling to communicate with his father, the young man represents everything his parents' generation longed for and much that they cannot abide.

Outside Tao's sphere of influence, Zhangke Jia is more interested in developing his setting than his characters. Small objects follow us through the film, sets of keys taking on multiple layers of meaning. A plane comes crashing into one scene as if it has escaped from the work of John Irving, serving no immediately discernible narrative purpose, but like the caged tiger in another scene or the half-dry river basin in a third, it hints at external forces altogether beyond our heroes' control. Coal piled too high in a truck threatens to topple it over - the load might have been balanced more wisely but this, too, seems inevitable, as if individuals have lost the wit to control their actions in the face of industrial pressures. In the middle section, as Tao ponders the fate of her son, his disappearance with his father seems to be a fait accompli; she cannot imagine another way, cannot truly believe in her own agency. Zhng, meanwhile, sets himself up as possessed of a destiny which gradually disempowers him.

A bold study of what it means to be Chinese in the modern age, Mountains May Depart explores the monumental through the personal, the intimate. If it's bleak overall, it also suggests that the future isn't something we can hope, from here, to understand.

Reviewed on: 05 Feb 2016