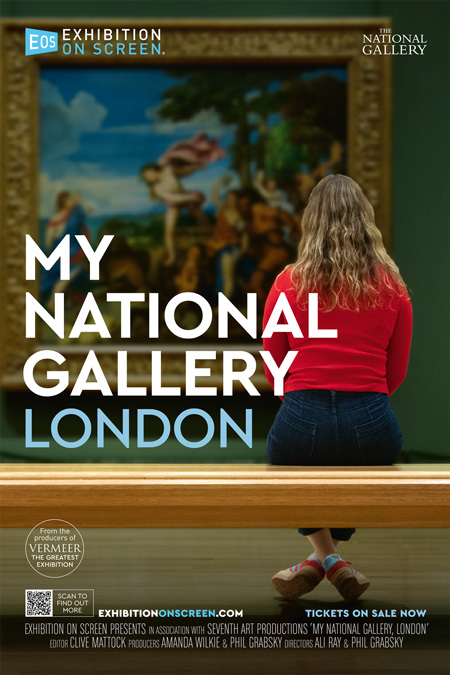

Eye For Film >> Movies >> My National Gallery (2024) Film Review

My National Gallery

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

In most parts of the world it is not possible to see an Old Master, or even a famous modern painting, without a lengthy journey. Even if you’re lucky enough to live in a city with an impressive collection of art, the chances are that you’ll have to pay to see it. In the UK, things are different, and yet many people take access to art for granted, whilst others don’t realise that it’s there at all, or don’t think of it as something for people like them. My National Gallery, part of the Exhibition On Screen series, looks at what London’s most famous collection means to visitors, how it was created and how people from all walks of life have been influenced by it.

Some of these stories come from people who work there – but not just those at the top. We meet cleaners, security guards, tour guides, people who work in the gift shop. They talk about the first connections they formed with the gallery, its personal significance for them, and their favourite paintings. The range of these is considerable – even if you visit the place frequently yourself, the chances are that you’ll discover something you didn’t know was there, as well as finding new ways of relating to familiar works.

The reasons who these pictures appeal are many and varied. A woman talks about her fascination with the hidden codes in Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors. Another reflects on the way that Degas’ The Ballet Dancers makes her remember her own childhood ballet lessons and the pain in her feet, as well as her love for her nan, who also considers it a favourite and reflects on how it creates a sense of movement. Still another speaks of her love for the monsters in Salvator Rosa’s Witches At Their Incantations. A man remembers how he was first drawn to Bruegel the Elder’s The Adoration Of The Kings because the dilapidated building at its heart reminded him of his hometown of Hull.

Lest viewers tire of hearing the views of ordinary people, there are a few celebrity opinions thrown in there too. Incorrigible trainspotter Michael Palin waxes lyrical about Turner’s Rain, Steam Speed, about the birth of the railway and looking to the future, “his sort of science fiction painting.” Claudia Winkleman admits to liking the big hitters, choosing Virgin Of The Rocks by Leonardo Da Vinci. Terry Gilliam recalls how the gallery inspired his Monty Python art, highlighting Allegory Of Venus, Cupid And Folly, by Bronzino, which he interprets as a story about syphilis, and revealing the origins of the Monty Python foot.

Mixed in with the celebration, there is necessary criticism. A security guard talks about how he fell in love with the paintings after getting a job there, picking Caravaggio’s Supper At Emmaus as his favourite, for its conversational quality and sense of wonder at the resurrected Jesus , but noting that he doesn’t really feel represented by a collection that is almost exclusively about white people. Others discuss the shortage of paintings by women, and the way that influences what we see of women.

Both these things are artefacts of the era during which most of the paintings were collected. A curator discusses efforts to keep it up to date by moving things around, and his own fondness for Melchior d’Hondecoeter’s Birds, Butterflies And A Frog Among Plants And Fungi, which, at the time of filming, was languishing in the basement. The artistic value of diversity is established by a BSL tour guide who discusses the different way that he thinks Deaf people notice things in paintings. he also reflects on his love of Pietro Longhi’s Exhibition Of A Rhinoceros In Venice and his empathy for its animal subject, Clara, in light of have experienced objectification himself.

The focus on one painting after another can get a bit samey, but it’s interwoven with the story of the gallery’s origins and development over time, which is consistently intriguing. There’s a look at its early days in Pall Mall when paintings were exhibited in rooms designed to be residential, crowded together in a fashion reminiscent of the Salon de Paris. We see the evolution of the gallery from a place where paintings were donated to one much more actively involved in collecting, especially during the frantic effort to ‘save’ historic treasures from predatory Americans, and the consequent shift to a tax-funded model. Then there was the Blitz, during which paintings were famously secured in a Welsh slate mine – but each of these stories has a twist, and is full of fascinating details.

As the gallery has changed, so have its visitors. What this documentary achieves most successfully is to complement its mission of making art available to the masses. It emphasises that you don’t need to come from a particular background in order to have strong feelings and intelligent things to say about paintings, or in order to feel a connection to them. It creates its own connection to gallery regulars, whilst reaching out to invite others to experience it for themselves.

Reviewed on: 03 Jun 2024If you like this, try:

Canaletto And The Art Of VeniceJohn Singer Sargent: Fashion And Swagger

Tokyo Stories