Eye For Film >> Movies >> Peafowl (2022) Film Review

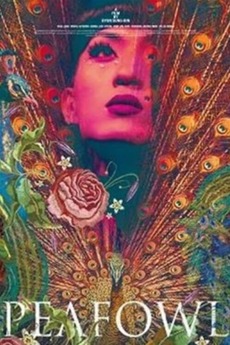

Peafowl

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

One of the most challenging things to do as an actor – especially when one knows how many audience members will fail to recognise it – is to perform something badly. Peafowl opens with a dance contest in which trans heroine Myung (Choi Hae-jun) is hoping to win money for surgery. Her moves are good from a technical perspective, but anyone can see that there’s something missing. She doesn’t understand where she’s falling short, so afterwards a judge explains it to her. It’s that it’s so impersonal. There is nothing there to make it distinctive, to tell us who she is.

It’s a strong opening to a film focused on identity, rootedness and the process of building oneself into a complete adult human being. Myung’s gender is not part of her internal conflict but, perhaps, its social impact is. She has been cut off from her family and all the complex legacy of her rural upbringing. Somewhere in that trauma, she missed out on the normal process of growing up and finding a way to fit into the world. As a dancer, she has spent her adult life trying to do and be what other people want. When, on the night of the contest, she gets the news that her father has died, she knows that going back home will be almost unbearable, but viewers may correctly suspect that it’s an opportunity for her to get a firmer grip on her own identity.

Transphobia rears its ugly head almost as soon as Myung reaches her destination. It comes, primarily, from her uncle Uk-do, who, as the brother of the dead man, has a strong say in how the customs surrounding his death are to be carried out. His wife is overjoyed to see Myung again, but the support she gave her in childhood now manifests as a mixture of guilt and affection. When the couple’s son, Bo-suk (Go Jae-hyun), confides in Myung, the stage is set for a fresh round of troubles which will push the family towards breaking point.

Ancestry carries a lot of weight in traditional Korean society and Peafowl gradually unfolds as a story of generational trauma, with Uk-do and the deceased father gradually revealed to have been damaged by bullying and exclusion themselves. The village is full of secrets, and it’s not so much Myung’s transition as her comfort with it which causes shock. Indeed, the fact that she’s so sure of herself inclines many of the villagers simply to accept her as a woman when Uk-do isn’t there to protest. Her childhood friend Woo-gi (Kim Woo-kyum) never doubts her, and functions as a conduit for modern values in a village where little has changed over the past two centuries. This isn’t just another film in which modernity is placed in opposition to the past, however. Myung will need to find a way to reconcile the two if she is to find a way forward for herself and, in the process, help the villagers to move beyond a history of social self-harm.

The peafowl is an interesting choice of motif, males being glamorous whilst females are drab and brown. In Korea, it has traditionally been a symbol of patriarchal authority. The film’s original title, Gongjakseon, translates literally as ‘peacock fan’, referring to a traditional item used exclusively to cool the country’s monarch. It’s an interesting choice for a film in which a peacock features in a dream and power shifts significantly over time. Because of the funeral, ritual trappings are everywhere, and they function as symbols of a wider system of power, their subversion a means of taking ownership of social space.

There’s a lot of interesting work here and it’s startling to realise that it’s director Byun Sung-bin’s first venture into features. It’s not just the set-pieces which make an impression, such as Myung screaming on the dancefloor at the news of her father’s passing when the music is too loud for us to hear her at all, but the confidence with which Byun handles quieter and more esoteric moments, finding a way into the rhythms of the village. These stand in stark contrast to those of city life and the interactions of those who have lived it or long for it. The natural world, perceived as full of signs and portents, has a vital role to play, reminding us of the larger cycles of time and experience within which family dramas play out.

Screened as part of Queer East 2023, Peafowl reminds us of the larger cost of social exclusion, to all involved, and of the ways in which acknowledging and adapting to lived realities can enrich traditions and allow them to flower.

Reviewed on: 22 Apr 2023