Eye For Film >> Movies >> Pharma Bro (2021) Film Review

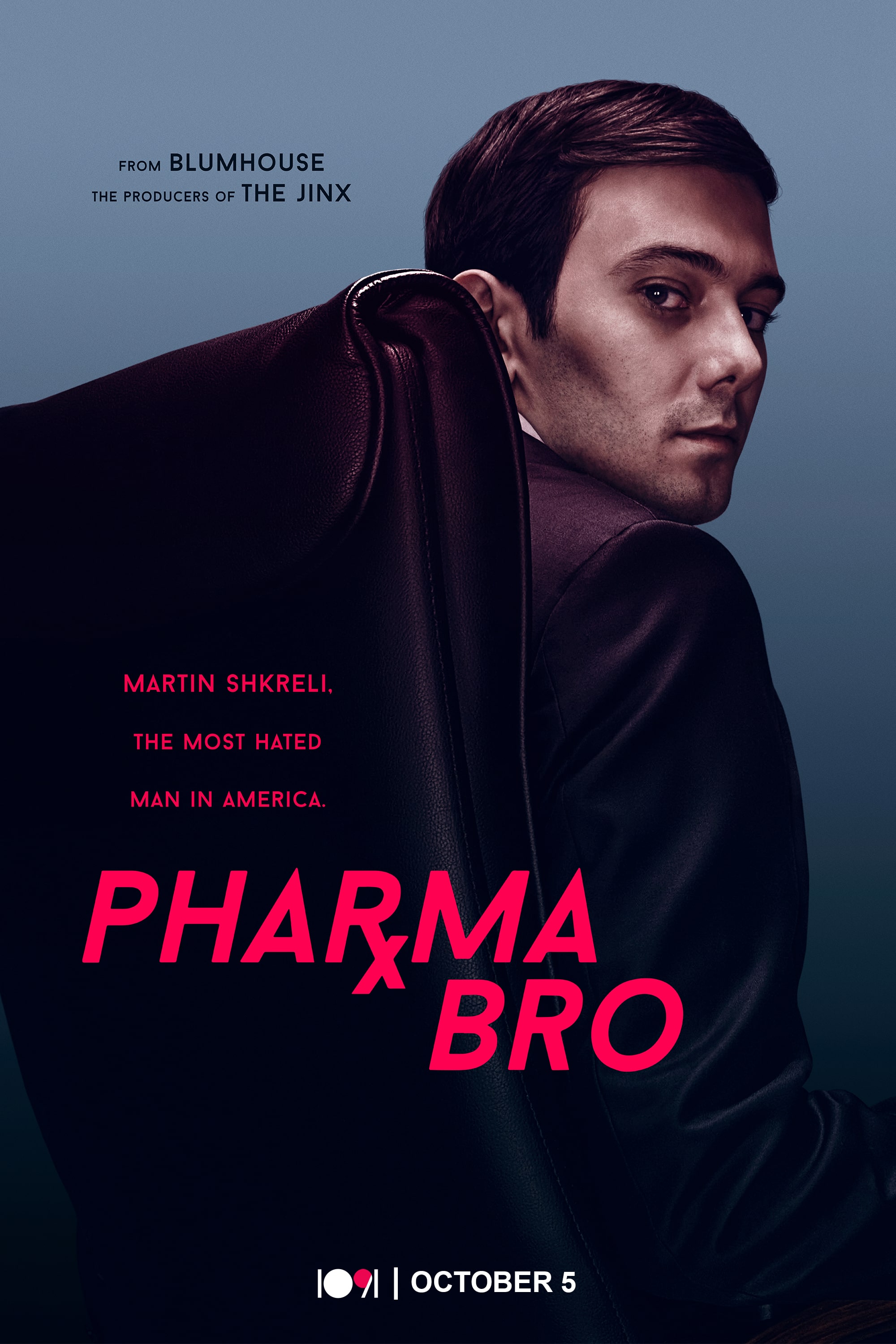

Pharma Bro

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

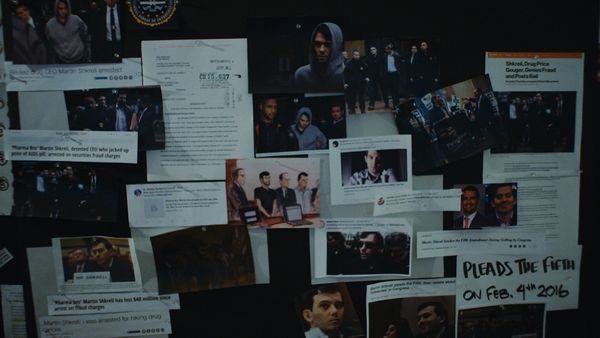

How does one tell the story of a man like Martin Shkreli? For years he spent almost all his time online, on camera, at work, playing computer games, eating his lunch, waffling on about whatever came into his head. That leaves very little for a documentarian to talk about. Brent Hodge tries and fails to tease out deeper aspects of character – it’s possible there aren’t any – but his film serves two purposes. Firstly, it documents neglected aspects of the Shkreli story for the record. Secondly, it explores something of the psychology of his remaining adherents.

In case you need a reminder, Shkreli was a business owner and stock trader with an interest in pharmaceuticals who attained infamy in 2015 when he hiked the price of a drug called daraprim – used to treat toxoplasmosis in immunosuppressed patients – to 56 times what it had been the day before. Hodge is wary of the sensationalism surrounding this, and looks for a new angle on the established narrative. He points out that price gouging is actually pretty common in the US market, making a case for regulation which few would disagree with. Whilst this is true, it comes across as the sort of “But everyone was doing it” defence that wouldn’t wash in primary school. Shkreli’s history of similar behaviour is barely touched on and he is given too easy a ride as regards his claim that no-one really got hurt, with a lot of conjecture and little real investigative vigour applied.

Perhaps this hesitant approach is due, in part, to the fact that Hodge is trying to get an interview with his subject, who doesn’t seem very interested. He is not a man who struggles to attract publicity, despite the fact that, as is acknowledged here, watching his broadcasts gets boring pretty quickly. Looking for people who might be willing to defend him, Hodge speaks to former girlfriends who seem dazzled by his fame. In one case there’s a hint of something deeper based around shared geekery, which is the closest the film gets to any genuine sense of intimacy with its subject.

Interviewing Milo Yiannopoulos, a man best known today for his increasingly elaborate comb-overs, Hodge extracts praise for Shkreli’s supposedly brilliant intellect. It’s unclear who this is expected to impress. There’s a trip to the village in Albania where the Shkreli name comes from, which reveals the kind of excitement one often encounters in small places when somebody vaguely connected to them makes it onto the telly. The only person who comes across as having real insight – and also the only person who seems to have changed his mind during the time he has known Shkreli – is the Wu Tang Clan’s Ghostface Killah. He’s clearly not in his element in this sort of interview, but he gets his point across and helps to give the film some depth.

The film extends over the period in which Shkreli purchased the Wu Tang Clan’s single-copy Once Upon A Time In Shaolin album and, later, the period leading up to his trial for securities fraud, ending with his conviction and sentencing. Here, no matter the opinion of them which you may have to begin with, it’s hard not to feel sympathy for a defence team whose client keeps mouthing off at every opportunity and saying the worst possible things. If one reflects on Shkreli’s trading history, one might conclude that he is a man of higher than average intellect whose escape from several sticky situations through sheer luck was mistakenly attributed to genius, leading him to believe that any effort to actually apply that intellect was unnecessary. Hodge, however, seems a little dazzled himself. In trying to get beyond what has already been said, he lends a lot of credence to poorly substantiated arguments. This in itself adds a level of interest to the film, albeit in a manner almost certainly unintended.

In the absence of much direct input from Shkreli, the film uses clips from his extensive past public engagement to make room for his own voice, which is more listenable in edited form. He is no less obnoxious like this, but that will doubtless please his admirers as much as it puts off other viewers, and it’s difficult to be sure how much of it is play for the cameras – he has demonstrated an awareness of the marketability of that persona, and it’s doubtful that this film would exist without it. The curious thing, however, is how ordinary he seems, and how little his fans seem to recognise that. Similar trolls are everywhere online, just without the marketing budget. The smirking, the misogyny, the superiority complex – it’s all very Nineties. And it’s this, in the end, that gives the film its real value – not because it presents a portrait of an exceptional figure but because it sums up a much broader behavioural phenomenon at a point where it seems to have run out of places to go. In decades to come, this will make for fascinating viewing. The big question is, how many people will really want to watch it now?

Reviewed on: 01 Oct 2021