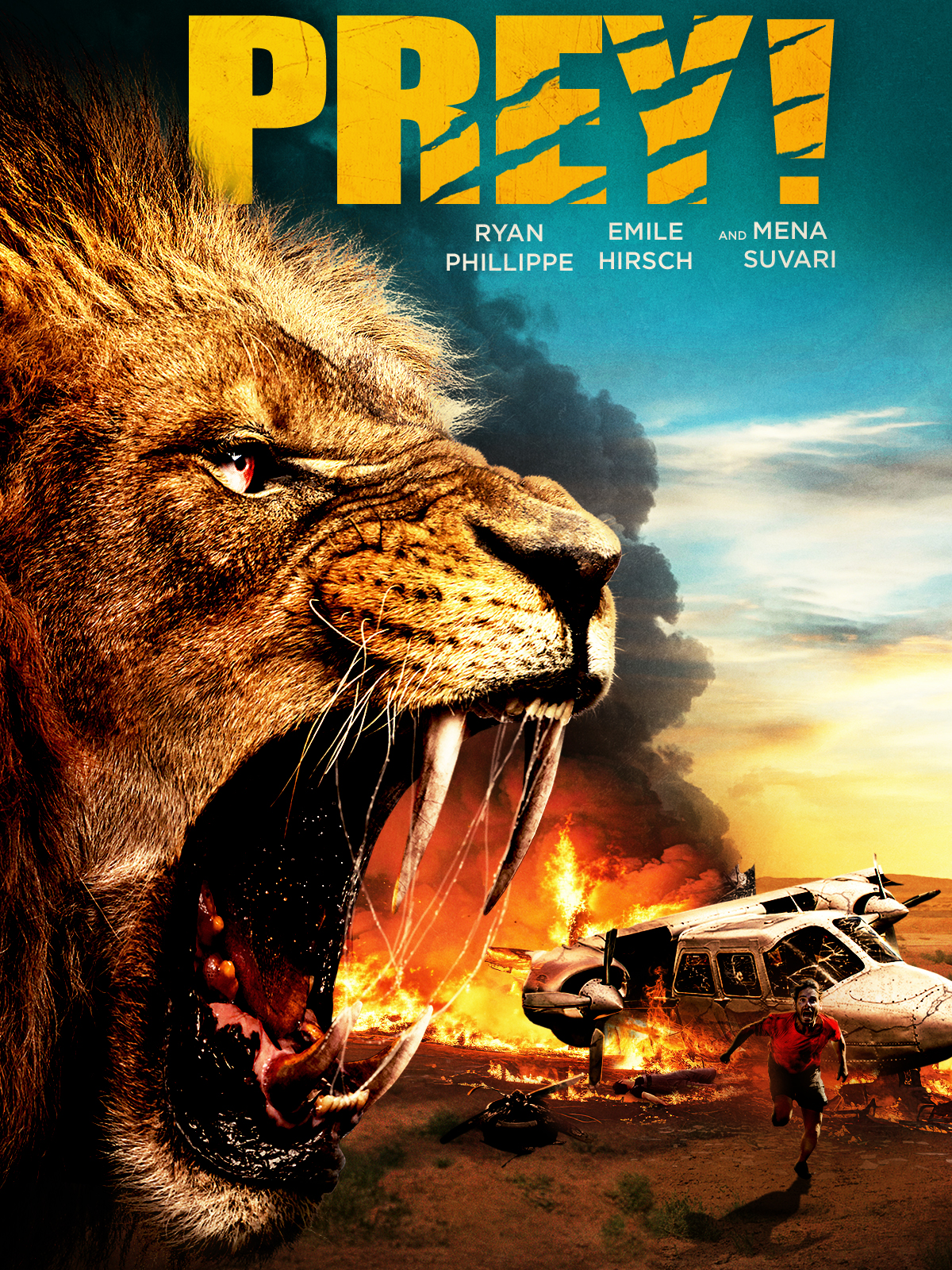

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Prey (2024) Film Review

Prey

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Like many male mammals, lions face a difficult path to adulthood. As they mature, it’s unsafe for them to stay with their families, because their fathers will start to see them as rivals. The practical alternative is for them to team up with other young males, often from different prides, to control the poor quality territories that the established prides are less interested in. This involves negotiating alliances even in the face of significant social differences, building trust and learning to work together. It’s the only way to survive, the only way to hold onto hope of one day living the good life with new families of their own.

Although some critics seem to have missed it, this is what’s happening with the lions in Mukunda Michael Dewil’s Prey. Three young males, inexperienced and desperate, are far more likely to mean trouble for humans than an established pride with much better culinary options. Perhaps Dewil has given his audience a bit too much credit by failing to provide an explanation of this. It’s ironic in light of the fact that he makes direct reference to how clueless Americans can be about lions. If you grow up on a diet of adventure myths in which brave white men with machetes can fight off any savage beast, you’re going to be totally unprepared for the reality.

Andrew (Ryan Phillippe) and his wife Sue (Mena Suvari) have visited Africa many times, but their experience is still quite limited. They’re Christian missionaries of the gentle, well-intentioned sort: he’s a doctor and she provides education to children, though it’s not clear whether or not she has any relevant qualifications. There’s a suggestion that this is filling a void for her, as they have been unable to have children. Working in the Kalahari desert, however, they can be vulnerable, and are savvy enough that when they learn they’re under threat from militants, they know it’s time to go. The only route out of there is on a light aircraft piloted by Grun (Emile Hirsch), who has no scruples about asking for 10,000 rand (about £4,000) each, with hand luggage only. Nevertheless, the plane is overweight, and when it goes down over a game reserve, they face other forms of danger.

This is, of course, the territory of the aforementioned lions – and like the lions, the survivors of the crash will have to work together if they want to survive. Their situation is complicated by the fact that Sue is injured in the wreckage, an unfortunate consequence of being the only one with a seatbelt. Scuzzy though he may be, Grun doesn’t want to leave her, knowing that predators will catch her scent. His plan is to hike out of there in the heat of the day, knowing that predators are more active when it’s cool, but getting everybody to cooperate is tough. Sue and Andrew believe that God will look after them no matter what they do. Thabo (Jeremy Tardy), the other African on board, shares his practical approach, but they also have to deal with two other outsiders, one of whom is gradually losing his mind due to grief and dehydration, the other of whom has no experience of hard work and thinks he can buy his way out of anything.

None of this particularly original, but it’s interesting to see the story approached from a more informed point of view, even if Dewil – who also wrote – has clearly missed the memo when it comes to the treatment of snake bites. Suvari does a lot with her character right at the start which helps not just to establish her but to give us a point of connection with the others. Phillippe has the most difficult task, with a character so overwhelmed that he becomes hard to relate to, and at times you might find yourself wishing that the lions would finish him off, but it’s interesting to see the actor take on something like this. Tardy is solid in support, injecting humanity and realism as needed, showing just the right level of carefully managed fear to persuade us that the danger is real even before things get bloody.

Hirsch, who is nothing if not prolific, hasn’t had great luck with his recent roles, but dominates most of this film and gets to remind us what he’s capable of. His character may be something of a cliché but he’s not unrealistic, and there’s a streak of emotional vulnerability undercutting his charisma even as he appropriates the role of leader. Importantly, he’s not as competent as he thinks he is, which allows the film to escape conventional macho pissing contests and do something more interesting.

There isn’t a big budget at work here and lions are not the kind of animals who can be tamed sufficiently for stunt work, so Dewil has to rely on suggestion, sound and bloody remains to let us know what’s happening. Inevitably, some viewers used to getting it all upfront will be disappointed by this, but others will find that the lions in their imagination are far scarier than anything cinema could present. The film is more effective in creating tension because deaths do not occur in the expected order, though an eyebrow or two might be raised when particular peril presents itself to a man wearing a red shirt. Dewil keeps open the possibility that he will kill all his characters, a trick which a handful of survival film directors have used before, and there is no point at which they are not massively disadvantaged.

It is perhaps not surprising that a survival tale which refuses to reward viewers for continuing to cling to colonial myths would attract some complaints, but if you’re prepared to engage with it on its own terms, Prey is an effective little thriller unafraid of acknowledging some uncomfortable truths.

Reviewed on: 28 Apr 2024