Eye For Film >> Movies >> Saltburn (2023) Film Review

Saltburn

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

Saltburn, we are told, is a place where one can lose oneself, but all of that is uncertain. Set mostly within the eponymous stately home, it is a gothic thriller dripping with signifiers. That it's technically a period piece, set in the distant past of 2006/7 might be enough to induce panic in some. Its unreliable geographies, human and physical, make it even more beguiling.

The screening Eye For Film saw had audio-description subtitles, an artefact of accessibility that some find distancing. In a movie full of things to be read it worked in its favour, if nothing else to satisfy the need to identify particular works in its dense soundtrack. We follow our protagonist, Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) over ancient cobbles to the courtyard of an Oxford College. Webbe (fictional), has a scarf, a blazer, a coat of arms. "Nice jacket," observes a passer-by, but we'll meet him again. The heraldry of Webbe contains a jagged line along its middle, in the argot of fields argent and that a 'dance'. We'll be led a merry one.

That observant by-passer is Farleigh Start (Archie Madekwe), also in Oliver's tutorial. I can scarce express how discomfiting some of these scenes are, the sense of uncommunicated institutional knowledge, of rules unexpressed but rigorously enforced. That's in part the personal, but scholars of any stripe should recognise the unwritten rules of class and classroom. Thus the reading list will matter as much as breakfast but if Oliver had seen Gosford Park he would not have made some of his mis-steps. Other works that might have helped him include some by Patricia Highsmith, but Mr Quick's talents are different than those of Mr Ripley.

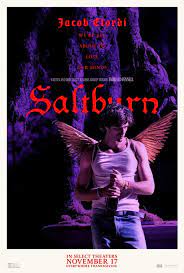

Later Oliver chooses not to pass by, a bicycling Samaritan to Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi). Felix is the scion of Saltburn, but all three will forge deeper connections there. Farleigh is family too, a poor relation of some remove. There is a complicated network of relationships, punctuated by Annabels and Indias and jealousies. Even the staff are part of them, the named and nameless footmen, the Butler Duncan (Paul Rhys), that tutor (Reece Shearsmith). As patriarch Sir James the mighty Richard E Grant, a different tyrant than in The Lesson but no less Shakespearean. A deliberate nod that, a party through a midsummer's night is a dream and a nightmare, shining as surely as the maze that the gardens overlook.

There's enough reference here that you'll be rewarded if you know your Puck from your Pet Shop Boys. King James and the Joker, and it's there that I think the film is weakest. Much like Todd Philips' film it embraces the possibilities of unreliable narration and an even less reliable protagonist before making certainties of things that were better as mysteries. There's strength in certainty, for sure, but there's art in obfuscation.

Emerald Fennel's second feature, one of the most striking things is that it's not an A24 film. Shot in 4:3 it looks incredible. Linus Sandgren has lensed excess before. Last year's Babylon was one of his, but nor is he a stranger to tuxedos and violence, having worked on No Time To Die the year before that. Reflections, candlelight, location shooting in real places, all are challenging for any production but Saltburn more than rises to it.

I'm not sure if it's the grounding in an era before widescreens were everywhere, the vagaries of the televisual as time travel. It could be the grain of truth, that it looks like I remember the world from that when when I was within it. There are moments where it appears a succession of album covers, a greatest hits of tableaux vivants. Shot largely at Drayton House, whose owner/occupant/inheritors the Stopford-Sackvilles are mentioned in passing, it means that one can look up sculptures in the grounds as part of the same sense of English Heritage as opening with Zadok The Priest. What might be Cain and Abel is possibly a later copy of Samson slaying a Philistine, and that piece's role as something either stolen or replicated or both, degraded or redefined by loss is itself indicative.

Monsters abound. Rosamund Pike as matriarch Elspeth has, as the trailer will tell you, an abhorrence for the ugly. Her wayward pal (almost always referred to, and credited, as) "Poor Dear Pamela" is Carey Mulligan. Among the many opportunities for semiotic analysis are the tattoos she carries and the way she carries herself. I found myself at various points thinking of the work of Iain Banks, though he was far from the only explorer of these landscapes. A novel of this type would probably have been the hit of that summer, bleaching beside the swollen pages of the Deathly Hallows. 'Salt-Burn' as a noun is attributed to DH Lawrence, and there's as much to censor here as there was in any of his works. There's more than the modern though, there's plenty of room(s) for the classics too. There's a minotaur in the centre of the labyrinth but black sails are spurned for red curtains.

I could (and am tempted to) go through the whole cast, Ewan Mitchell's (anti)social calculating is a striking contrast while Alison Oliver's Venetia blooms to new taboos. I owe an apology of sorts to Joshua McGuire as one of the multitudinous Henry. I had thought him Tom Hollander for a time. The interchangeability is, I'd submit, part of the point. There are moments of outright comedy, horror, a willingness to splash colour around as frenetically as any giallo.

It is not without flaw. The production is close to perfect, the house even has a book. There's not a note out of place on the soundtrack, but it's in the coda that I think it loses its nerve. Having baited hooks and reeled the audience in it too often and too far swaps its subterfuges for safety nets. Once it gets to Saltburn it only leaves twice, but those venturings are as fraught as Beowulf's from Heorot. Even Grendel had a mother. It's in the going back that the film shows its weaknesses, I felt it did not trust its grasp no matter how well it had disarmed its audience. I'm still eager to see it again, to revel in and with it, to be absorbed by its detail. A stately home not given over to the public, visits are more akin to treating with the faerie, bad bargains and all. Not a museum with a café, but an underworld. More ephemeral than a nectarine in Hades, less substantial than a cream tea, what passes for sustenance is largely perilous atmosphere. Behind the jam, it's gone.

Coda, on second viewing:

I said initially that I was still eager to see it again, to be absorbed by its detail. I am delighted to report that it rewarded another viewing. Some of that was the benefits of seeing a film with an audience with different expectations. The film has the glory of communal laughter. My showing had a set of young men experiencing what appeared to be a crisis of masculinity within their relationship group. Those were both elements of the film writ large. I had clocked a story about Shelley (the poet) the first time, but in seeing it again got the chance to see it again. A second go passes like a doppelganger at the window. Unlike vampires there's the opportunity to enjoy reflections. With forewarning there's more chance to see just how different Keoghan can look.

That said, on a reprise I feel even more keenly that the ending indicates a loss of nerve, one that does stick a little in the throat. That's a small weakness in something that's of great quality. I'm quibbling over the dessert wine after a feast, but it wasn't the tempest that gave us any port in a storm. For a second feature this has a confidence, an assuredness, and a voice that speaks strikingly to talent. Having watched it twice I not only look forward to seeing it again but to seeing what Emerald Fennell does next.

Reviewed on: 17 Nov 2023