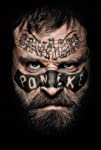

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Savage (2019) Film Review

Savage

Reviewed by: Mateusz Tarwacki

One can get the impression that in recent years gangster cinema has been experiencing a kind of renaissance, or at least an increase in the interest of creators. The bloody gangster pulp, familiar from the 1980s and 1990s (for example, Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction, from 1994, or Mike Newell's Donnie Brasco, from 1997) has been replaced cinema more reminiscent of the 1930s gangster pictures – portraits of a gangster as an ambiguous man, torn by doubts and the weight of his actions and, above all, sentiment. The turning point for this new outlook would be Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman from 2019, a kind of sentimental journey of settling accounts with the character model – a ruthless gangster. Sam Kelly is taking a similar path in his Savage.

The New Zealand director bases his sentimental journey on a broadly drawn socio- economic background and a portrait of New Zealand gangs over the course of 30 years – from the 1960s to the 1980s. We follow the changing street world from the perspective of Danny (played in adulthood by Jake Ryan an in early years by Olly Presling and James Matamua), a boy who starts his criminal path very early, indirectly turned on to it by domestic violence on a daily basis from his constantly drunk, violent father, who is unable to support his big family. When Danny is referred to borstal after an unsuccessful break-in, he will hear from his father a sentence that will form the basis of his life philosophy and identity: “You don’t ever bring shame on us!”.

Behind this strict code of a strong, brutal man will be the constant need for closeness and belonging to the group – an acceptance that Danny has not received from either his father or the equally violent borstal caretakers, feeding only on the illusion of closeness among his colleagues – an ambiguous relationship with Moses (also played by a trio of actors, John Tui, Lotima Pome'e and Haanz Fa'avae-Jackson) on which the ties of the future gang will be based comes on the fore. Savage is therefore a long and harrowing route to redemption – an unruly but sensitive boy does not die within the main character over these 30 years, but is trying to find his real family: biological, buddy or gangster.

Kelly not only plays touching notes by observing how the difficult coming-of-age boy becomes a gang enforcer, but also tries to outline the unique atmosphere of New Zealand's colourful street gangs, as well as seek answers to the question about the sources of violence. In this respect, the New Zealander's film is a picture that is better assimilated by the local viewer – because it uses the key of history and meanings more easily recognizable to someone who already knows the history of the last several dozen years in New Zealand.

Savage is a sentimental story on the level of evoking a historical contact – a portrait of street gangs – as well as the perspective of the hero's path, looking for his place on earth and redemption for his actions. Although as a genre cinema, Kelly's film fits into the current wave of new gangster cinema, one cannot help but feel that the creator wanted to put a little too much into his work. The picture of 30 years into Danny's life looks almost as chaotic as that of a real New Zealand street gang member – which in this case is not necessarily a compliment.

Reviewed on: 19 Jan 2021