Eye For Film >> Movies >> Slow Motion (1980) Film Review

Slow Motion

Reviewed by: Chris

I never did quite ‘get’ Dali. All those contortions. Grotesque shapes. Stunted creatures. Then one day I saw clues. His ‘melting pocket-watch’ (The Persistence Of Memory) was not just a silly timepiece, bent out of shape like wax melting off a table. It was the fluidity of time, how we perceive time in different ways. When we have fun (for instance) and time seems to speed up. When we’re bored, and it slows.

Our inner experience of time is affected by our perception. Our focus, our mental state, it makes a big difference. We are similarly affected by how things are presented externally. Trees flashing past so quickly they are almost a blur. Have you ever been on a train as it traverses a wooded hill? But see the same trees from the hilltop and their majesty and poetry become evident. In both cases, perhaps there is no absolute ‘reality’ – only different ways of perceiving it. At any one second, our senses are overloaded with more data than our consciousness allows. It is less a case of ‘seeing what is really there’ - but of exerting control over our selection process, our filtering, and deciding what data to take time to consciously process; and what our conscious mind ignores.

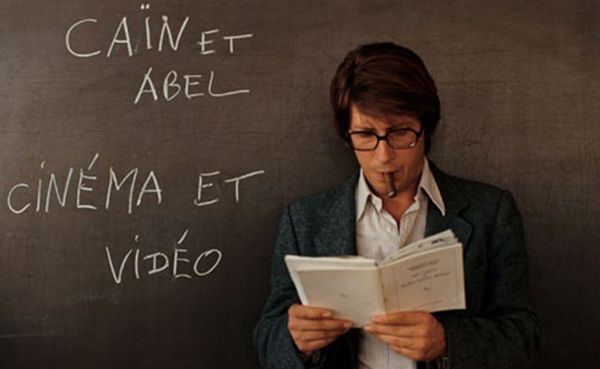

Perception is, for Godard, an enduring theme. Speed it up, slow it down. The camera mimics the process of visual perception. It chooses what to observe, and how. It ‘tells’ us what to think. Can cinema, by its careful control of simulated perception, increase our understanding of ‘how’ we perceive things? Or alert us to the possibility that there is ‘more’ in front of our eyes than we might have assumed on that busy day?

The nominal plot revolves around a three characters. A filmmaker called Godard. Denise, a writer/editor trying to make a career change. And Isabelle, a prostitute (Isabelle Huppert) trying to better herself. Godard and Denise are in the painful process of ending a relationship. He is also going through a tough time with his ex-wife and daughter. Denise sees Isabelle being abused in the street. Isabelle sleeps with Godard after going to a movie with him. She wants to get a new place to live – even phoning about a flat during a bizarre sex scene - and she wants to work for herself instead of the pimp. Not knowing Godard is the landlord, she visits their cottage up for rent as Godard throws himself across the table at Denise.

Three wildly different life trajectories. Intersecting in ways that allow the film to challenge accepted notions. Toying with the nature of perception. And even asking how we get to where we want to be in life – or not. Separate chapters - after the intro sequences - for each character. Then ‘Music’ brings all three together. (Look out for unusual sound tropes as well.)

Slow Motion – by whatever name we call it – is almost as conventional as Godard gets. While the narrative is far from mainstream, it is a more recognisable cinema experience than much of his most challenging (or didactic, uncommercial) work. And it provides material to sustain many repeated viewings. The only disclaimer – for anyone new to Godard – would be this: it is a film designed to make you think. Not to entertain. So if your criterion is the amount of emotion you will feel, please avoid. Godard has the artistic integrity, clearly demonstrated here, to make a movie to exalt and excite – but in the sense of exulting in intellectual enquiry – not by spoon-feeding us doses of dopamine.

The film includes about 15 ‘stop-action’ shots, where the image is stopped completely, slowed down, replayed, and/or speeded up. We don’t just analyse images outside of their diegetic function: we are able to invent a parallel diegesis. It is almost like the break-up of a relationship where a man and woman see ‘reality’ from totally different perspectives. Godard deconstructs his own maxim of ‘truth 24 times per second’ by varying the speeds. Outwardly hollow moments contain more than might otherwise meet the eye. It is not the subject matter and characters that demand Brechtian analysis, to become aware of our spectator involvement, so much as the process of perception itself.

In a scene where an executive orchestrates a scenario with two prostitutes and another man, we are again confronted with complex metaphor, (“Okay,” he says, “we’ve got the image, now we’ll take care of the sound.”) But here, the symbol of prostitution is not playing into the Marxist-bourgeois analogy so commonly used by Godard in films such as 2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her. In the debauchery, we can see the construction processes and their perception, the images, the sound, used to no specific purpose other than gratification – thus mimicking the production of mindless entertainment in Hollywood consumerist cinema.

Compounding such stop-motion tropes is the use of interior dialogue. Isabelle plays out another life in her head while having sex with clients. What do we choose to ‘see’? To hear? Comparison of the prostitution scenes and the scenes where natural, spontaneous sexuality is apparent or implied, coupled with the ‘selection’ process we make when determining how we ‘see’ things, might reflect not only on how men and women (or any two people) can be ‘in tune’ – but also, with different emphases affecting the data-perception process, the very gender difference apparent when we look at how men and women might typically view things differently. There might be life apart from the diegetic one. We might choose what we perceive to be ‘real’ – but ultimately we make our own reality.

The gender tension is kick-started by implied sexual imbalances in the film – mostly of men behaving badly towards women - or (as in the case of the hotel porter) an imbalance created by excessively obsessive desire and adulation. Even the brinkmanship of potentially erotic, disgusting or provocative themes is effectively subjugated to conscious analysis: any voyeuristic tendency in the viewer completely subverted. Rather than pandering to desire, controversial dialogues or scenes are made grotesque and anti-erotic.

Ultimately the narrative of Slow Motion is no narrative at all. Unlike more traditional stories encountered in Pierrot Le Fou or A Bout de Soufflé, with Slow Motion, the ‘narrative’ is simply a series of characters and events on which to hang material for various readings, and it is these readings that provide enjoyment, our questioning of what we see. It is easy to be more interested in what we think about (for instance) the feminist implications than how they apply to specific characters in the film. One ‘reality’ is suggested (such as Godard the film director being represented in his own movie) only to have that reality snatched away (it’s just a character with similar interests and surname). This ‘cleverness’ – and another example might be a ‘window’ that turns out to be a mirror – is not there merely to impress us with ingenious symbols: its effect is to deconstruct the ‘reality’ we repeatedly buy into, so that we question the nature of perception rather than the fictional plot.

Denise, in her interior monologue, speaks of, “that thing in everyone which silently screams out: I am not a machine.” If a machine (the camera) can imitate perception, how is a human different to a machine? Denise longs to be (or become more like) the director or cameraman or woman, the person ‘behind’ her mechanical actions. One character has moved from the countryside to the city. Another longs to move to the country. A third seems to drift perpetually in hotels.

Dehumanization occurs when a person is not able to order their life according to their will. At that point, the individual has become a slave to the senses rather than their master. One might not be able to change the territory in which one finds oneself – but, by standing back far enough to discern the wood from the trees, one might at least find new perceptions that can be converted to reality.

Reviewed on: 22 Jun 2011