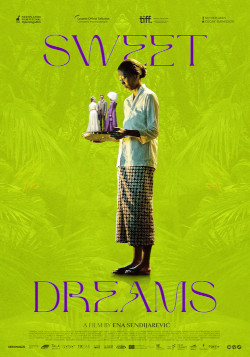

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Sweet Dreams (2023) Film Review

Sweet Dreams

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There’s an idleness about the opening of Ena Sendijarević’s latest work which, in itself, speaks to the experience of Dutch colonials in Indonesia. Beguiled by the beauty of the jungle, its trees so tightly enmeshed that they almost conceal the river flowing through it, we are drawn into a landscape where the hum of mosquitos is omnipresent, where nothing can escape the suffocating heat. There a group of local men are setting up a trap, dangling a piece of meat from a tree, luring in a tiger for a pampered boy in linens and pith helmet to shoot.

The boy is Karel (Rio Kaj Den Haas), the brown-skinned son of sugar plantation owner Jan (Hans Dagelet), who proudly carries him home upon his shoulders as his servants struggle with the weight of the slain beast. Jan adores the boy, moulds him in his image, invites him to laugh along as he ridicules a fallen servant by ordering him to jump up and down. The boy’s mother watches from a distance. She is Sítí (Hayati Azis) a complicated woman who looks after the house, dances for Jan, trades access to her body for a slightly more comfortable life but won’t any man take ownership of her. She is caught in a complicated relationship with colonialism which is about to become more complicated still.

The death of Jan does not, in itself, seem like a big event. His widow Agathe (Renée Soutendijk, whose performance won her an award at Locarno) is singularly unmoved. Her focus is on selling the house and finally getting back to civilisation. To that end, she summons her son, the primly moustachioed Cornelius (Florian Myjer) and his swooning, pregnant, gingham-clad wife Josafien (Lisa Zweerman). Plans are quickly put in place, but everything crumbles upon the discovery that Jan left his entire estate to Karel.

He must have been mad, they suggest – but madness is everywhere here. In one scene, a group of locals struggle to perform a string concerto for the local whites, who dance and drink around the corpse of the tiger in a room whose deep red walls are blotchy with damp. Agathe is overdressed as always, with tight lacing and a high collar, layered brocade, exuding a chilly quality which seems to shield her from the heat. Another woman of a similar age enthuses at her about the delights of the telephone, but she is suspicious of such new-fangled nonsense; it cannot ease her loneliness. In a bright green room she writes letters. In the refinery where the sugar is processed she takes desperate measures.

Josafien, too, is suffering from the heat. Ripping open her own bodice to ease her discomfort, she catches the eye of local working class hero Reza (Muhammad Khan), who is also pursuing Sítí. Of the three, Josafien is the most willing to compromise, gradually allowing this new environment to change her, to bring out a wild side – yet she knows that to give birth there, with so little support, could be the death of her. As other characters drift around, scheming and failing to deliver on their various schemes, she is running out of time, growing frantic in the languor of the tropics. Sendijarević saves most of it for the final act, when she introduces moments of surrealism to aid her in exploring Sítí’s psychological trap, and through it the subtler sociological effects of colonialism.

Sítí does feel something for Reza, perhaps because of the allure of his dynamic simplicity, but she understands the compromises and complicity of the social arrangement on a deeper level, fearing for her son and for others who must live with what he is becoming: a creature of two worlds, with all the fury of the colonised and all the entitlement of a young aristocrat. The matter of the estate is concluded in a predictable, albeit poetic way, but the boy never quite fits into the fairytale Gothic of the story. His is the hard-eyed look of modernity.

More poem than conventional narrative, Sweet Dreams explores the tropes of the colonial fable with a romantic eye and a sharp wit. There is a little sympathy present even for its most monstrous characters, but very little mercy for anyone. Its lack of heroes or solutions reflects the failings of the colonial project itself, but it does not invest much hope in what comes next. When we finally sink into the darkness of the jungle again, on a sweltering night, it is clear that there will be no easy dawn.

Reviewed on: 12 Apr 2024