Eye For Film >> Movies >> Take Care Of Maya (2023) Film Review

Take Care Of Maya

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

If you spend much time around people with disabilities and chronic illnesses, you will hear a lot of horror stories about damaging decisions made by doctors who are fundamentally unable to imagine how different other people’s experiences can be from their own. How much more terrifying that must be when it is not one’s own life and liberty on the line, but that of one’s child. If you have personally struggled with issues of this kind, you’ll find Take Care Of Maya hard to watch, but it is an important watch. For people working in healthcare or child support, it should probably be mandatory.

A Netflix production which premièred at Tribeca 2023, the film tells the story of the Kowalski family, who lived an unassuming life in Venice, Florida, until, in June 2015, nine-year-old Maya began to fall ill. She had suffered from a commonplace respiratory infection but went on to develop lesions, experience chronic pain and fatigue, and became unable to walk due to dystonia, with her legs turning inwards. As her condition got progressively worse, her worried parents, jack and Beata, took her to an assortment of doctors without any positive results. Some didn’t even believe that Maya’s symptoms were real.

Relief came when Dr Anthony Kirkpatrick, who is interviewed extensively here, diagnosed CRPS (complex regional pain syndrome), and prescribed a five day ketamine coma procedure. This risky treatment, for which the family had to travel to Mexico, actually got results, at least in the short term. Eventually Maya relapsed and her parents rushed her to Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital as an emergency, but that’s where fate took another unfortunate turn. When staff at the hospital realised how much ketamine was on, they not only withdrew her treatment, but revoked her parents’ custody, diagnosing Beata with Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy and accusing her of child abuse.

Were they right to do so? The film positions itself very strongly on the parents’ side but does allow other voices to be heard. Giving anybody that much ketamine is certainly dangerous and one can understand why it inspired concern, though the parents felt that they had been responsible by following a doctor’s instructions, and Kirkpatrick argues that Maya would have died without it. Additional psychiatric evidence is supplied to challenge the claim that Beata was mentally ill, and some of the comments subsequently made about her by doctors at the hospital fit depressingly neatly into a centuries-old pattern of writing off ‘difficult’ women.

Perhaps most worryingly, a journalist’s investigation of the case revealed numerous similar incidents all linked to the same hospital and one particular paediatric abuse specialist. From a statistical perspective, it looks as if something is wrong. That specialist does get the opportunity to defend herself but doesn’t bring up any evidence beyond what we’ve already seen – at least not in what is presented here.

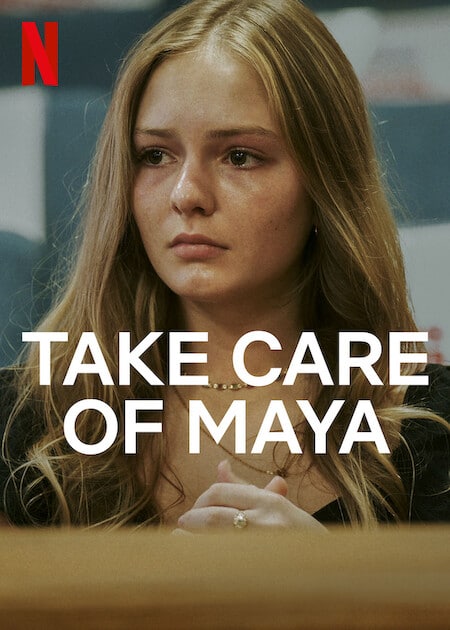

In many ways the film has the character of a TV special, piling on sentiment when it really doesn’t need to in order to get its point across. In places its polemical approach makes it hard to take seriously, but despite this, it makes a pretty convincing case. The family’s story contains multiple layers of tragedy and with this in mind one might also be concerned about exploitation. The fact that we only occasionally see Maya’s younger sibling provides some reassurance on this front, suggesting that a wish to retain some privacy has been respected. Maya herself is now in her teens and comes across as a sensible young woman capable of making her own decisions in that regard.

The film raises concerns not only about the specifics of this case and those with factors in common, but also about the apparent lack of a functional appeals process, and bias towards assuming the original decision was correct which prevents some professionals from rationally evaluating the facts. There is an acknowledgement from Maya’s father that child protection officials have to be able to do their job, though the film perhaps leans a little too heavily into the assumption that abusers are easy to recognise and never come across as nice people with whom it’s easy to sympathise.

Heavy handed though it is, this film will doubtless have real value to people in similar situations, who can be made all the more vulnerable by isolation. It has important points to make about the devaluing of women’s, children’s and disabled people’s voices, and about the dangers of unchecked power, even where that power is used with the noblest intentions.

Reviewed on: 11 Jun 2023