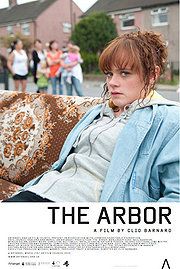

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Arbor (2010) Film Review

The Arbor

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

It is almost impossible to discuss artist/filmmaker Clio Barnard's remarkable documentary without going into at least a little biographical detail concerning its subject. Andrea Dunbar is not exactly a household name. In the catalogue of playwrights/screenwriters she has a very modest entry, not least because she died when she was just 29 years of age. Yet, many aspects of her story - and her legacy - are universal, particularly for those who struggled to find a way out of many of the 'sink' estates and 'schemes' of Britain in the Eighties and Nineties.

Bradford's Brafferton Arbor - from which Andrea's play of the same name and this documentary take their names - is typical of a northern English urban housing estate of the period. Alcohol is a regular feature, drugs not uncommon and a 'free-range' mentality towards sex and children far from unusual.

Despite this, at just 15 years old, Dunbar wrote her first play The Arbor. Miraculously, considering her under-privileged background, it found its way into the hands of Max Stafford-Clark, at the Royal Court Theatre, who was so impressed with the warts-and-all largely-autobiographical story of a woman's love affair with her Pakistani boyfriend on a racist northern estate, that he staged it. She went on to write, the also largely autobiographical, Rita, Sue And Bob Too! although she later came to loathe the filmed version of the life and loves of a man and his teen babysitters after the ending received an upbeat makeover.

Ten years after Dunbar died, Stafford-Clarke returned to Brafferton Arbor to see what changes had happened in the community and to write a new play A State Affair, based on testimony from those who lived there. What he found was that virtually nothing had changed for the residents, except that drink had picked up a bedfellow of drugs as the escape of choice - and that Andrea's legacy, particularly for her eldest, mixed-raced daughter Lorraine, was nothing but heartbreak.

It is this revisiting which prompted Barnard to become interested in what happened to Dunbar's children - and helps to explain why this documentary stands on its own as a radical piece of work that is certain to garner a slew of awards. Instead of merely considering Dunbar's life and work, Barnard wants to crawl beneath the skin of the society in which she lived and to look at the circumstances which led to her writing, Dunbar's legacy is scrutinised, but so is the legacy of the estate itself.

The main device she uses is almost a mirror image of that employed by Dunbar. As Dunbar used the facts of her life to create her 'fiction', Barnard uses tropes we usually associate with fiction in order to present the facts. Chief among these techniques is the use of actors to portray everyone in the film. But although they are in one respect 'fictional' representations, the words they are mouthing are the real, lip-synched voices of the people in Dunbar's life. It is surely no mistake either that Dunbar's sister Pamela is played by Kathryn Pogson, whose connection to Dunbar stretches back to The Arbor's original production, when she played "The Girl" or that George Costigan (Bob in Rita, Sue And Bob Too!) takes on the role of one of Dunbar's partners, Jimmy "the Wig". This constant mix of fiction and fact has multiple benefits. It makes you ever-aware of the nature of Dunbar's work as a hybrid animal, shows that even documentary can be slippery when it comes to representing the 'truth', affords those relating some, often very disturbing, memories a high degree of privacy and allows Barnard masses of artistic freedom when it comes to recreating scenes from the children's past.

She puts this freedom to good effect right from the outset, when she is able to 'reimagine' scenes of the children accidentally setting their bedroom alight in a bid to keep warm. In doing so, she evokes the atmosphere and ghosts of the past, while the real-life testimony of those she interviewed keeps you firmly anchored in the present. Use of some fascinating television archive footage of Dunbar herself, meanwhile, gives the playwright a presence in which she can, at least partially, speak for herself. The end result sees memory, reality, fact and fiction blend to give you a vivid 'feel' for the interviewees' recollections while being acutely aware that this remains a remembered reconstruction of the past.

Barnard doesn't stop there. She also takes the idea of Andrea's work and life being intrinsically linked one step further by getting actors to stage scenes from The Arbor in the street, while the community look on. Like everything in Barnard's film, this serves more than one purpose. Unknown Natalie Gavin, who plays The Girl, is both a superb actress and something of a ringer for Dunbar. So by weaving these scenes in between the testimony of Dunbar's family - including her second daughter Lisa Thompson and son Andrew (whose Caucasian ethnicity means they had an entirely different experience at the hands of both their mother and the local residents than the less lucky Lorraine) - Barnard is able to show just how much of the play was drawn from the playwright's life. And by staging them in the street as she does, she also adds another layer to our understanding of the make-up of the community - since they form an audience as the scenes unfold.

The end result is not so much a celebration of a life as a dissection of a legacy - both on a personal level and from a much wider society perspective, where even prison can seem like a welcome escape. This is a fiercely intellectual piece of cinema that still manages to grab your heart and punch you in the gut.

Reviewed on: 16 May 2010