Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Arc Of Oblivion (2022) Film Review

The Arc Of Oblivion

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

If there’s one thing we know about the universe, it’s that nothing lasts. The Earth is four and a half billion years old – it has about two billion years left to go. Given enough time, all the stars will burn out. Even the constituent parts of atoms will eventually be ripped apart. In light of that, why do we humans strive so hard to leave our marks upon the world before we leave it?

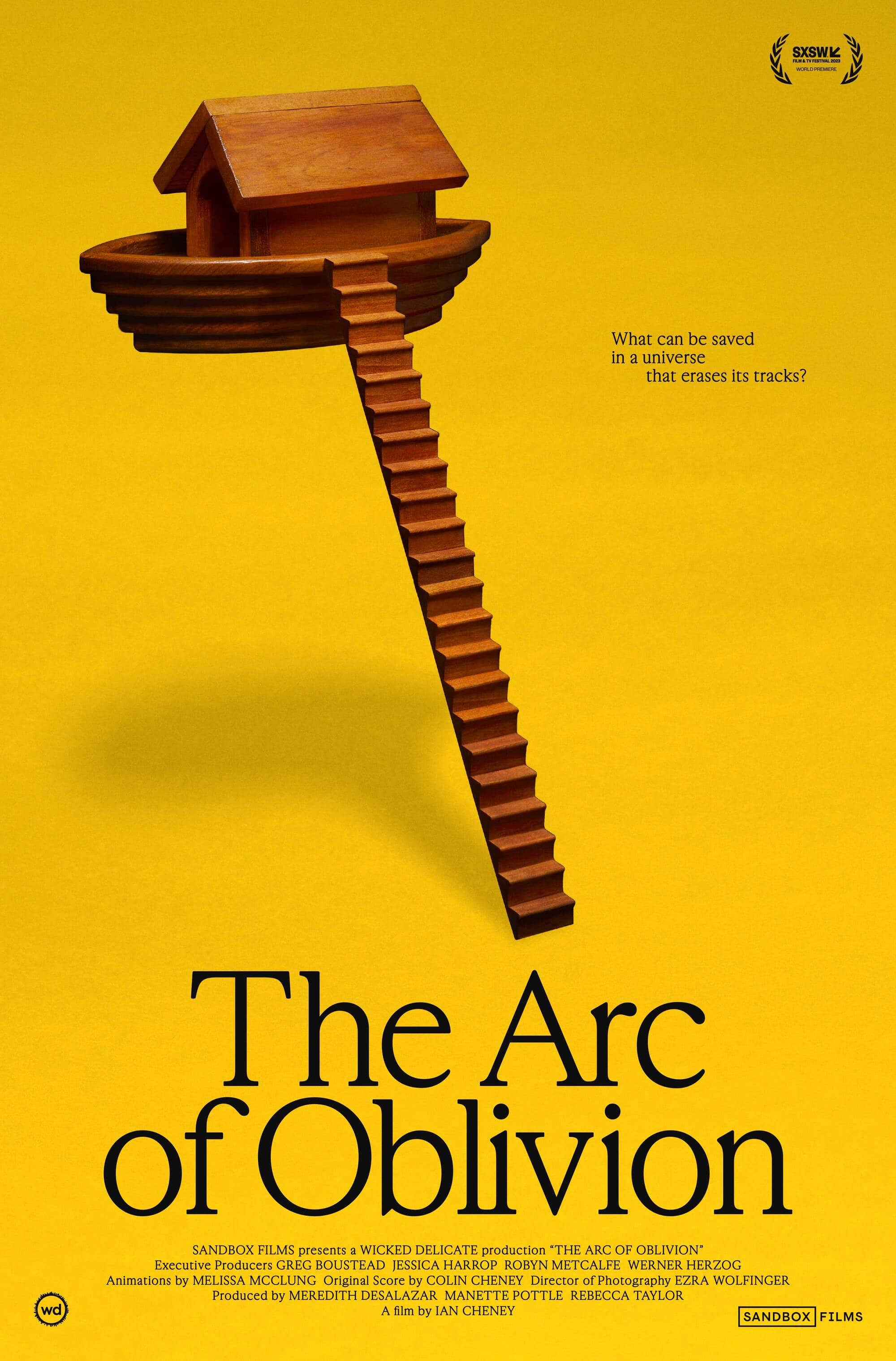

Ian Cheney is building an ark. “I don’t really know why I'm building it,” he says – which is, one imagines, what it might feel like to respond to a divine command. He’s building it in the field behind his parent’s house, using wood cut from the trees which grow there. A neighbour who is actually a competent carpenter is doing most of the work but Cheney is engaged in the important task of keeping an ark journal. He’s fascinated by the stories behind this phenomenon – not just in the Bible, but before that, in the Epic Of Gilgamesh. Along the way, however, he discovers other stories, other forms of record keeping, starting with the rings in the trees.

To archaeologists and palaeontologists, and even historians, it’s not just the deliberate marks which matter. Following threads which connect to one another and to the people from whom he borrows expertise, Cheney moves from trees to fish ear bones, which also lay down rings year by year. Travelling, he finds the fossilised footprints of ancient goats and reflects on the tiny shells in limestone cement which evidence the lives of molluscs even older. This awareness of deep time is important to giving the film weight, but there is also a look at the more recent term and, in the film’s most poignant stretch, at what it means to be denied a record.

The experience of enslaved African Americans, whose details were recorded for the sake of commerce but who rarely got the chance to set down their own stories, is told by a historian working to uncover the secrets of graveyards which have often been subject to intentional destruction – if there is perceived value in leaving a mark, then there would seem to be something similar in taking it from others. We also hear from a woman who lost all her family records and treasured possessions to a hurricane, who raises something which often helped people in the former circumstance: the significance of the oral tradition as a means of preserving important information, passing stories along in a manner sometimes more resistant to calamities.

Why don’t we record everybody’s story? Cheney wonders. We could, today. it might not last forever but, as the graveyard researcher says, people deserve their time. This leads to an exploration of modern storage options. Some scrolls and books have survived for thousands of years but, proportionally, not very many. Digital information, on our current recording formats, is vastly more transient. We meet a ceramicist who bakes people’s words and images into tiles and stores them in a vault inside a mountain, one of the best time-tested methods of preservation. Archaeologists of the future may well discover these intact, but of course, one can’t really communicate very much with them. A much better method of storage – and one which has been around vastly longer than we have – is DNA. We can code information into it, but at present, it’s very expensive to do so. Might that change?

“We’re all asking...what in this world is worth saving? But I’m starting to wonder if that’s the wrong question,” says Cheney. He sounds portentous, but never quite seems to figure out what the right question might be. For all the fascinating material assembled here, the film feels a little flimsy, less than the sum of its parts. Odd little things are included, like a complaint about not being able to film in the Svalbard seed bank, which is curious (as other filmmakers have done) but goes unexplained. The film contains powerful moments but Cheney doesn’t quite seem to know how to draw them all together.

There is a clear aspiration here to create something like the directorial work of one of the film’s producers, Werner Herzog. His brief rumination on the experience of growing up in the shadow of war, amongst people who had lost everything, embodies the kind of wisdom which Cheney will need more time and patience to acquire. Right at the end, at Cheney’s request, Herzog sits in the completed ark reading Ozymandias. If not quite amongst those moments which one might prioritise for safekeeping against a coming flood, it is, at any rate, a pleasure in the moment.

Reviewed on: 31 Mar 2023