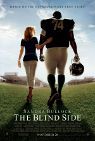

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Blind Side (2009) Film Review

If you were in the audience for Erin Brockovich and shouted out: "What’s all this lawyerly bullcrap, where’s my goddamn football?" then John Lee Hancock’s The Blind Side was made for you and you only.

Early on in the movie we find out that the husband of the main character, played in shameless-saint-mode by Sandra Bullock, is the owner of 70 fast food restaurants, including Taco Bell. It recalls the words of Bill Hicks, that famously acerbic comedian, who asks the point of a menu when all you’re being asked is how you would like your beans and flour arranged. Squelch. It’s simple, sloppy and unappetising. No variety, no soul, no substance unless it’s manufactured, over-processed and fake.

It’s the film in a nutshell and if it didn’t sledgehammer every other point it was trying to make you’d think it was even poking fun at itself. But no, this is as safe and sterile as filmmaking gets. Unless of course you’re willing to prod beneath the surface.

Apparently based on a true story, the film revolves around the relationship between Leigh Ann Tuohy (Sandra Bullock) a wealthy Memphis socialite, doting mum and woman of faith, and the simple-minded giant Michael Oher (Quinton Aaron), who she takes under her wing. Coming from a poor, black neighbourhood, it’s thanks to his sporting abilities that Michael finds a place at a local Christian school, a room in Leigh Ann’s home and eventually a place in all our hearts.

Of course, our hearts are tiny in comparison to Michael's. Dwarfing even the titanic form that makes him a perfect fit for the position of left tackle on the school’s football team, he’s as good-natured and harmless as Ferdinand the Bull, that oh-so-cherished character from childhood. We know this because both the film, and Leigh Ann make repeated reference to it, like the audience were exactly as Mr Hicks described: bovine America. Dull-witted ideocracy. The football team that suffered too many knocks, sending it into a permanent stupor.

This is a single symptom of a deeper sickness. Scene after scene goes by, the director and actors, caring less about creating something fresh than signposting the most obvious conflicts. Well, of course, the player that gives Michael so much trouble at his first game has to be the son of the biggest, most vocal redneck in the crowd. Is it really surprising that Leigh Ann admonishes her friends, all of them little more than clucking, ignorant hens, revealing their hypocrisy in caring more for status than they do real Christian values?

A traffic accident is the worst of the bunch and brings up the unpleasant heart of the movie. Shortly after we are told that one of the few things Michael scored highly in was protective instinct, he blocks the air bag that would have crushed Leigh Ann’s son (arguably the most obnoxiously cloying, cutesy and precocious moppet ever depicted on screen). A horribly manipulative moment aside, it’s the fact this instinct is then pounced upon as the one trait that makes Michael perfect for the football field that’s so abhorrent.

Everything leading up to this moment has been a relatively harmless collection of insipid clichés, as Michael is embraced by the moral force that is the Tuohy family. Now it’s all about the football and while it’s a sport I can appreciate on the field, it’s everything off the field that’s both more intriguing and equally insidious.

And yet, unlike the films that expose how entire schools can be dominated by the sport both financially and spiritually. How children can be driven down by the pressure from both their peers, parents and their teachers. How a single injury could seemingly be the difference between a life of success and a life of abject misery. We see none of it in this film.

It’s the friendly face on something tantamount to facism. Michael is turned from this big, black Buddha floating on a sea of redneck Bubbas into a tackling terminator in a video made by a child. His aggressive tendencies, the ones that nearly result in him hurting a baby, are advocated as long as it’s on the football field and for the right college. Where no barrier stands in the way of a poor, black kid with the white, and right backing and a clunky sporting metaphor or two.

Any moral dilemma is brushed aside by a reaffirmation of Leigh Ann’s good character as she sashays through the film, patting bottoms and shaking hands, her jewellery clinking, her heart firmly on the sleeve with the designer label on it. It’s a character that should be beneath Bullock, her wit and natural charm in too great a supply to stoop to such Oscar-baiting trash.

Reviewed on: 26 Mar 2010