Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Bloodstained Butterfly (1971) Film Review

When a young woman is murdered in a park following a thwarted sexual assault, the hunt is on for the killer. So far, so giallo. But after her friend's father is arrested and taken to trial, the killings continue. Was he innocent after all? How are the deaths connected? Can the killer be stopped? These questions move to the fore, squeezing out the glamour and gore more commonly associated with genre. The focus is on the mystery which, though ultimately simpler than many, unfolds in a way that will keep you guessing all the way through.

With its focus on police procedural work and courtroom drama, The Bloodstained Butterfly foreshadows several of the the crime series popular on TV today. It won't satisfy all giallo fans because it doesn't really deliver on the horror and doesn't have the same overwhelming visual impact as the genre's best loved works, but its intelligent approach extends to the visuals. Director Duccio Tessari delivers a beautiful opening scene, shooting from multiple angles to capture the complexity of a day out in the park for two girls whose raincoats shimmer in anticipation of Don't Look Now. The final sequence takes a similar approach as it compares two characters, and uses intercut scenes which illustrate that Tessari (in partnership with cinematographer Carlo Carlini) is more than capable of producing the vivid, conventionally beautiful scenes common to the genre, which highlights the fact that the drabness of much of the film is a conscious choice. Through that drabness, the colour yellow guides us on our journey, from the raincoats to lines painted on the road, a dead woman's skirt, a pair of trousers: literal giallo.

Equally important to Tessari's style, and at the heart of what makes this an important transitional film (though it came out in a year rich in more conventional giallo works) is the use of the modern. Sadly, this has led to it dating more than many of its contemporaries, as it doesn't share their sense of timelessness, yet the film has a self awareness that compensates for this. The biggest problem is with the adoring shots of cars, doubtless stylish in their time, which now look cute and boxy if not outright ridiculous. There's also some pretty ugly modern furniture, but it's less intrusive and it neatly contextualises the various characters' endeavours. Traditional baroque furniture only appears in profusion in one location, where it is associated both with artistry and with brutality. Gianni Ferrio's music, meanwhile, is pure giallo and elegantly links these different worlds together.

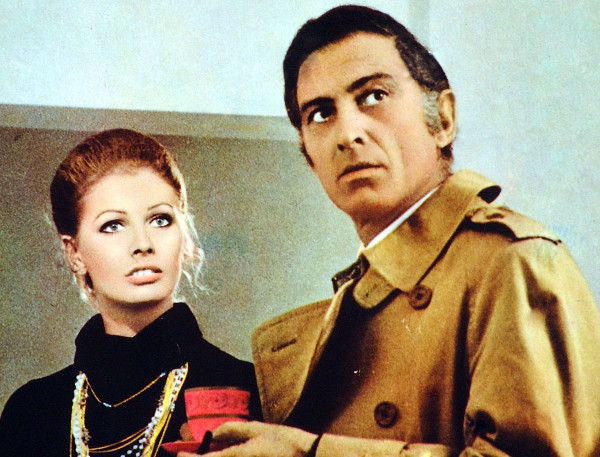

In structure, this film owes much to the crime fiction of the time, opening with an introduction to each character and carefully arranging its revelations like a series of end-of-chapter intellectual cliffhangers. The translation between forms is not entirely successful. In places it's too slow and the acting doesn't grip as much as it needs to, though even in the English dubbed version it's distinctly less schlocky than genre fans might expect. A love triangle at the centre carries most of the emotional weight but doesn't always ring true, whilst a sex scene between two other characters, intended to be intense and aggressive, instead gives the impression that neither actually wants it. Carole André, however, lights up the film in her brief appearances as the first murder victim (and the only one we really get to care about).

In keeping with its modernist tone, the film delivers interesting asides on social issues of the time, from homosexuality to sex work, creating an awareness that there's a wider world in which this drama is being played out and that that world, too, is going through a period of upheaval. Though Tessari's film is not entirely successful it is innovative, ambitious and a must see for anyone interested in the history of the genre.

Reviewed on: 18 Aug 2016