Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Brood (1979) Film Review

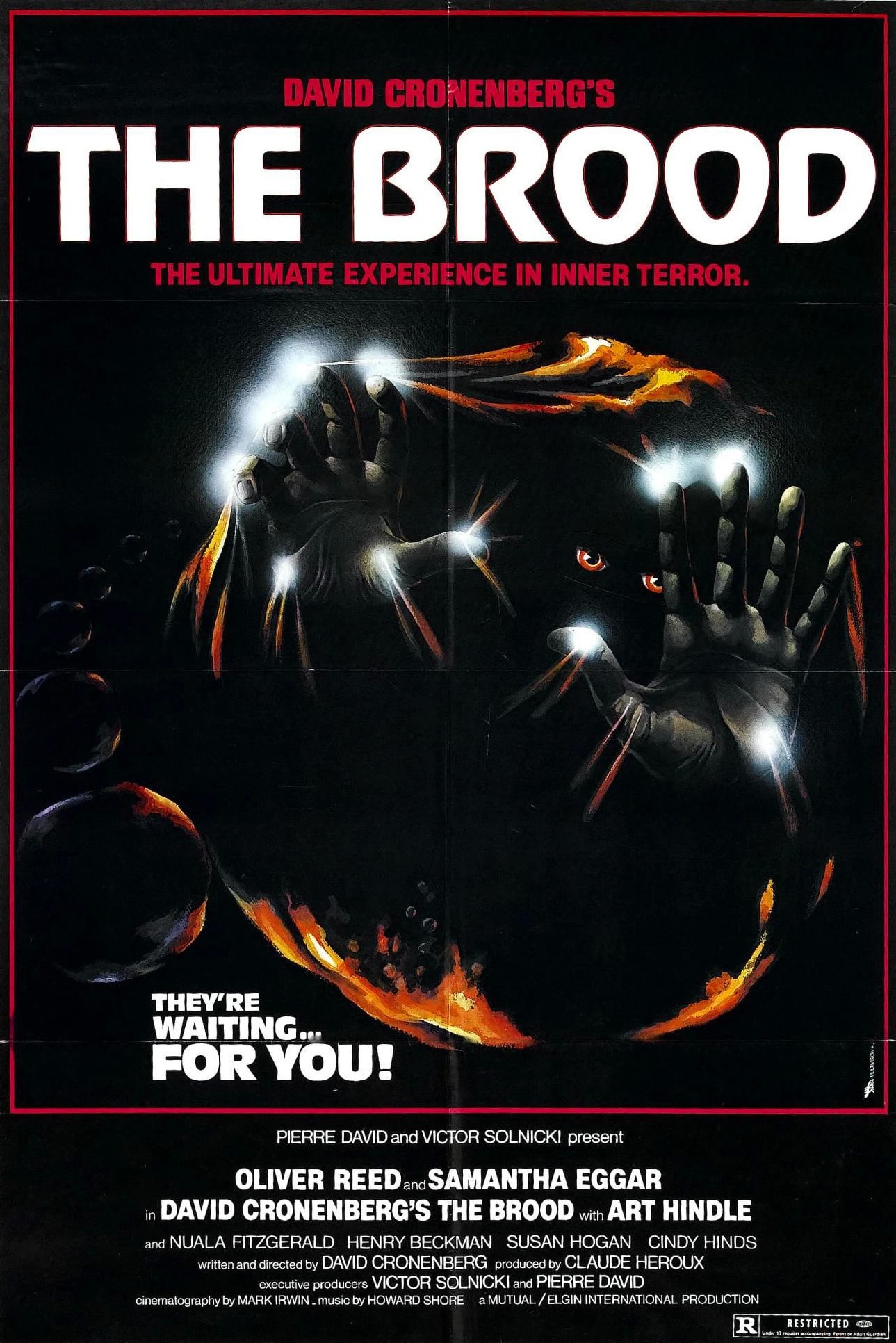

The Brood

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The theory that what is inside the mind can become manifest on the body has been kicked around in various forms since ancient times and its influence is still felt today, sometimes with serious consequences, as when politicians persuade themselves that disabilities can be willed away. In the Sixties and Seventies it was particularly prominent amongst self-help gurus, and David Cronenberg’s messy but influential horror film exposes and exploits this, taking it to an extreme. Though not entirely successful as a piece of entertainment, it represents an important stage in the development of body horror cinema. It’s also of interest to students of the director’s work, as its satire has a very personal aspect related to the breakdown of his first marriage and the custody battle which then ensued.

In the film, we see Cronenberg’s alter-ego Frank (Art Hindle) trying to keep his five-year-old daughter Candice (Cindy Hinds) from spending court-appointed time with her mother Nola (Samantha Eggar), whom he suspects of abusing her. Complicating his efforts is the fact that he can’t discuss the matter directly with Nola because she is resident in a private psychiatric clinic, undergoing intensive therapy. Her psychiatrist, Dr Raglan (Oliver Reed), believes that it would harm her progress for her to see her former husband.

As Frank engages lawyers and tries to find a solution, events take an unexpected turn. As if conjuring up the spirit of Nic Roeg’s Don’t Look Now from six years earlier, a small figure in a bright red, hooded coat begins murdering people close to Frank. In due course it will emerge that this figure, and others like it, are connected to Nola’s experiences at the clinic, ultimately leading Frank to a discovery which horrifies him and forces him to take drastic action if he is to save his child.

Reed has the perfect combination of gravitas and ham to play Raglan, a man whose reckless treatment of his patients seems rooted in the classic egotism of the visionary ‘mad’ scientist rather than in any explicitly malicious urge. There is a great turn from Gary McKeehan in a bit part as a vulnerable patient hurt by his neglect as he becomes increasingly obsessed by Nola. Eggar, who had worked with Reed before and had a natural chemistry with him, throws everything into her role, giving her the weight of a figure from Greek myth, embodying the monstrous feminine and yet still retaining some sympathy. Like Echidna, Nola is scarred by tragedy, punished for acting according to her nature. She never enjoys true agency, manipulated by the male characters, yet retains the potential for it, struggling to express herself in the only way she can.

Although some critics have perceived the film as misogynistic, that’s very much up for debate. It certainly can’t have made easy viewing for the director’s ex-wife (though many people, regardless of gender, doubtless indulge privately in more extreme fantasies when going through the tumult of divorce), but Nola is too complex a character to be limited to this. Furthermore, her particular manifestation of feminine potential, through its externality, becomes almost separate from her materiality as a woman. When one relates it to Cronenberg’s later body horror works like Videodrome and eXistenZ, it’s apparent that this could happen to anyone. Frank isn’t threatened merely by the existence of the feminine (even in light of the film’s final scene); there is a suggestion that he could become the feminine.

In reading the film like this, one must exercise caution: for all its intellectual dimensions, it is simultaneously a very silly tale with unconvincing monsters, reliant on cheesy horror tropes. The effects work stands up pretty well, but Hinds might as well have been carved out of wood, and as a result it lacks a redemptive emotional core – Hindle tries but has no chemistry with the child. It has also lost some of its power simply due to the passing of time and changing social attitudes. Societal familiarity with ostensibly more extreme cults makes Raglan’s clinic seem less sinister than it did. Some moments play very differently from the way they originally did, such as when Nola’s father, having confronted Raglan, prepares to drive away down an icy road. “Should I have him stopped?” asks a minion. “No,” says the doctor. “He’s drunk.”

Though it’s far from the director’s best work, The Brood is quite watchable and has spawned a host of imitations. It provides important context for his later films. If you really want to appreciate Crimes Of The Future, you need to reckon with those of the past.

Reviewed on: 14 May 2023