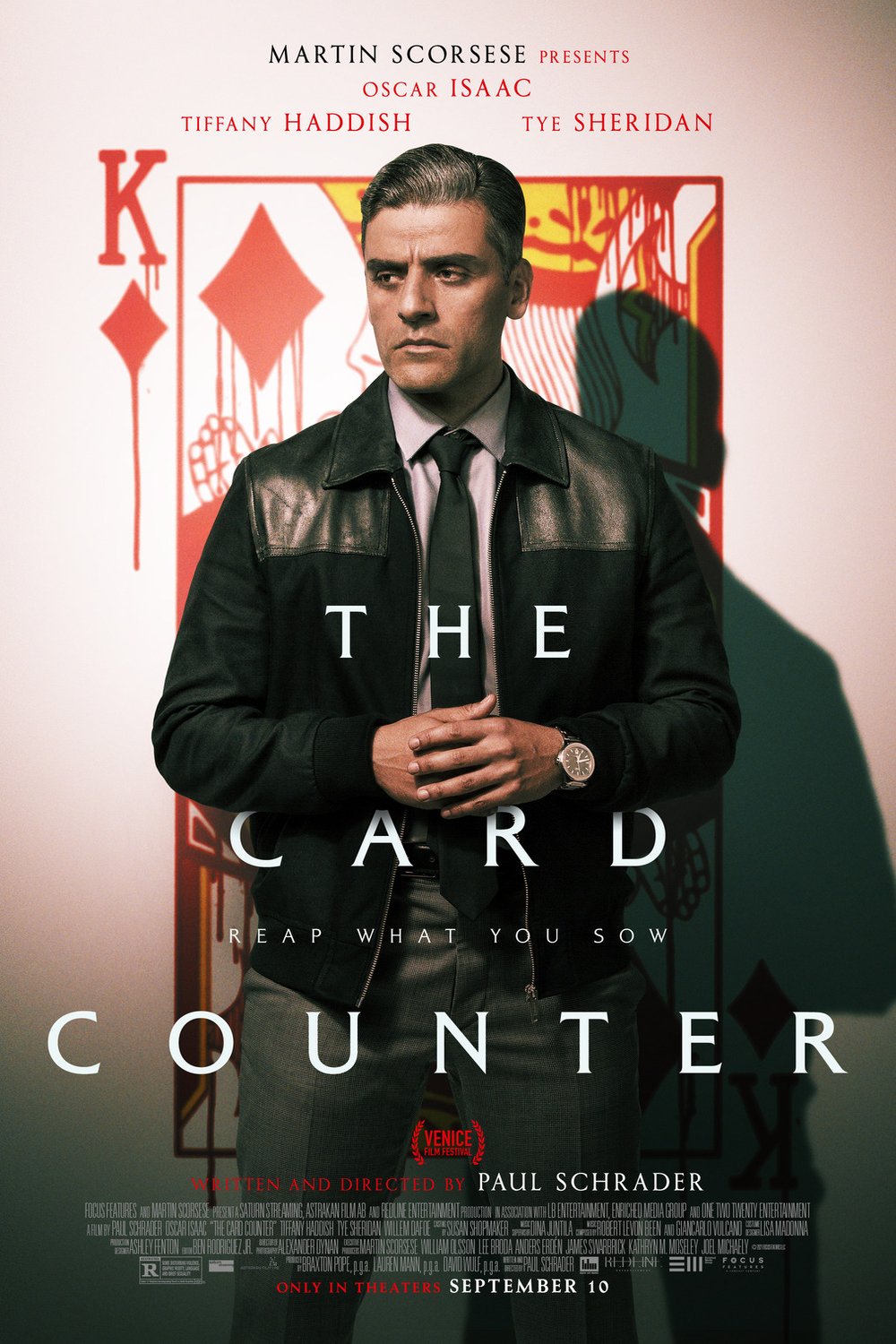

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Card Counter (2021) Film Review

The Card Counter

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

The system is not exact. It creates from cards a number. One that goes up, goes down. That number is then divided, split. As cards are dealt, probabilities change, the space of possibility constrained by each revelation. It is a way to narrow margins, to reverse the flow. To find, in the rough, diamonds.

It is not the only system.

Oscar Isaac is William Tell, though in various overtures to open him up that Tell is itself telling. He has a history. One that he himself is telling. A neat narrow script, ink into an exercise book, one line and margin ruled. A Lamy fountain pen, I think, from that distinctive wire curve of clip a Safari, probably Umbra. Black from black on black, roulette odds would get you 47.4% but European wheels weight green differently.

It starts with bass and baize. Neither immediately discernible, close and uncomfortable. Green and grime. The credits before the action, something old fashioned. Some of that Paul Schrader, writing, directing. Some of that tone. This is cool, Parker cool. Not Charlie cool, with the saxophone. The other Parker, Westlake's, Boorman's, Marvin's. Cool with a coldness, point black, payback. Cool as ice.

There is a set of card inflected crime movies into which this can be shuffled. Hard Eight, Croupier, The Cooler, Rounders, they are all about cards in the same way Blue Velvet is about fabric and Le Cercle Rouge is about geometry. The game is no-limit Texas Hold'em, of course, the televisable treat that fuelled the poker boom. Let us not worry about the rules, they will be explained, the rounds of escalation. Let us look at structure.

Two to start. At first it seems that those are Isaac and the young Cirk [sic], Tye Sheridan who's been the Ready Player One, a one-eyed king in the latter X-Men. These are called the "hole cards" though and there is a hole. Three more are community. Tiffany Haddish as La Linda, manager to a stable of players. In a single-sleeved dress she is made out like a bandit. There is Major Gordo, Willem Dafoe now straddling that skeletal line of age, a horseman in a polo shirt, sufficiently military and industrial to give anyone a complex. Cirk's mother, Judy, a small role for Amye Gousset but no less powerful for the frame of face-time.

Two more will come, but there's to be tension first. I give this as a reading for a film because it is not inscrutable but does allow it. Schrader's script is taut, indulging in times in insomniac driving that perhaps feels too much of the Taxi Driver, the Bringing Out The Dead. As a director and writer too he is fond of shadow, of contrast, of the stark. His cinematographer is Alexander Dynan and in combination they are better than good. After a swathe of murky mainstream mediocrity it was a delight to see colours, and though he has only four features this is his third with Schrader. It's a good match.

What seems like voiceover is narration of sorts, one that intermittently makes use of text upon the screen to add depth to text. There are moments where it seems a wrongfooting baton is passed but no spade is needed to dig what's going on. There's a black cat, a flag in a distressed arrangement, but there are symbols everywhere.

The soundtrack is almost exclusively by Warren Levon Been, member of band Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, named (naturally) for Brando's bikers from The Wild One. This is his first soundtrack, though his film connections are deeper. His father Michael provided songs for films including The Lost Boys, appeared as John, Apostle to Dafoe's Christ, Last Tempted. I don't know if it is entirely in the footsteps of band-members turned composers like Danny (Oingo Boingo) Elfman and Clint (Pop Will Eat Itself) Mansell and one must now say Jonny (Radiohead) Greenwood but it is at least as strong. Crispness of vision is met with depth of sound.

That vision changes. There are long, slow zooms, to long, slow speeches. There are moments of extreme fisheye, the edges of one of the film's prisons a distorted prism. The corridors wrap around us endlessly, enough to make one queasy, heartsick. In under two hours it could seem to drag but it is making clear the grind. Not just in the age of coffee, hand after hand until fingers are wearied, eyes are heavy. In a film all about ratios and balance it's almost entirely 4:3, odd on a cinema screen, odder still one expects on streaming platforms. A near-permanent boundary, a wall. Not the only one either.

The cost of things, that phrase, "what's the damage?". It is here. Isaac is in almost every frame, be it one of lights or mirrors or windows or wood. He has chemistry with everyone, Haddish, Sheridan, Dafoe, but it's in those moments alone even in company that he shines. It might have been the hair, the suit, the casino, but I was minded of Clooney's charisma and not just at play in the Oceans, the younger Clooney in that hand of Three Kings. An intensity, a cut, a cool. A coldness.

Tightly wrapped doesn't begin to cover it. Nor wound, nor wounded. The game is called Texas Hold'Em because it was, allegedly, invented there, but Texas is the state that joined America at least twice, and not without incident. The game is called No Limit but there are restrictions. There is only so much on the table. There is only so much that can be known. You can get more, but you need to borrow, and debts are difficult things. Morally, financially, physically, mentally. Though a lot is played close to the chest, The Card Counter is a treasure.

Reviewed on: 25 Nov 2021