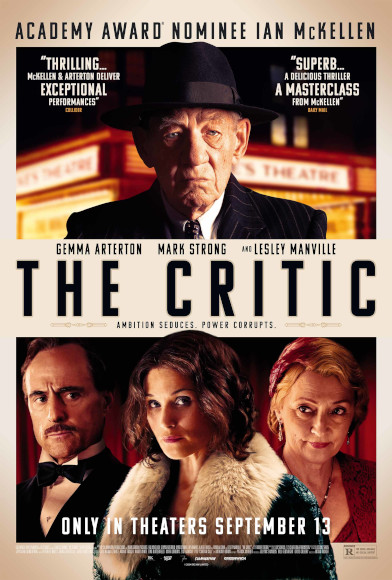

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Critic (2023) Film Review

The Critic

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There has always been a certain proportion of people whose primary interest in going to the theatre – or the cinema – is simply to gaze at somebody beautiful, regardless of the quality of that individual’s performances. It is due to the adulation of such people that Nina (Gemma Arterton) has found herself a place on the London stage. Even before Jimmy Erskine (Ian McKellen), the critic of the title, has delivered his withering appraisal of her work, it is difficult to believe that anyone ever perceived her as talented. Yet there is talent in there, Erskine assures her, in one of his more pitying or solicitous moments. She simply has to learn how to access it. She needs to learn how to be subtle.

One wishes that somebody had given that advice to writer Patrick Marber and director Anand Tucker.

With exquisite production design and cinematography, as well as a capable cast, The Critic, which is set in the mid-20th Century and adapted from Anthony Quinn’s novel Curtain Call, looks classy, and it’s easy to go into it with high expectations. Though a bit heavy-handed, the depiction of a long-esteemed newspaper facing financial pressure is one that any journalist today will relate to, and Nina’s bold decision, at the urging of her mother, to track down the man whose words she considers unfair is believable enough, though such incidents are thankfully rare (filmmakers take note: harassment will not get you extra stars). In its early stages, the film stands up pretty well. It’s when it reaches the blackmail stage of the story that it falters.

Erskine, you see, is fearful of losing his job, partly as a consequence of homophobia and partly due to his general disdain for other people’s rules. It so happens that his newspaper’s owner has a crush on Nina, whilst she in turn is desperate for favourable reviews, so he sees an easy route to solving his problems. Unfortunately for him, and rather disappointing in light of the number of similar schemes he must have seen presented onstage, he has misjudged both the human factor and the unlikely subplots which frequently flourish in stories like this, where everybody is already connected to everybody else.

The problem for viewers is that, though it’s presented as a grand emotional drama, the elements which are supposed to be most impactful feel alternately rushed and overblown. They struggle to compete with the emotional impact of a subplot which reminds viewers – and, in the case of younger ones, probably shows them for the first time – just how viciously gay men’s personal lives were policed at the time. The weight of this more widespread injustice, presented as it is, skews the story, so that McKellen ends up having to work hard to shake off the sympathy viewers might feel for Erskine early on, blunting his character arc.

For her part, Arterton is very effective, giving Nina a sweetness which never seems to be at odds with her ambition. She’s let down by a sudden requirement to be stupid towards the end, but in the meantime she’s very watchable, flexible with her own appearance so that we understand something of the effect she has on others but we also see the much messier and more interesting person underneath. Claire Finlay-Thompson, costuming, associates her with yellow, and Tucker uses a lot of yellow light in scenes focused on performance, so that it almost seems as if the artificial versions of herself that Nina presents have more significance than the real thing. Despite Erskine’s advice, nobody really wants her to be herself.

It’s still problematic. We’ve seen these characters before and their fates are obvious from the off. Opportunities to add depth at the narrative level are ignored in favour of complexity, which is not the same thing. There is a lot to admire, but there should have been a great deal more.

Reviewed on: 12 Sep 2024