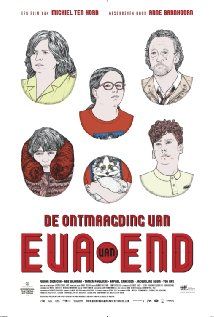

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Deflowering Of Eva Van End (2012) Film Review

For promotional and/or categorisation purposes, you might say The Deflowering Of Eva Van End (De Ontmaagding Van Eva Van End) resembles the work of Wes Anderson, in both its themes of familial dysfunctional and wryly eccentric aesthetic. That’s about as far as the comparison goes, however, as to take it further would be to risk a disservice to Anderson (if you’re a fan), or indeed to this film (if you’re not).

Working to a more palpably European register, Deflowering is a coming-of-age tale that highlights the peculiarities of intergenerational domestic frustration while not shying away from the uglier and cruder aspects of “growing up” – whatever your age. Deadpan on the one hand, it embraces exaggeration on the other.

Written by Anne Barnhoorn, the main source of director Michiel ten Horn’s debut feature might be Pasolini’s Teorema (1968). Into a comfortably complacent petty bourgeois family steps German exchange student Veit (Rafael Gareisen), a Christ-like prodigy whose pure smiles and good-Samaritan charms appear like some violent affront. The newcomer’s presence is as enigmatic and laced with friction as Terence Stamp’s was in the Pasolini work. Veit sparks differing levels of sexual curiosity in at least three members of the Van End family: in Etty (Jacqueline Blom), the sexually frustrated mother; in Erwin (Tomer Pawlicki), an acne-ridden soon-to-be-married store manager; and in Eva (Vivian Dierickx), a bespectacled adolescent who has to sit next to a wheelchair-using loner at school because she herself isn’t of any interest to anyone. Completing the family are perpetual adolescent grouch Manuel (Abe Dijkman) and bumbling patriarch Evert (Ton Kas in a standout performance).

Even if we overlook the curious implications of a blonde-haired blue-eyed German emancipating a middle-class Dutch family from its own anxieties, Deflowering has its problems. Dealing in broad stereotypes, the film wears thinner as it progresses. Though it goes to strange lengths to challenge and repel viewers – in, for instance, a scene involving the facial application of sperm as a cure for acne – it doesn’t give enough detail to the relationships on display. Though it might have shock value – whose deadpan delivery is part of the fun – some of the deeper unpleasantness here threatens to drag it down: racism, bullying, a rabbit’s snapped neck. No issue or incident should be off-limits in art, of course, but such inclusions here reveal an artistic talent that is derivative and/or short on confidence. Bullying scenes in particular are often a good gauge of a filmmaker’s prowess; sadly, as is often the case, the handling of those scenes in which Eva is the victim of hateful pranks never quite rings true, and the film suffers for it.

Reviewed on: 29 Sep 2013