Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Delinquents (2023) Film Review

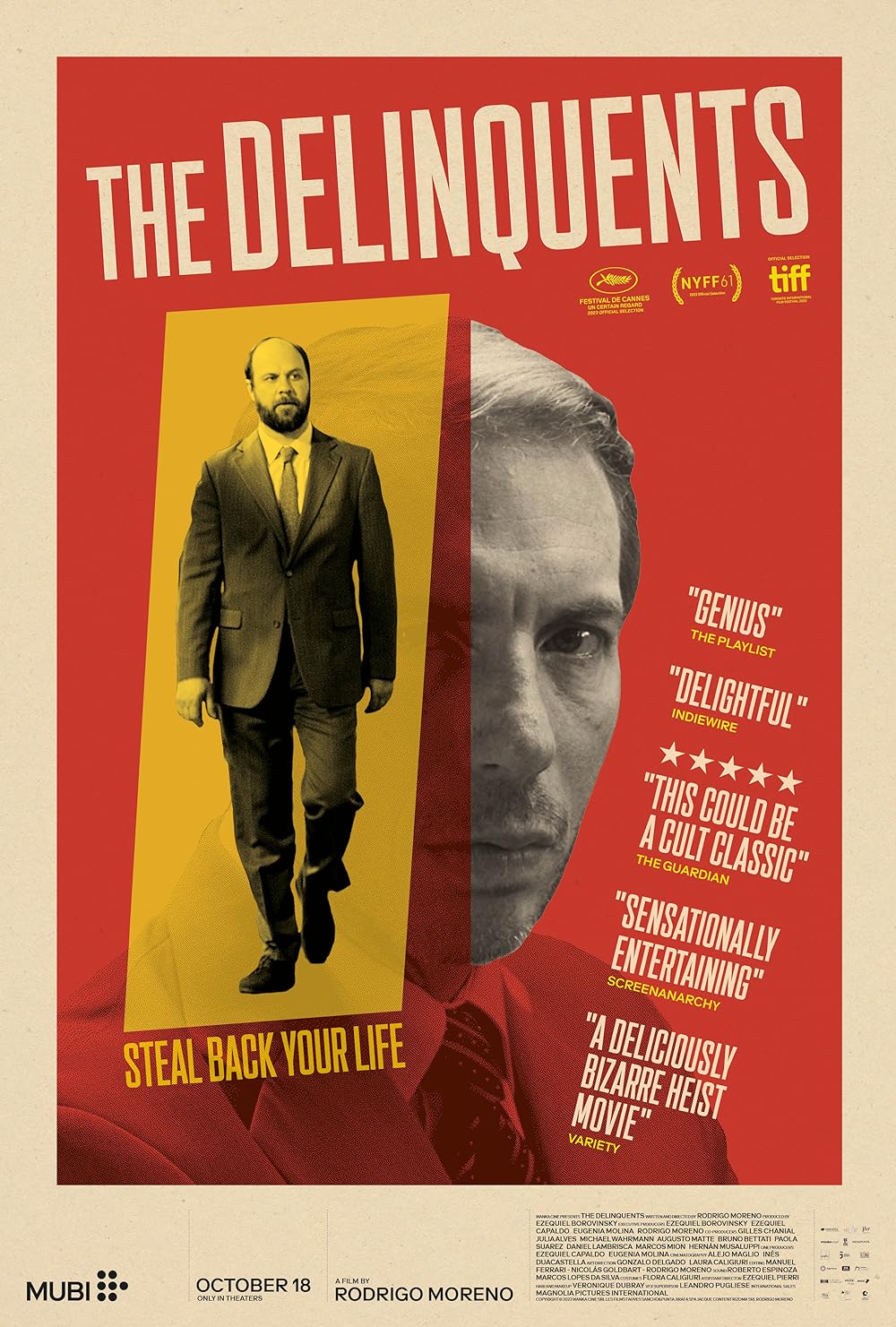

The Delinquents

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

It’s a simple matter of numbers, Morán (Daniel Eliás) explains. He has worked out, to the hour, how long it will take him, working in his tedious job as a bank clerk, to earn enough to retire and actually start living with the freedom he longs for. He has also worked out how long he will spend in prison if he simply steals that amount of money and then immediately confesses. In numerical terms, prison looks like a much better deal. He is not, as he sees it, a greedy man. He only steals as much as he would otherwise expect to earn, plus enough to pay a colleague to hide it.

That colleague is Román (Esteban Bigliardi), who has no idea about the scheme until he finds himself in the middle of it. What, then, are his options? It might seem like a sweet deal to be offered good money for very little work. If he says no, when Morán has already taken the money, he’ll be ruining his life. But he has moral qualms, and he’s worried about getting caught, and when fellow employees come to suspect him of involvement, his life becomes miserable. They can’t prove anything, and can’t sack him, but they can watch him continually and make him suffer in myriad petty ways. And whilst this is happening, Morán is discovering that prison is a far tougher place to be than he had imagined.

Is there any real freedom, or happiness, under capitalism? This is the question at the heart of Rodrigo Moreno’s film, Argentina’s 2024 Oscar submission, but the whole is rather more sophisticated than this may lead you to expect. Moreno isn’t shy about his use of symbolism. The two main characters reflect each other, as their names suggest. What this effects to disguise, however, is the degree to which their own thinking has been shaped by symbols and by the belief system which surrounds them. Most of the film is filtered through their shared perspectives. It is only at the end, when this breaks down, that it becomes apparent how little this has really permitted them to see.

It has often been said that the only true freedom is freedom of the mind. The tightly knit heist plot which takes up the first hour of this film invites us to set this aside, to find pleasure in what, though stylishly delivered, is ultimately familiar. In the second hour, we are offered a second form of temptation – the illusion of freedom which stems from associating with others who seem to possess it. Román falls in love with a happy-go-lucky young woman, Norma (Margarita Molfino), throwing away the life he thought he valued (and further restricting his wife’s life in the process) in order to be with her. Morán, meanwhile, finds refuge in books, engaging with the world in a new way yet remaining restricted to somebody else’s imagination (just as he and Román are trapped within Moreno’s narrative), his own daydreams just a fanciful retread of what he has briefly touched upon in the past.

Moreno has been criticised for failing to develop Norma as a character, but this would seem to misunderstand his intent. We really only see the young woman through others’ eyes, and the fact that she is treated as is she did not have a personality of her own leads directly to the collapse of the narrative in which both men had invested, during the film’s final hour. Norma comes to represent freedom in their eyes precisely because her life is a fantasy. We don’t need long in which to recognise that there is a real person behind that, not unknowable but unknown, with her own limitations and her own priorities. What freedom she has is not for others to take. If she has triumphed, broken out of the constraints of capitalist thinking, it has not been without effort or cost, and it has not come from a willingness to live her life on others’ terms.

In using this device to criticise the conventions of masculinity, especially where it aids and abets the capitalist project (another reason why the two men find it so hard to escape), Moreno implies that moving towards freedom must depend on a willingness to let them go. Most significantly, he suggests that it is necessary to stop prioritising security and strength, to accept the chaos of life and step out into it unencumbered. It is the wild, untamed countryside beyond the hills, not the beauty spots adjacent to the motorway where the men initially hide their loot and focus their dreams, which might have something real to offer. It is only in the space where the story ends that a character might truly escape.

Reviewed on: 06 Jan 2024