Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Exorcist (Director's Cut) (1973) Film Review

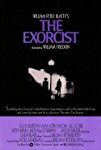

The Exorcist (Director's Cut)

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Widely believed to be the scariest film ever made, William Friedkin's seminal work acquired legendary status within just a few weeks of its release and if anything its reputation has only grown since. Adapted from William Peter Blatty's book, with roots in a real exorcism case from 1949, it has a simple story whose impact is rooted in its religious trappings and lurid special effects. Shocking at the time (and still reportedly traumatic for many people to watch), these haven't aged well and are not flattered by the high definition afforded by blu-ray. What that does give us, however, is the opportunity to see the fine detail in Friedkin's work and properly appreciate his composition.

Underlying all the director's work is a gift for finding the extraordinary hidden within the mundane, for showing situations escalating through a process that remains understandable to a point that seems insane. Here, too, it is in his representation of the ordinary that he is most astute - the really interesting part of the film, and the part that retains the most power, takes place before any major supernatural events. The social picture Friedkin gives us grounds what is to follow and also emphasises the vulnerability of the mother and daughter at its heart, doubly cut off by financial privilege and the absence of a male head of household. The mother, Chris (Ellen Burstyn), is clearly a capable person but her very rationality will work against her with what is to follow. As daughter Regan (Linda Blair) gradually loses her mind to demonic possession, Chris is forced to abandon something of her own sanity in order to seek an effective solution. If a doctor can't help then - even if it's only psychosomatic - could a priest?

This cut of the film contains sequences that were widely talked about upon release but were missing from the original, most notably the spider walk scene, where Regan crawls head first down the stairs on her back - at the time when it was shot the effects just weren't good enough but CGI has since polished it up nicely. It's important because of its positioning in the film, marking the shift between out of character behaviours that could signify psychiatric illness and the sense of there being something so wrong as to be almost uninterpretable. That it happens in a brightly lit suburban home adds to its power but the real horror is, of course, rooted in Chris' fear for her child rather than in a fear of what that child might do to others. Despite the mutterings of the priests the latter prospect isn't really developed, but it is effectively hinted at by a scene in which Chris is herself assaulted and then trapped in Regan's bedroom, her instinct to survive briefly overriding everything else.

It's unfortunate that the first aberrant behaviour we witness is swearing, shocking in its time but now lacking the same cultural relevance, especially when delivered in a voice not unlike that of a popular MTV cartoon character. By contrast, a scene in which Regan makes sexual suggestions to adults retains its power to disturb but also remains problematic in its association of precocious female sexuality with malignity. At 12, Regan was a helpless child in 1973; in today's world we instinctively grant her more agency so the territory between self and demon becomes more obscure. In some ways this could strengthen the film by helping it retain its ambiguity for longer, but the schlocky effects undermine this, and they're harder to accept in a film famous for its scariness than in something playful like The Evil Dead, which consequently has more staying power.

So does The Exorcist still deliver when it comes to terror? Yes and no. There is a persistent weightiness to it, largely thanks to the presence of Max Von Sydow as the ageing priest haunted by cases of possession he has seen in the past. People whose personal religious beliefs incorporate the possibility of possession, or simply the fear of loss of an immortal soul, will find that it presses buttons effectively. There's also a body horror aspect to the film that will deeply disturb some viewers, though it's mild compared to much of what we've seen in recent years, especially in Japanese cinema.

More effective than simple scares is the underlying psychological horror of the film which, especially in the early stages, doesn't depend on the supernatural - Chris' fear that her daughter may be so severely mentally ill that she needs to spend her life in an institution is powerful, with Burstyn delivering a strong performance. Blair, for her part, shifts very effectively between the furious, energetic aggression of the possessed Regan and a very naturalistic childish openness. The cheery young local priest played by Jason Miller gets the biggest character arc, with his transformation mirroring the viewer's journey and hinting, through backstory, at some of the day to day horrors we habitually minimise. Von Sydow, meanwhile, gives us a character straight out of Lovecraft, a man who has seen too much, out of place among the others but, like the divided Regan, using contrast to disorientate.

Taken as a whole, The Exorcist is not the icon of terror it once was, but it's still a solid film with a lot to recommend it, and a must for those with an interest in horror history.

Reviewed on: 27 Aug 2014