Eye For Film >> Movies >> The King Of Laughter (2021) Film Review

The King Of Laughter

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There’s a pastoral scene about halfway through Mario Martone’s indulgent portrait of Italian theatrical legend Eduardo Scarpetta which throws everything else into sharp relief. In it, we see one of the playwright’s youngest children, Peppino (Salvatore Battista) running through the farmyard at the place where he is being temporarily fostered, chasing a playful young lamb. Here there are soft green hills, the sun is warm, the buildings are humble but welcoming. Later, Peppino will ask for permission to share his bed with the lamb. he doesn’t want to leave. He doesn’t want to go back to that ugly house in the city.

That ugly house is known as the Scarpetta palace, a lavishly furnished, expansive mansion where the playwright (played by Toni Servillo) lives with his wife and mistresses and some of his numerous offspring. it’s a place where the women and girls are magnificently dressed and drift around idly, caught between bursts of passion, subdued languor and vague worry about their future financial security, whilst the young men and boys are largely ignored, hustled out of sight or stacked up against the walls like so many spare parts. Peppino hovers in doorways, perpetually unhappy. Despite his tender age, he already understands that everything revolves around his father’s ego, and that the only way to please him is to go onto the stage and perform in his plays, speak lines he wrote, follow his instructions exactly, become an extension of his will.

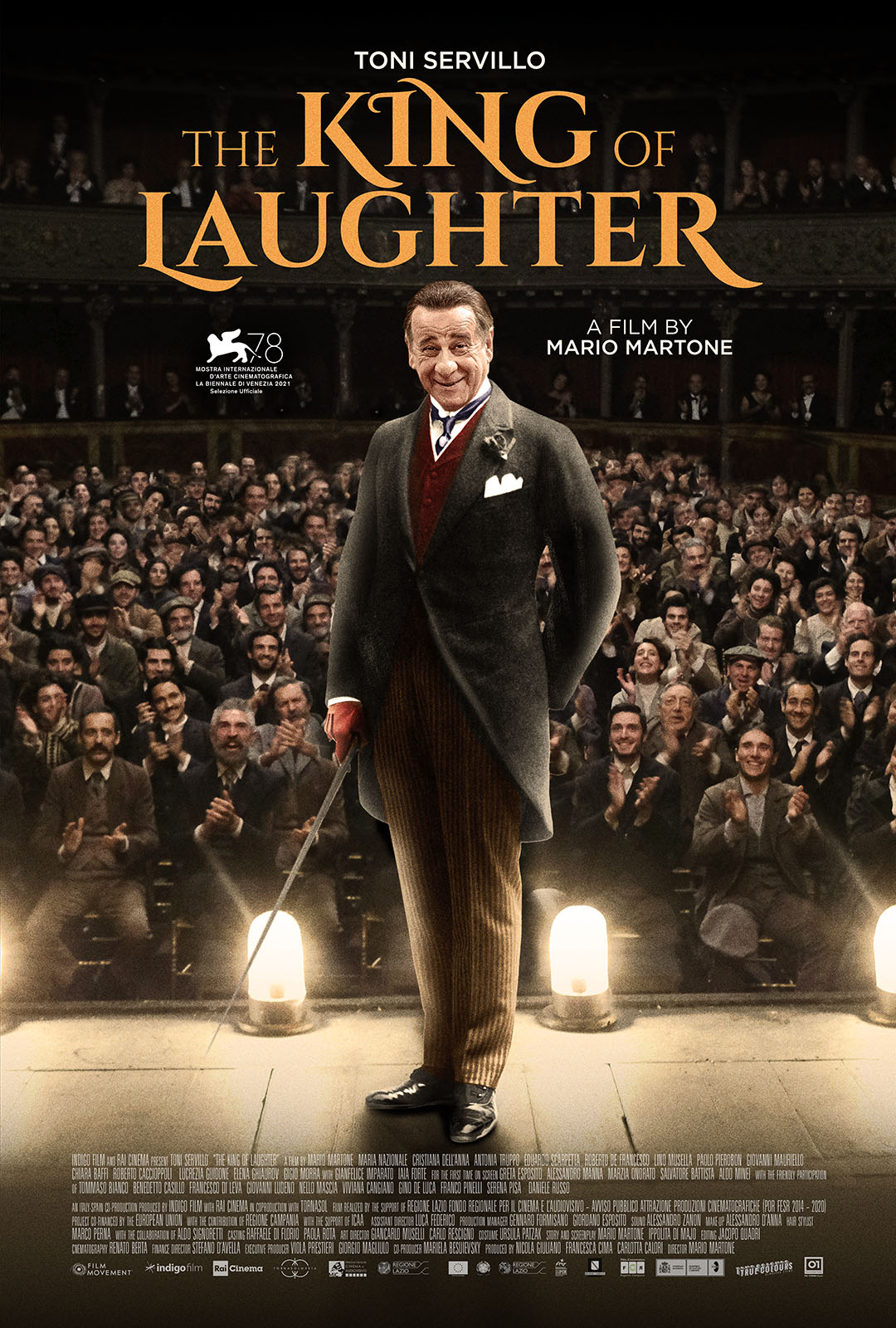

The contrast between this largely benevolent but still tyrannical private existence and the light, playful image which Scarpetta projects to the masses forms the bedrock of the film, even as it purports to focus on something else – a trial over the distinction between parody and plagiarism which would ultimately enable Scarpetta, here and in real lifem to present himself as a hero, a defender of free speech and a man of the people. The latter conceit hinges on the age-old conflict between popular entertainment and high art, with Scarpetta beloved by many ordinary theatre-goers because of his amiable buffoon alter-eho, Felice Siociammocca, even as rivals rage that his dominance has robbed them of the chance to address more serious subjects or encourage more sophisticated intellectual engagement.

Photographic portraits of Siociammocca line the walls of the house where Scarpetta enjoys luxuries which the common people could not imagine. Though he’s worried about the security of it all, he does his best to hide that from his family, and doesn’t let it stop him making babies. He seems confident that if all else fails he can fall back on his wits, but is that realistic, or a product of narcissism? Viewers are caught in an awkward position where they might wish, for his family’s sake, that someone would cut him down to size – and yet, for his family’s sake, he has to maintain his success.

A descendant of the family, Eduardo Scarpetta, stars in the film as the playwright’s frustrated eldest son, Vincenzo. This isn’t just a cute bit of casting – it’s a reminder that Scarpetta’s family has remained active in the Neapolitan theatrical scene across three centuries. As such, one might also trace aspects of the film’s own style to their influence, Martone being a Neapolitan too. This film is every bit as pompous and overblown as Scarpetta’s creations, never using one word where six will do, overwhelming viewers with its parade of fantastic costumes, richly appointed sets and sumptuous meals, its central character turning every conversation into an occasion for the making of speeches. There’s a knowingness to this – it seems, itself, like a form of play – but it will be too much for some viewers to stomach.

Servillo, of course, has spent much of the latter part of his career playing narcissistic characters, and he’s perfectly cast here. Although all the visual and thematic noise leaves him with limited room to manoeuvre, he manages to find small moments in which to express a deeper emotional complexity, even a fragility, which makes Scarpetta much more interesting than he might have been.

Also worth noting here is the presence of young Alessandro Massa, who delivers an engaging turn as the son to whom Scarpetta gave his first name (if not his last). In 2019, Martone released The Mayor Of Rione Sanità, an adaptation of a play by Eduardo De Filippo, the playwright whom the young Eduardo would grow up to become. There is a comparative spareness and freshness about De Filippo’s work which might have been welcome here. The self-conscious interjection of that single scene of pastoral romance acknowledges the established conventions of Italian cinema and makes the excesses of The King Of Laughter feel wholly deliberate, an experiment in exaggeration to the point of absurdity – yet as the film’s Italian title reminds us, we are not the ones laughing here.

Reviewed on: 25 Nov 2022