Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Matrix Resurrections (2021) Film Review

The Matrix Resurrections

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

When I got home I looked out my copy of Baudrillard's Simulacra And Simulation. I pulled it from an IKEA Expedit bookcase, those serried cubes now replaced in the catalogue by the more narrowly framed Kallax. In 1999 Thomas Anderson pulled his copy from a stack of papers in a metal shelf, folded steel legs perforated for shelves untaken.

The slim volume was stuck between a signed copy of a book about Bitcoin written by a friend of mine and two copies of Hideyuki Oka's How To Wrap Five Eggs. The thick green, faux-leather bound copy with its bookending capitals and heavy ampersand was stacked between papers and printouts. I turned to page 121 of The University of Michigan Press translation (Sheila Farrier Glaser, 1994, from Jean himself in 1981). Neo turned to a page where the hollowed book contained hand-labelled storage media, TDK MiniDiscs. That is where one would find 'Simulacra and Science Fiction'. That is where one would find 'On Nihilism'.

The first contains the sentence "Well, from one order of simulacra to another, the tendency is to reabsorption of this distance, of this gap that leaves room for an ideal or critical projection". The second contains the sentence "What new scene can unfold, where nothing and death could be replayed as a challenge, as a stake".

Both are here.

'What is the Matrix?', asks the first film, and it answered it, after a fashion. 'What does the Matrix mean?', asks the fourth film, and it will answer it, after a fashion. I don't know that spoilers matter when a film considers the wall a floor whether it be fourth or not, but the nature of its revelations and explanations is such that it deserves to allow audiences to whom the first meant something and audiences to whom the first meant nothing to follow afresh.

There's a rabbit. More than one, in fact, indeed, recursively. Even at the beginning we're told this is "old code", that it "feels like a trap". Things are happening in the shadows and puddles that hint at meaning behind, between. Though it rarely comes up, the thin layer of silver behind the glass that makes a mirror a mirror is called the tain. Here legacy stains reflection, stains contain the tain.

I enjoyed it. More, I must admit, than I expected to, after the same tautness and economy that made Bound so efficient became the rows and columns of The Matrix, then the spread sheets of expansion, contracts to perform. The level of metatextuality includes a reference within the film to a Warner Brothers induced remake. That's the Warner Brothers that was bought by walled-garden ISP AOL in 2000, by the differently telecom-predatory AT&T 18 years later, and on either side changed that WB logo so it was made up of more than those two characters.

The Matrix exists, of course, here as a videogame within the world of the film, one with merchandise that comes from the film outside of the world. That's a McFarlane Series Two Trinity Falls figure, intact with reflective catsuit and two mini-Uzis endlessly spitting dual moulded plastic bullets into a cubicle sky. It is not the only callback, indeed so numerous are they that at times one might wonder if they were held in a queue because they were important to us. Also held back is a new project, over-budget, known only as binary. Thomas is apparently a successful man, with a partner to take care of the business. Won over by zeroes. Waiting for a fall.

There are weaknesses. Moments where we see pieces of the old films, memories, in others that projection from page 121 on new players and old, on an old stage that's new. The difference in grade is greater than age but these are different forms of the real, different degrees of digital, different passes at the parallel. Some of the fighting is choppier than one might like, at least two-sided in a three-dimensional space it just about manages to keep relative positions clear but telegraphs some and obfuscates others. It relies, absolutely, upon nostalgia, but not just for The Matrix.

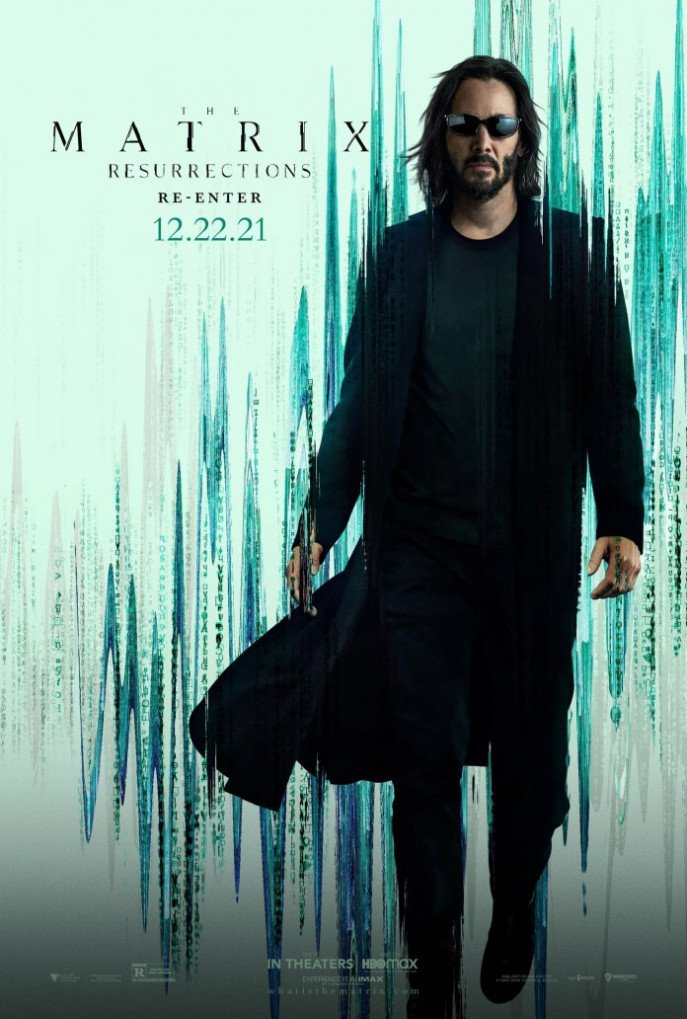

Time has passed. Keanu Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss are not who they see in the mirror, but even with Neil Patrick Harris' help it defies initial analysis. There's a firm called Deus Machina at which Thomas Anderson is a John Carmack like figure, but it's Epic's Unreal engine that gets a tech credit rather than the superego of id. Other characters return in new and the same ways, and through it walks a cat that might be from Yorkshire or Derbyshire so proximate is it to Cheshire. New characters too - Jessica Henwick adds to a CV that is beginning to rival that of Karl Urban for always being able to find a space in autograph alley at any science fiction adjacent convention.

In some places the density of design and creature recalls the Wachowski's indulgences in Jupiter Ascending, in others there is perhaps too much glee in metatextuality. This certainly true of the scene all the way at the end of the credits, Easter Eggs as much a gift of the bunny as the labours of a Ready Player One. Co-written by director Lana Wachowski and David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas) and Aleksandar Hemon (who worked with the Wachowski sisters on TV series Sense8, there are nods even in makeup and costume design to some of their work. Johnny Klimek and Tom Tykwer worked on those as well, and elements of Don Davis' scores for the first three reappear. There's a bit of the Propellorheads' Spybreak!, a musical project whose ties to film also include James Bond, the secret agent without a secret identity. One of the inverses is perhaps an identity without agency, or any agent without any identity. Both are here.

Elsewhere, musically, culturally, Jefferson Airplane's White Rabbit is from 1966, based on a book then already 101 years old. There's a quote from Don DeLillo's debut Americana (a subject upon which M.Baudrillard has pondered), it too about a modern man whose artistic endeavours have changed them. It's 100 years younger than Through The Looking Glass, revised 18 years after that. Stories are not just there, but in the retelling. Both, too, are here.

I enjoyed it, and I must admit more than I expected it to. Some of the newer effects are not perfect in their execution but their intent is clear and within them so is their action. If ever a film series deserved credit for operating within constraint... There is reabsorption here of what made the first one work, a novelty, a ludic distance, a film for people who might not say ludonarrative dissonance but have felt it. It's online enough that character names provoke reactions, even laughter that might ring false. It's grounded enough that there's a spark when hands touch.

There's a cover version near the end, that's the same, but different, and differently the same. We've seen a lot of works devouring their own tales and with different levels of success. The odd Rogue One achieves something new from within something old, and Resurrections might be it. I know this, among many other things - when I finished watching it I was already looking forward to seeing it again, again.

Reviewed on: 21 Dec 2021