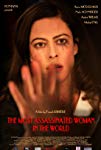

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Most Assassinated Woman In The World (2018) Film Review

The Most Assassinated Woman In The World

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

There is a contemporary estimate that Paula Maxa yelled "They are killing me!" 1,263 times from the stage of the Grand Guignol, a number achieved by the calculations of critic Camillo Antona-Traversi. At Antona-Traversi there is a monastery, founded after a miraculous escape from threatening boars. I mention this to juxtapose the lofty and the base, pigs of various stripes and perils of various types. Shades of Hannibal Lektor, but reader beware - there are old old arguments here, about media and murder, consumption and killers, writ large and loud and lush.

One of a number of Netflix productions shown at 2018's Edinburgh International Film Festival, this is a nest of tricks and trades - there is a murder plot, a journalist, misdirection and threats, artifacts of films past to create a sense of times gone by. There's a mirror and postcard trick that recalls magic lanterns, a kris-like dagger in a startling stabbing substitution, a sumptuous set of credits at the start that recall the studio titles of the studio era, somewhere between the then of the theatre on rue Chaptal and the digital-era behemoth launched by myriad mirrored mailers. There are various details that speak to care and attention in period detail, others that raised other questions - plane tickets among them. It's often a measure of audience engagement that questions of detail become pressing, but I wondered about one route, worried more about other things.

Those start with tone. There are some good moments, some striking ones, but electric guitars are not, perhaps, the only distortions. Though Anna Mouglalis' Maxa is the heart (bloodied, beating) of the film, the camera at points literally spiralling around her in a sumptuous bed, a seemingly infinite plane of satin, though we've characters who are women discussing things that are not men, the extent to which I can credit a film for feminism is inversely proportionate to the number of times it credits actresses as "murdered prostitute". Some of this might be translation - there are songs without subtitles, the film is not only French but period, the past is a foreign country, the world may be a stage and the stage is a world that's all its own - but I was still uneasy.

We've got journalism of sensation - and the giallo comparison is right there but I will resist the alliterative 'gutter' or the similarly synaesthetically synonymic concolourous 'giallo' - and this is similarly dependent on the old kroovy, blood flowing from and to and within, sex and death.

There are references to old cinema - Doctor X makes an appearance - and moral panics that have been replicated with comics and consoles and so on. Those parallels are perhaps indicative, as duals and doubles and doppelgängers abound. Reflections and redirections, and moments of mystery. There was a moment that made me wonder if a singer had been substituted or if it was an act of improbably basement club geometry, and that was before ritual recollections of older trauma, bad times at beach-side become littoral meta-text. A rebroadcast at the stage door is full of details of appreciation and to appreciate, but there are some other stories being told on top of these stories. Somewhere in here is a true story, but differential recollections, gaslighting by any other name, all the usual suspects of storytelling about storytelling. Neuroses by another other name would smell as sweet.

There's some excellent effects work to recreate stage-blood and mummery, some real moments of tension and fright, but with four credited writers I wonder if it's trying in too many directions. I's Franck Ribiere's début fiction feature; he directs, shares writing credits, moving on from a CV heavy with production credits. Channel 4 education TV alums James Charkow and David Murdoch are credited with the original idea, frequent Ribiere collaborator Vérane Frédiani is the fourth writing credit. One suspects an idea born in one place and executed in another, which comes dangerously close to the plot of the film.

It's too fictive to be a historical document, perhaps too intent on showing us how clever it is rather than just being clever. The air of unreality is not always intentional. Through the lens of history but also subsequent cinema it's hard not to read into maps with connecting strings, borrowed lipsticks and deliberate attempts to create emotional trauma to elicit performance, and the mixture of the allusory and the illusory is perhaps less one of vigorous variety than vile viscosity. It's never quite that one feels complicit, and if I am charitable it may be that it intends audiences to feel uncomfortable, but I am not convinced. One of the elements I recall most fondly is a cloud that looked a bit like a cat, and I don't think that was necessarily the film-makers' intention.It's gripping in places, good in others, but it lazes in others, drags. As a stage for talent it certainly serves as showcase, but those watching it should tread carefully lest they end up bored.

Reviewed on: 22 Jul 2018