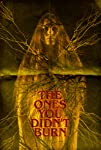

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Ones You Didn't Burn (2022) Film Review

The Ones You Didn't Burn

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

A slow-burning meditation on land, family and betrayal, Elise Finnerty’s début feature is narratively slight but visually stunning, more of a poem than a story. It follows brother and sister Nathan (Nathan Wallace) and Mirra (Jenna Sander) as they return to the remote farm where they grew up. Their father has died – by drowning himself, it emerges – and they have come into their inheritance. Mirra would like to make something of it but is concerned about the effect it might have on Nathan, who has been sober for some time but remains precarious, always turning to her for money and unable to find any direction in life.

Even allowing for the difficulties caused by Nathan’s addiction, the relationship between these two siblings is an odd one, full of secrets and unspoken things which may have their roots in the same unhappy childhood which led to them moving away. They don’t engage in much direct discussion of their father but a good deal is conveyed through body language and exchanged looks. Conversations with others in the area hint at a deeply problematic legacy, and even suggest that he might have got the land by fraud. There is talk of it having been cursed.

The land is a constant presence in the film, lying low but vast, making its human inhabitants seems scarcely more substantial than the tall blades of grass troubled by the wind. Hemmed in by the sea which claimed his father, Nathan is tormented by nightmares in which something only half-human crawls out of it, threatening and alluring at the same time. The sky hangs heavy overhead, as if pressing him down against sand and soil. Its dark blues and greys against the green and yellow of the land seem to speak of bruises, of old injuries.

The film is full of beautiful women – not least its director – who seems at ease with the land and its legacy in a way that Nathan never can be, though he watches as his sister is drawn to them. Their sexuality, though not conventionally aggressive, is presented like a threat. Under this pressure, he collapses inward, soon returning to his old habits, crying out for help from a sister who is tired of being expected to save him from himself. Meanwhile, going through the boxes of old possessions in the farmhouse, he becomes convinced that something sinister is afoot, that the women are more than they seem. Is this true? Is it a manifestation of mental illness? Finnerty carefully preserves this ambiguity to the point where we are left to wonder if it really matters: the outcome might easily be the same.

With a huge, raggedy string score by Daniel Reguera, the film is big on atmosphere and never gives one the sense that its protagonists wield much control over their destinies. Finnerty knows what she can do well and sticks to it. The result signals that she’s a new talent worthy of serious attention, even if it feels, in many ways, more like a short than a feature. The imagery will linger in your mind far longer than the rest.

Reviewed on: 02 Sep 2022