Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Red Scarf (2020) Film Review

The Red Scarf

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

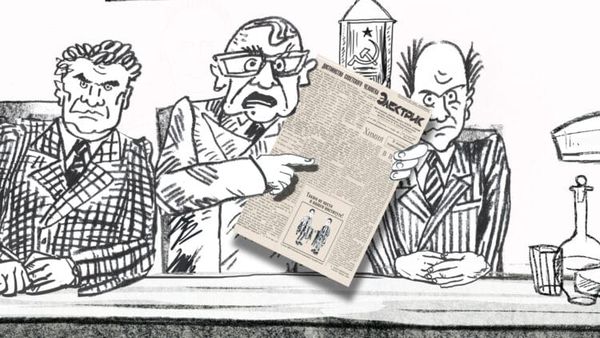

Blending family photos, animation, archive footage, his own films and a sharp wit, Russian director Peter Mostovoy takes us on a journey through his childhood and early years in filmmaking before he quit his homeland permanently for Israel in the Nineties. There's a sprightly feel to this documentary journey and the hour in Mostovoy's company flies by.

Though the observations he makes and stories he tells are personal, they also paint a vivid portrait of the totalitarian regime of Russia at the time, showing how Mostovoy fell foul of those who wanted to control his work, almost by accident, while also facing ingrained prejudice because he was Jewish.

His memories are colourful and evocative, whether he is talking about his family's cramped home, where he slept on the dining table, or recalling an unexpected childhood invite to a party. It's in his teenage years where things become most interesting, however, as he heads to university to study physics - a subject that was a considerable distance away from his true love, photography.

They're also a far cry from politics, but he finds himself falling foul of the regime after all, following an ill-fated attempt by him and a friend to advertise something for sale at a market. That something so hastily thought of could have such repercussions - an "untrustworthy" tag that would follow him - only emphasises the absurdity of authorities determined to clamp down on western "propaganda". The country's thinly veiled antisemitism of the period is also revealed, not just in the fact that "only one Jew" would be accepted on some courses but in the aftermath of the market incident, when his non-Jewish "partner-in-crime" is given an opportunity to blame him entirely, even though it was an offer he did not take up.

As a documentarian, it becomes apparent that Mostovoy has always been innovative, turning the camera on viewers of a Hermitage painting in Look At The Face and garnering success that would again attract the attention of authorities keen to shape the idea for their own propaganda purposes. Meanwhile, his follow up about cafe society was considered so off-message that all copies were ordered to be destroyed by the studio - although the filmmaker secretly kept a copy. Mostovoy recounts the events with a lightness that belies the prejudice and attempted manipulation he faced, but which only helps to emphasise the hypocrisy of a society riddled with the very problems it declared erased by Communism. This is both an enjoyable personal memoir and a valuable snapshot of pre-perestroika Russia, that would make an excellent double-bill with Ilze Burkovska Jacobsen consideration of Soviet propaganda, My Favourite War.

Reviewed on: 29 Jun 2021