Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Returned (2020) Film Review

The Returned

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There were riots in Buenos Aires in 1919, the year that Eva Peron was born. Communists predicted a workers' uprising. The elite were willing to do anything to hold onto power. Neither paid much attention to the indigenous peoples of the country, most of whom had been massacred or driven to the farthest reaches of the plains or jungles. Of the ethic European population, only those farming in such remote regions came into contact with them. Yet as their numbers dwindled, their European contacts finally began to recognise the full horror of what they had done, and in the shadow of guilt, fear and superstition began to grow.

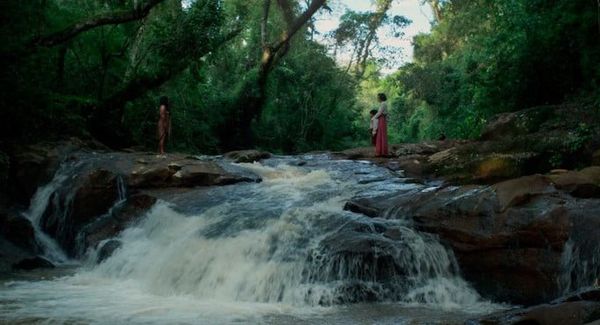

Laura Casabé made a splash in 2016 with the striking art scene horror/mystery Benevidez's Case. Now she's back with an equally probing drama set in 1919. It centres on Julia (María Soldi), whose husband Mariano (Alberto Ajaka) runs a maté plantation on the edge of the jungle. Supported by servants including the redoubtable Guarani woman Kerana (Lali Gonzalez), she's not expected to do much in the way of work. Her role is to please her husband and to give him heirs, but the latter is a task she cannot accomplish. After multiple miscarriages, she is devastated to have her latest pregnancy result in a stillbirth. Desperate - and ignoring Kerana's frantic pleas to reconsider - she visits a sacred waterfall and prays to the Guarani deity Iguazú, the mother of day and night, to give her child life. Iguazú obliges - but as with most such pacts, there is a heavy price to pay.

Based on Casabé's short film La Vuelta Del Malón, The Returned is another puzzle of a film, unfolding in non-chronological order and repeating some sequences from different viewpoints to reveal new layers of information and invite fresh understanding. It's heavily focused on the underlying conflict between the whites and the Guarani, still potent when cloaked in the pretence of civility, but this is complicated by their mutual powerlessness against the forces of nature. The word 'iguazú' simply means water, and seems to reflect that indefatigable presence, brilliant captured by Santiago Fumagalli's sound design and Leonardo Martinelli’s sweeping score. The further the Europeans press into the jungle, the closer they get to the darkness at its heart.

Fixated on the survival of her child, Julia has a sort of purity which brings her, despite her awful deed, closer to an understanding of the world around her - a world in which the European values of logic, reason and Christian ritual mean little. Like so many city-born men confronted with places that are truly wild, Mariano is losing his mind, descending into a way of thinking that is centred on violence. A certain sympathy develops between the women in their fear of this. Though he struggles to push himself to the centre of the narrative, Mariano is forced to confront his own insignificance and the real root of his (and his new nation's) terror: the awareness that the brutalised local people might one day rise up and take revenge.

In these lush surroundings, paranoid minds can never rest. There are shadows everywhere, shapes moving on the fringes of one's vision, and it's easy to suspect that one is being watched. A potent strain of Catholicism might suggest the omnipresent gaze of the divine but there's a sense that Mariano's god has little jurisdiction where the trees grow thick, where the water tumbles down unceasingly. Casabé captures a wold far removed from the one he and Julia have known, along with a growing awareness among the settlers that do what they may, this place will never resemble the quiet hills and peaceful villages of Spain. Layering fragments of story like the thick green leaves around us, the director, increasingly confident of her command, gradually obscures everything else.

Reviewed on: 23 Oct 2020